What is Bidenomics?

Is anyone telling the truth?

Image Description: Joe Biden smiling and making it rain with a stack of cash.

Image Description: Joe Biden smiling and making it rain with a stack of cash.

What is Bidenomics?

Whatever it is, the Republicans in Congress say Bidenomics is terrible, a conservative pundit literally called Biden a “sadist,” and establishment mouthpieces think Biden is FDR.

Much of what the right is saying is true. Prices went up, and even though inflation is cooling, prices never came down while wage growth has simultaneously begun to slow. That’s an undeniable gap that has pressured middle and lower income earners.

One point to the right.

Then again, inflation is indeed cooling and it just so happens that it was on the heels of the Inflation Reduction Act. Are they correlated? Hardly. But it’s a convenient narrative. What’s real is low unemployment. Employment is an unassailable metric that will be a challenge to the Republicans during the election because most Americans are loath to make changes when they have jobs. That being said, this is a way more complicated economy than the previous five or six decades.

So…one point to the left?

Maybe half a point. The real story of Bidenomics is found in the data. The election will be determined by how Americans interpret the data and who does a better job selling it because Bidenomics, in my estimation, represents the closing chapter of neoliberalism and signifies a shift to the next political era.

Anyone who claims to know what the holy hell is happening in this economy right now is lying to you. The White House is trying to own the economic narrative ahead of the upcoming election for one simple reason: it’s still the economy, stupid. On that, the pundit class has it right. There is one constant in American politics, and perhaps in all democratic exercises: how the electorate feels financially at the moment the levers are pulled determines which direction they’re pulled.

Both sides have data, charts and graphs that tell part of the story, but only the American people can really tell you how they feel. And they’ll have an opportunity to do just that, even if one of the candidates is behind bars.

Just as stagflation threw a monkey wrench into the world of economics and turned politics on its head in the 1970s, I guarantee this post-pandemic period will be studied for decades to come. So, you can take some comfort in that you’re living through interesting times.

I know numbers and charts can be pretty dry, so I’ll try to keep this more engaging to better contextualize the data. And we’ll hit all the high notes. Money supply and the Federal Reserve, the ongoing tension between Keynesian fiscal and Friedman free market responses to the pandemic, high level macro indicators that are upside down and some real on-the-ground numbers that impact our daily lives; and, hopefully, we’ll draw a couple of rational conclusions about the state of the economy, whether Bidenomics is actually a thing and whether it will ultimately vindicate the administration or bite it in the ass.

Chapter One: What we can learn from the “China Miracle.”

Before we talk about U.S. economic policy, let’s look across the globe for a minute to offer a comparison and a warning. Depending upon your media source, China is either poised to resume its staggering pre-pandemic growth (Jeffrey Sachs) or it’s about to crash and burn (Adam Tooze). But, for the most part, the financial mainstream media is hinting at potential catastrophe, so it’s worth digging in for reasons I’ll explain in a moment.

One of the more prominent articles making the rounds right now is from Adam Posen in Foreign Affairs. I don’t have much of a history with Posen, but I know he’s respected and he recently appeared on the David McWilliams podcast. From the article:

“What has become clear is that the first quarter of 2020, which saw the onset of COVID, was a point of no return for Chinese economic behavior, which began shifting in 2015, when the state extended its control: since then, bank deposits as a share of GDP have risen by an enormous 50 percent and are staying at that high level. Private-sector consumption of durable goods is down by around a third versus early 2015, continuing to decline since reopening rather than reflecting pent-up demand. Private investment is even weaker, down by a historic two-thirds since the first quarter of 2015, including a decrease of 25 percent since the pandemic started. And both these key forms of private-sector investment continue to trend still further downward.”

The author posits the view that China’s brand of autocracy—similar to Putin, Chávez and now Maduro, or any other authoritarian regime—has intervened far too much in the economy. He reasons that the increase in household savings and decline in private investment, both of which are real, are the result of President Xi’s arbitrary authoritarian policies rather than the end of an economic growth cycle.

The Associated Press recently reported a similar phenomenon, claiming that foreign companies are increasingly uneasy about Chinese government intervention and push to become more self-reliant.

These analyses are fair, but perhaps slightly overblown. The most persistent problem within China is the downward pull of a collapsing real estate market. Certain pundits would like us to believe that President Xi Jinping is becoming unhinged and crushing free enterprise and foreign investment; a sign that he’s leaning back into the more authoritarian days of the Communist Party. But that overlooks the fact that China has been far more ruthless even during periods of remarkable economic development. And I have a hunch that it plays into ulterior motive narratives designed to turn us against one of our most significant economic allies.

Back to authoritarianism. After Deng Xiaoping, who is widely credited with planting the seeds for China’s economic renaissance, stepped down in the wake of the Tiananmen Square protests, reformer Jiang Zemin guided the nation through the 1990s, averaging a 10% growth rate per year. Did he do it by being less tough? To the contrary, he went on a relentless campaign to jail dissidents, journalists and activists. But he opened the markets and eventually helped China secure a place in the World Trade Organization, an important milestone that we’ve covered before.

Point being, China’s economy isn’t falling apart because Xi Jinping suddenly became a ruthless dictator. It’s because China adopted the newly perverted form of U.S. capitalism in the 1990s. Over the 35 years following World War Two, the United States grew at historic rates. And then it hit the wall and overcorrected to favor corporate America and push down the middle class. In the 35 years since Tiananmen Square, China followed a similar trajectory, which brings us to today.

As a result, China now has an enormous middle class and extremely wealthy top tier that gorged on government investments and insatiable demand for growth. And now capitalism’s chickens are coming home to roost, as they do, and investors are beginning to get cold feet. Because that’s what capitalism does. This is their 1980s Reagan moment. Which way will they go? State capitalism or corporate capitalism? Is there really a difference?

So why bring this up? Because it offers interesting insight into the dominance and resilience of the U.S. economy and tells us something about Bidenomics. But it also potentially throws a curveball at the U.S. economy if China can’t regain its footing. All the U.S. stimulus in the world won’t stave off a global recession if China shits the bed.

Bidenomics is essentially Chinanomics. Forget the political or social constructs. From a purely economic perspective, think about what China has done:

- It has offered low cost loans to impoverished nations in return for access to cheap labor and raw materials. (A century ago in the United States we called that “dollar diplomacy.”)

- It printed gobs of money and ran extraordinary deficits to fund domestic infrastructure projects that generated enormous corporate and shareholder wealth. (We did that in the 1940s and ’50s, during Obama’s tenure and now again under Biden.)

- And recently, when the real estate market cratered and caused a banking crisis, it stepped in to shore up the financial sector and offer low cost consolidation loans to real estate investment trusts. (Just like the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations have done in concert with the Federal Reserve.)

Here’s a key difference as well as to how these things are related.

The difference is size and strength. No matter your feelings on American capitalism, the fact remains that U.S. GDP is 5.5 trillion dollars more than China. If that doesn’t seem impressive, consider this. Our population is 330 million. Theirs is 1.4 billion. That means that our GDP per capita is 5.5 times that of China. In short, there’s no fucking comparison, especially if their economy is weakening and even showing signs of decelerating. In 2023, consumer prices in China are going backwards. That’s called deflation, one of the worst things an economy can experience.

Now, here’s why they’re interconnected: The U.S. is China’s biggest customer. They need us. Badly. But China is one of our biggest operating partners in making the shit they need us to buy. If the Chinese people and corporations are holding onto a record amount of cash and prices are falling simultaneously, it means there’s a lot more going on behind the scenes than just fear of a leader and a real estate bubble. There are real cracks in the Chinese economy, and that’s not good for global markets as we look to recalibrate the world’s supply chain.

There’s a very real possibility that the capital flight from Chinese markets will inure to the benefit of U.S. companies and U.S. treasuries. That’s good, right? Good for U.S. companies and wealthy investors. But that’s not exactly middle out and bottom up.

(Wondering when I'm going to talk about Bidenomics?)

Fair enough. Just hold it in the back of your minds that no matter what Biden, the Fed, the major banks or anyone says about recessions, the stock market, GDP or whatever, we’re no longer alone in the world and there are things happening across the globe that will have an impact on the real economy. And that means you and me.

Both the U.S. and China have been pouring ungodly sums of money into the global economy, and this activity has been propping up the global banking sector and domestic real estate markets for quite some time. But China is in a pickle:

- Can’t keep spending money on real estate. (There are already dozens of what they call ghost cities with no one in them.)

- The people are sitting on cash and unwilling to spend it, so direct stimulus won’t invigorate much.

- The United States and Europe have begun to carve new supply chains to the benefit of fresh competitors like India, whose economy happens to be on fire.

- And the U.S. has taken direct aim at two important sectors to the Chinese economy: microchips and renewable energy.

So they have their work cut out for them.

And, unlike China, we are desperately in need of infrastructure investment. For all of Trump’s bluster about infrastructure, it never came to fruition. This is where we pick up on the Bidenomics story. Biden and company are gambling that the investments to be made into the economy through the Inflation Reduction Act will begin hitting the real economy by the time Americans head to the polls. It’s a gamble, but it’s likely the best strategy going forward.

Chapter Two: Behind the Numbers.

Here’s the thing. Biden is a technocrat. Recall that he was in charge of the infrastructure spending under Obama’s 2009 bailout. It was flawless. But guided by Larry Summers’ philosophy of timely, targeted and temporary. Now, for the obvious critique—it took a while to get off the ground and it was a lot of window dressing, though necessary. Roads were paved. The feds backstopped state-run projects. A handful of fixes to federal transportation infrastructure were performed, but nowhere near the overhaul required and what the Inflation Reduction Act tapped into.

And, despite all the hoopla surrounding subsidies to solar manufacturers, that was a drop in the bucket. But it was ultimately successful no matter what the GOP says, which is why you don’t hear them talking about that anymore.

This time around we have a different Biden. He’s not the technocrat in charge, he’s the POTUS. And he’s fucking old! So we have to rely on the capabilities of his underlings to facilitate these projects. For all of my criticisms of Mayor Pete, I have confidence that he will faithfully administer his end of the deal. As for the other agencies, my impression is that there is a high degree of competency, so that shouldn’t be the issue.

The real issue, from an economic perspective, is that we’re missing one of Summers’ “Ts.” These are timely and targeted, lord knows we need these investments, but they’re not temporary. By design, these investments are of a different character. Under Summers, the issue was the amount of money. There wasn’t enough to go around, so that’s why the projects were less substantial. People forget that one-third of Obama’s $800 billion stimulus went directly to the states to fill in budget shortfalls and support Medicaid. Another third went to shoring up unemployment. Leaving the last third for infrastructure.

It’s a drop in the bucket compared to what we’re about to spend over the next nine years.

The administration has dispatched officials to appear on as many programs as possible to tout a few key metrics and tease the fact that we’ve only just begun. So they talk about cooling inflation, historically low unemployment, American manufacturing coming back and achievements like lower prescription drug prices for seniors. You’re hearing these talking points a lot, because they’re true…but also, just about all they have to stand on for reelection.

So, why the low approval ratings? Why the concern? The stress and pressure. Images of tent cities in urban areas. When does the middle out extend to you and me? Are homeless people below the so-called bottom? Destined to be forgotten?

People are right to question Bidenomics. The Democrats are gambling on enough groundbreakings in key states that recovery happens in swing states first and foremost. That’s by design. And if just enough signs go up, shovels go into the ground and contracts start paying out to large companies, maybe, just maybe, Biden will turn 85 in the White House and blow out the candles with his oxygen machine.

Actually, I think that would blow up the Oval Office.

Anyway, that’s essentially a wrap for Bidenomics.

Wait, did I miss something?

No, you didn’t.

A stimulus bill and some drug relief for old people. That’s Bidenomics.

Bidenomics is an over-Keynesian response to the pandemic to make up for lost infrastructure spending since the Reagan administration, and not much more. Monetary policy is being dictated solely by the Fed, which is just beginning to pull back, but there’s more to that story as well. The Fed is also dictating rates in a vacuum and still looking to put people out of jobs in order to curb inflation. And put people out of jobs. (Oh, did I say that already?)

In terms of economic policy, that’s all we’ve got. Spend a shitload of overdue dollars that will pour into the commercial sector to reduce our reliance on foreign partners, shore up an aging physical infrastructure and encourage investments into a renewable future.

Seems like there’s a lot missing.

- A lot. The direct child payment that lifted millions of children out of poverty? Gone.

- Attempts to overhaul the healthcare system and move toward a comprehensive public option? Off the table.

- Student debt relief? Oh well, we gave it a shot.

- Increasing taxes on the wealthy to reduce inequality? That went out the window on the debt ceiling negotiations.

These are the policy measures that actually impact people directly and measurably. There’s no guesswork involved when you have food on the table, a stable job, wages increasing more than the rate of inflation, manageable debt and coverage in the event you fall ill.

What people want is, in reality, so fucking simple that the only American miracle is that we somehow fuck it up.

Instead, our policies are almost exclusively oriented around corporate America. Behind all of the talking points, we’ve got the receipts to demonstrate that Bidenomics is about propping up big business while trying to convince your lying eyes that it’s really all about you.

Middle out, bottom up? Try trickle down, Biden style.

Here’s a high level view of the only figures you really need to know to understand the economy and where we’re headed.

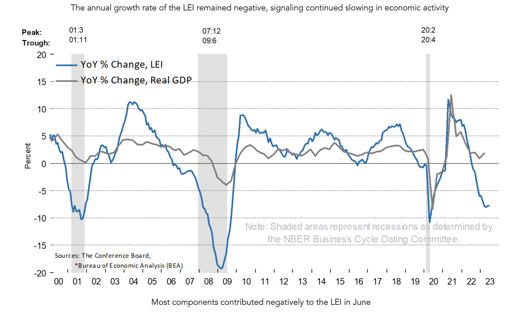

Let’s start off with my favorite. The Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI), for our purposes.

Here’s what the LEI measures:

- Average weekly hours in manufacturing

- Average weekly initial claims for unemployment insurance

- Manufacturers’ new orders for consumer goods and materials

- ISM® Index of New Orders

- Manufacturers’ new orders for nondefense capital goods, excluding aircraft orders

- Building permits for new private housing units

- S&P 500® Index of Stock Prices

- Leading Credit Index™

- Interest rate spread (10-year Treasury bonds less federal funds rate)

- Average consumer expectations for business conditions.

Here’s what the LEI write up said in July, then we’ll talk about why this is so important.

“The US LEI fell for the sixteenth consecutive month in July, signaling the outlook remains highly uncertain. On the other hand, the coincident index (CEI)—which tracks where economic activity stands right now—has continued to grow slowly but inconsistently, with three of the past six months not changing and the rest increasing. As such, the CEI is signaling that we are currently still in a favorable growth environment. However, in July, weak new orders, high interest rates, a dip in consumer perceptions of the outlook for business conditions, and decreasing hours worked in manufacturing fueled the leading indicator’s 0.4 percent decline. The leading index continues to suggest that economic activity is likely to decelerate and descend into mild contraction in the months ahead. The Conference Board now forecasts a short and shallow recession in the Q4 2023 to Q1 2024 timespan.”

Okay, blah-biddy-blah blah, right? Essentially, the LEI is signaling a deceleration at best and a mild recession at worst. What’s useful about this index is that it has been perfect in predicting economic activity over the last half century. One of the reasons it’s such a strong index is because it combines big business items with consumer business confidence, real manufacturing data, unemployment, wages, housing, credit and market predictions where treasuries are concerned. So, when several measures are pulling down, the whole index turns negative and gives us a predictable look forward. So, if the LEI is signaling a recession, even a mild one in an election year, that’s not a great look for Bidenomics.

But team Biden has access to all the same figures we do, right? That’s why the narrative push to convince people that things are perhaps better than they are is so critical, especially in the run up to an election. So that’s the backdrop. Republicans can smell the blood in the water and are rooting for things to worsen, knowing that the next president will inherit the tailwinds that will eventually pick up once infrastructure spending really starts to take hold. Democrats are hoping and praying that deceleration is the worst of it and that the artificial boost resonates in key states ahead of the election.

On the surface, there’s reason for optimism on the Democratic side of things. But it’s also important to dig deep into the numbers. Take Wisconsin, for example; a crucial battleground state that Biden took in 2020 but Trump took in 2016. (Shout out to our Wisco-Badger-F*ckers. All Hail Nettie.) Well, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, Wisconsin has an extremely tight labor market for several reasons, “including an aging workforce and a shortage of young workers interested in jobs in Wisconsin’s manufacturing industry.”

One number, two pictures.

So, Wisco has extremely low unemployment, which the Democrats will see as a good thing as they tout manufacturing expansion in the rust belt. Currently, it boasts a 2.5% unemployment rate, compared to New York’s 4.9% unemployment, as an example. But that’s not the whole picture. In fact, it might work against them. Having a job is great, but having one you like that makes you feel secure is better. If manufacturing is lost on Wisconsin’s youth and the older workforce is aging out, then low unemployment might be a sign of a shifting paradigm in the labor market. Something the figures won’t tell you.

So that’s our backdrop, but now we have to look further into the data to figure out what deceleration or mild recession means for the corporate class versus the working class.

The Corporate Story

Let’s examine a series of charts that together tell an interesting story. We’ll start on the corporate side of the ledger, then move to the consumer. Let’s start with a super macro item that should be of much greater concern to people than it is.

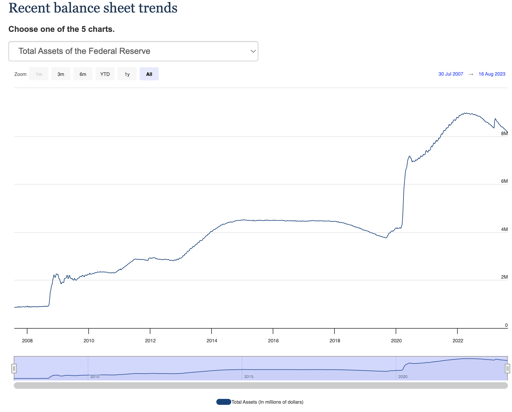

The Federal Reserve Balance Sheet.

If we take a short view on the Fed balance sheet, you can see that it’s beginning to shrink it. What does that mean? Remember, back in 2009 there was a lot of talk about the size of the Fed and how it was buying up treasuries and toxic assets? If you look at it in isolation, it’s a remarkable increase, almost a ninety degree uptick as the Fed stepped in to save the U.S. banking system and essentially prevent the global economy from nose diving into a ’30s-like depression.

At the time, people were outraged. The bank bailouts inspired Occupy Wall Street. Made Bernie Sanders a household name. During the crisis, the Fed balance sheet doubled from $1 trillion to $2 trillion. Staggering. Today, it’s at $8.2 trillion and no one is talking about it. But—and this is a qualified “but”—that figure is down from $8.9 trillion just 18 months ago. So what’s going on here?

Well, essentially, the Fed continued its buying spree to ensure liquidity in the financial markets. At the same time, rates were so low prior to the recent rate hikes that the banks were basically living risk free and participating in legal arbitrage. Free money from the Fed that they could invest back into the market knowing the Fed was backstopping it. It’s the con of a lifetime. So where’d that money go? That leads us to the next chart.

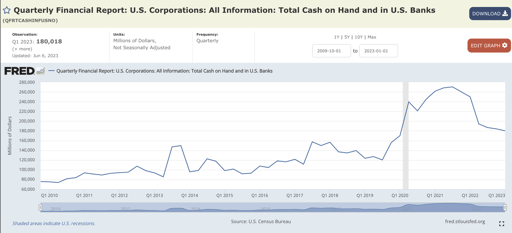

Total Cash on Hand, U.S. Corporations

Non-financial U.S. corporations are holding onto about $1.7 trillion dollars in the bank right now. About twelve tech companies make up almost $1 trillion of that. That’s an impressive number, until you consider that it’s down more than a trillion over the last 18 months, largely because U.S. companies spent their COVID cash on stock buybacks and dividends. And yet, even with such eye-popping sums going into the hands of the wealthiest citizens in the nation, companies are still sitting on ten times the amount of cash they were in 2010 when the Fed was propping up the economy.

It’s important to note that these are non financial institutions, so while there’s a significant element of pandemic money lining their coffers, there’s a bigger reason why companies have accumulated so much fucking cash.

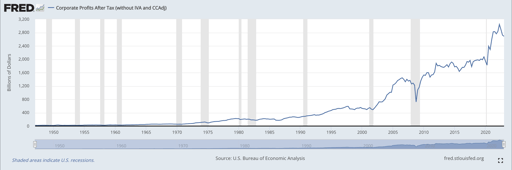

U.S. Corporate Profits

This one rounds out the corporate side of the ledger, and it’s a doozy. Corporate profits, as we speak, for 2023, will be about $2.7 trillion. That’s down from $3 trillion in 2022 at the height of inflation and riding the post-pandemic liquidity phase. The liquidity I’m speaking of, by the way, is among the population. Remember, the real infrastructure stimulus hasn’t hit the economy yet. The biggest payouts were to small and medium sized companies and direct to consumers. So, what did the corporations do across the board? They raised their prices. Or “took price” as we covered in our inflation essays, a reference to the coded language CEOs would use on investor calls, a euphemism for fleecing the public because everyone was flush with cash from the government.

Outside of the inflation elements that were due to the supply chain issues and persistent lockdowns in China, the book is closed as to why inflation was so high in the United States in particular. Our companies simply stole the money out of the pockets of the American people because they could. How do I know this? Because in the year 2000, U.S. corporate profits were at $500 billion. So, over the past two and a half decades, corporate profits have risen 5-fold.

The Consumer Story

The government locked you in and paid you out. Then corporate America hoovered your bank accounts and forced you to dip into credit, all while the Fed punished you by raising interest rates and making car payments, mortgage payments and bank loans more expensive. And we know this for a fact because we can now move to the consumer side of the ledger.

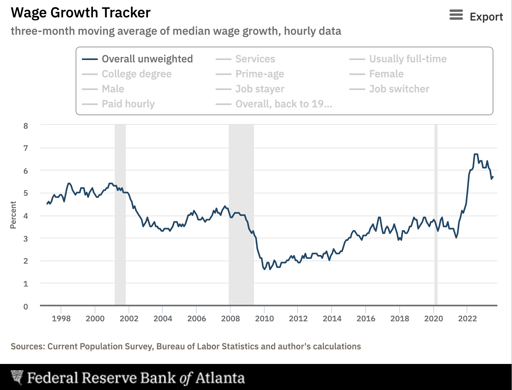

Real Wage Growth

Real wage growth paints an interesting picture. While it looks like growth tracks with recessions and corporate activity, it’s orders of magnitude smaller in terms of rate of change. For example, if you look at average wage growth among employed workers at the turn of the millennium, we see an average growth rate of a little over 5% annually. Throughout the aughts, real wages then went on a steady decline and fell off a cliff during the financial crisis. Wage growth didn’t approach 2000 levels again until 2022, then it took a huge leap forward to the high 6% range, only to find itself retrenching in 2023, where it looks like it will settle in the high 5% range, or slightly above where it was in 2000.

The takeaway here is obvious when you map corporate profits against real wage growth. Despite the brief acceleration in 2022 alone, real wages in this country have stagnated for decades, just barely average more than inflation, which means most people haven’t really gotten ahead, while corporations have been so flush with cash and profits they’ve been pouring into shareholder pockets and creating extreme wealth gaps.

And you can see how corporate America picks our pockets in the next two charts to quickly drive this home.

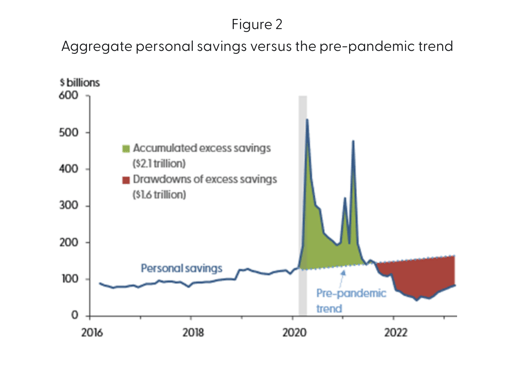

With that, let’s head over to the left coast this time to hang with the San Francisco Fed and check out household savings.

Household Savings

During the pandemic, U.S. households banked a ton of cash from the government. To the tune of $2.1 trillion dollars in accumulated excess savings. Prior to this period, savings had barely budged in recent years. Then, starting midway through 2021 and continuing through today, the same households have been liquidating these savings. The San Fran Fed estimates that $1.6 trillion of the excess savings has already been depleted.

The overlords giveth and taketh away.

The Fed estimates that about $500 billion of excess savings still exists and notes there’s a great deal of uncertainty as to whether this will hold due to an adjustment in the average household savings profile.

In other words, have people depleted enough of their savings that they’re beginning to change their buying habits? Well, this next chart would indicate that this is not happening. But that’s not necessarily a good thing either.

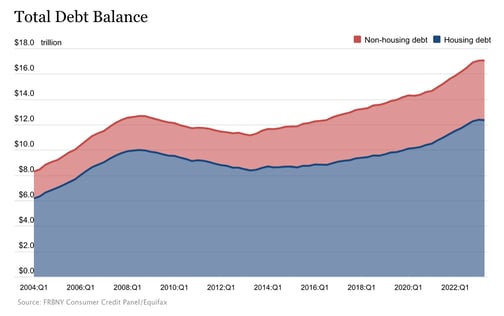

Household Debt

According to the New York Fed, in 2023, U.S. households are carrying $17 trillion in debt. Credit card debt. Mortgages. Student loan. HELOCs. Auto loans. In 2004, that figure was $8 trillion. So, we’ve more than doubled our indebtedness since that time. And back then, rates were low.

So, I guess that answers the U.S. savings question. We might be trying to hold onto our savings by getting 5% in the bank, but we’re paying 24% on our credit cards, 8% on our mortgages and 7.5% on our student loans. No matter how you slice it, they got you.

And that’s the story here, folks. That’s Bidenomics. But also, that’s Bushnomics. Obamanomics. Reaganomics. Call it what you like, the corporate class is winning the race, and the past couple of years, they’ve been winning it going away.

Bring it home, Max.

If Bidenomics was really a good thing, we’d be refinancing student debt and talking about forgiveness.

We’d be talking about reverting to direct child payments to ensure that children don’t fall into poverty.

We’d be investing in a mental health and federal housing emergency infrastructure plan and not just into solar panels and bridges.

Medicare for all would be on the agenda.

So would raising the minimum wage.

I realize these things can’t be done now with a deadlocked and intransigent Congress. That, and election season has officially kicked off, so that’s a wrap. We got what we got from the first two years of the administration and, yes, it was a lot because we were making up for lost time. But to think it’s enough to fill the basic needs of the American people to make them feel secure by the time they pull the lever, I’m not so sure.

For the first time ever, this might be about more than just jobs. It’s a long held notion that sitting presidents, or incumbent parties for that matter, don’t lose elections when unemployment is extremely low like this. But nothing is as it was. Everything is different now.

There’s only one certainty that you can derive from all of these charts. Corporate America has won. It’s over. The neoliberal chapter of the Republic is coming to a close, and we’re entering something new. Wolin’s inverted totalitarianism. Oligarchy. Corporatocracy. Whatever we wind up calling it, know this: until we begin to see our future through the lens of class struggle, we’ll never gather enough political momentum and capital to defeat the corporate class and reverse some of the abuses in power.

Serious question. Why did you spend so much time talking about China up top?

Ah. Fair question. You’ve often heard me throw around the word ‘ethnocentrism’: the tendency to only see ourselves in the world or to see the world around us through an American lens. Well, the way we’re talking about China now worries me. We’re rattling sabres and warning of impending and invisible threats. (Again, read Jeffrey Sachs.) This is all posturing, because we need to feed the war machine.

Who are we as a nation if we’re not fighting an existential foe?

And Posen makes a fair argument that China is increasingly clamping down on corporations and citizens in arbitrary ways. They’re fumbling the ball because they are running up against perfectly normal circumstances that arise when you run a capitalist system. But that’s not why capital is fleeing the country, as I alluded to earlier. So, a couple of things here. First off, we need to back off the rhetoric because another Cold War, or God forbid a hot war, would be catastrophic. It’s stupid. But also, we need to engage with China to align our interests and ensure that they don’t dissolve into a deep recession, because it will drag the rest of the global economy down with it.

So, when we think about Bidenomics, it’s important to pick our heads up and look around.

Europe is struggling right now. India is ascending, but from such a low level baseline, it’s not going to be as important to the global economy as the U.S. and China for the next couple of decades. And, if our policies are so blindly implemented as to impact the rest of the world negatively, we have only ourselves to blame for being so myopic. So, if there is a sudden, but deep and protracted, decline in the Chinese economy, then all the king’s horses and infrastructure bills in the country won’t help American’s feel better at the polls next year.

Are you ready for Trump Part Two, The Prison Administration? President DeSantis? President Ramaswamy?

The reason we’re doing such a deep dive into the history of socialism, anarcho-syndicalism and Marxism is because history can teach us a great deal about the times in which we live. Make no mistake, the paradigm is shifting. The dialectic is resolving in dangerous ways. And, the more we settle for Bidenomics or Trump’s brand of economic pandemonium, the further away we move from shifting the consciousness of the working class in this country. The further we are from recognizing that the enemy isn’t crossing the border, teaching critical race theory or even standing on the debate stage at the Republican primary for that matter. They’re sitting in boardrooms.

Here endeth the lesson.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.