The Controlled Demolition of the U.S. Economy.

Shadow Banks, Dollar Debasement and Basis Trades.

Image Description: The dollar sign exploding and expelling little pieces.

Image Description: The dollar sign exploding and expelling little pieces.

The U.S. economy is headed for financial collapse. Repo market stress. Private credit market liquidity crunch. Subprime lending crisis. Spiraling deficits. Basis trade exposure. Dollar debasement. U.S. states in recession. Oil market contango. Tariff and trade wars. Each of these are like explosive devices hiding in the corners of the economic edifice that is the U.S. economy. And the Federal Reserve just released a shocking paper that exposes the biggest potential threat of all. Explosive devices have been set all around the economy and a new bomb was just uncovered in the most unlikely of places.

We are headed for an economic collapse that will rival the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Our response to it will determine whether it’s even worse than that. The housing market was a single ticking time bomb with an enormous blast radius that few understood. It’s difficult to imagine what it would be like if there were more of them.

Repo market stress. Private credit market liquidity crunch. Subprime lending crisis. Spiraling deficits. Basis trade exposure. Dollar debasement. U.S. states in recession. Oil market contango. Tariff and trade war.

Explosive devices have been set all around the economy and a new bomb was just uncovered in the most unlikely of places.

Much of this story isn’t the Trump administration’s fault. Yet some of it is exclusively their fault.

All of it is now their problem.

The Road to Economic Hegemony

Over the past couple of years we’ve concentrated on three pivotal moments in the development of the U.S. economy. Bretton Woods, the end of it, and the Global Financial Crisis. There are crucial moments in between but together these three events explain U.S. economic hegemony.

The Bretton Woods system made the U.S. Dollar the centerpiece of global trade. As the world’s reserve currency, it meant that trades that didn’t even involve us would be settled in dollars. As such, nations and multinational corporations needed to get their hands on dollars in order to transact with one another. The proliferation of dollars allowed us to scale our industrial sector, which was already primed coming out of World War Two, but it was also inflationary as the value of the dollars was still pegged to a physical store of gold.

While reserve currency status meant that there would theoretically be unlimited demand for dollars, if the bulk of these dollars were put to work in the U.S. economy then inflation would be a feature. To remove dollars from the system, the United States maintained extremely high levels of taxation. But even still, inflation risks remained.

Because the U.S. post-war economy was able to absorb an increase in monetary activity through investments into manufacturing and services, inflation and wages rose in parallel throughout the 1950s and ‘60s. But as taxation levels steadily decreased over time and more money was left circulating through an ever maturing economy, inflationary pressures began to creep into the economy again as we came into the 1970s. The Nixon administration made a somewhat spurious economic claim that the gold standard left us vulnerable to runs on the dollar and made the surprising and unilateral decision to remove the gold peg to the dollar, thus ending the Bretton Woods era to a large degree.

What happened in the decades since was utterly transformational. It was as though U.S. leaders didn’t fully recognize the magnitude of this decision in fiscal policy terms. The Carter administration, for example, continued to operate under the strict notion of balanced budgets. It operated on fiscal austerity at a time of global economic weakness, despite the newfound power of floating fiat reserve currency at its disposal. The combination of a rapidly expanding money supply, a devalued dollar relative to foreign currencies and shocks to high input cost commodities (such as oil), rocked the U.S. economy and sent inflation spiraling. All the while, the Carter administration tightened its belt on fiscal spending measures while the Federal Reserve tried choking investments with insanely high borrowing rates.

Beginning with the Reagan administration, policymakers in D.C. began experimenting with monetary and fiscal policy to encourage rapid expansion of both the money supply and investments. Industries were rapidly deregulated. Money circulated more freely. Taxation levels fell dramatically. European and Asian markets began to mature while new Eastern European markets came online after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The U.S. dollar was once again in high demand, and U.S. financial institutions were all too willing to find places to invest them. Chief among them was the U.S. equities market.

Though some fiscal policy features changed over the course of several administrations, the financial markets operated independently. Money was abundant. Rates were manageable. Regulations were loose. There were normal boom and bust periods, features of a capitalist system, but by and large the money just kept flowing. So much so, in fact, that Wall Street struggled to find places to invest it all. Demand for investment return drove Wall Street to develop more sophisticated products and packages like swaps and derivatives. Essentially bundles of bets on bets with hedges to the upside and the downside. For every stock, bond or financial instruments, there were hundreds and thousands more betting on the performance of those instruments. And for every dollar bet placed on the roulette wheel, there was a bank willing to give the gambler five, ten, a hundred times more in leverage against it.

It all came to a head in 2008, and it all came apart in 2009. The cheap and easy money. The wild gambles and Rube Goldberg leveraged financial packages came together like a ticking time bomb. And when the bomb went off, the collateral damage spread like wildfire through the country and then the rest of the world.

Our problems today rest in the responses of yesterday; each decision, just another jenga piece taken from the foundation and laid on top of it.

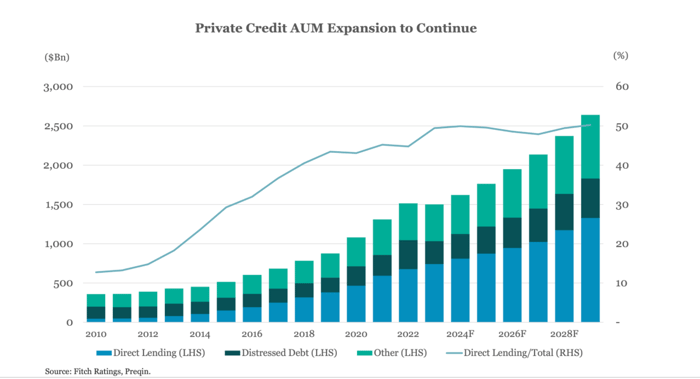

Today we have two financial systems. The one that was stitched back together in the wake of the ‘08/‘09 crisis, and the one that developed adjacent to it. This secondary market is now as big as the primary banking system. The technical name for it is Nonbank Financial Intermediation (NBFI) market. But most in the industry just call it the shadow banking system.

It sounds conspiratorial, but it’s real. For our purposes, we’ll call it the shadow banking system. It includes money markets, hedge funds, venture capital firms and sovereign wealth funds. A significant element of the shadow banking system is lending, or private credit lending. This part of the shadow system has grown dramatically in the wake of the financial crisis for two reasons. The first, regulations. The second is capital requirements.

In its first term, the Obama administration and Congress moved quickly to shore up the financial system by coordinating Federal Reserve and Treasury activities to flood the banking sector with liquidity and provide incredibly low cost capital. The Federal Reserve purchased toxic investments from bank balance sheets. The government acquired shares of corporations so they had the cash to work through their own toxic debt. And it developed a system of reporting requirements for banks of all sizes and increased the amount of money banks were required to keep in reserve balances.

And then, it stopped there.

What didn’t stop was the flow of capital to the banking sector and near-zero interest rate policy. These factors continued long after the large investment and commercial depository banks had worked through their toxic debt issues. Money became both cheap and available. It was like leaving a toddler in a candy store and saying, “I’ll be back in a couple of years, keep an eye on things.”

Because the regulations and capital requirements remained in force, the banks technically couldn’t invest in risky activities and lending. So they found others that could.

Source: The Lead Left

The simplest way to explain the build up in tension outside of the banking system is to keep in mind the concept of cheap and easy money. As long as financial institutions have abundant access to cheap money they’re going to find a way to deploy it. That’s exactly what they did.

Parking money in the shadow banking sector is the easy thing to track. All we need to do is look at the growth of investment firms like BlackRock and Apollo to know where the money is flowing. Because these firms aren’t held to the same regulatory standards as banks, they need only to maintain solid payment records on the money they receive from the banking sector so everyone gets high marks from the credit rating agencies. But this is only one part of the story. It turns out that these shadow institutions had another source of investment capital all along: The U.S. Treasury.

This is where our story really begins.

Controlled Demolition

Think of the U.S. economy as a building. At the foundation you have the banking system. This is the substructure that controls the operations. The elevator room. Heating and cooling. Power and electricity. Plumbing. Above ground you have the real economy on the first several floors. All of the manufacturing, agriculture and services industries ingesting the air flow, power and water from the banking system below to make their operations hum. On the top floors you have the government entities that watch over them, provide guidance and defense. The employees of all of these places are in their offices and cubicles. You, me, bankers, welders, doctors.

If one of the floors suddenly fails—maybe the air conditioning stops, all the employees quit, the plumbing stops working, whatever—the rest of the building has the capacity to absorb the shock and then the powers that be from top floors come in to assess the damage and hopefully fix it. It’s a sophisticated system, almost living and breathing.

If you want to take down a building of this magnitude you would do more than plant a bomb on one of the floors. This might do some temporary damage and hurt a lot of people, but it’s unlikely to take the whole thing down. To take down a building of this size you would have to do a controlled demolition and attack it from all angles, both inside and out. So let’s talk about explosives.

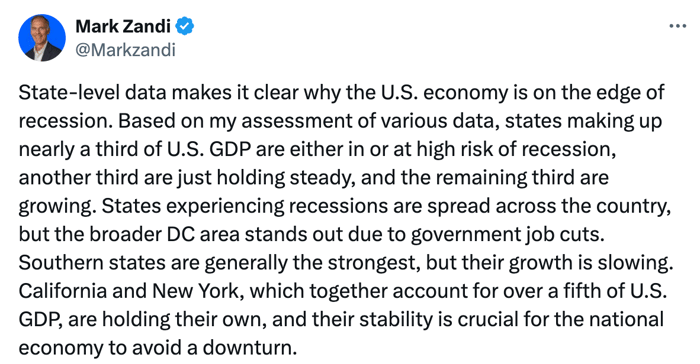

Moody’s Gets Moody

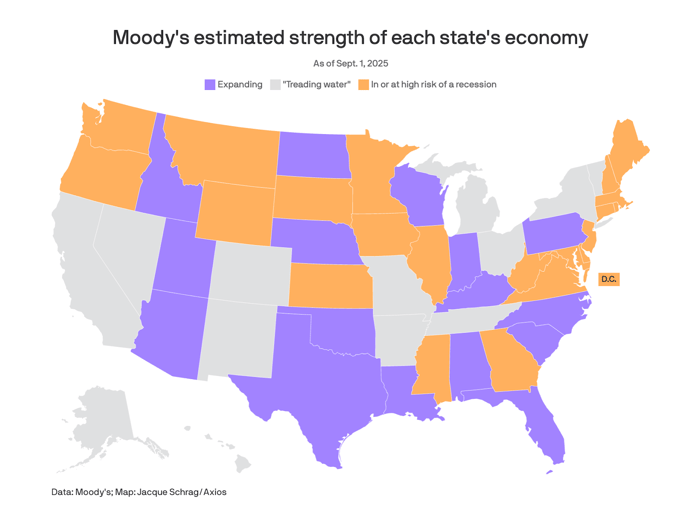

Mark Zandi from Moody’s Analytics set off a brief firestorm when he released indicators showing that 22 U.S. states—plus Washington D.C.—are either already in recession or teetering on the brink. That’s nearly half of American states in economic decline right now, while the White House keeps telling us everything is tremendous.

Zandi’s state-level recession index isn’t just looking at employment numbers. It’s drawing on jobs data, personal income, modeled industrial production, housing starts, credit performance, and migration patterns. And what it reveals is a patchwork economy with startling differences from state to state.

The recession-impacted states are geographically scattered but concentrated in the Midwest, the Plains, and the Northeast. What do they have in common? Federal job cuts, especially around Washington D.C. Slowing immigration that had been filling crucial labor gaps. Rising tariffs that are hammering trade-exposed regions. And declining manufacturing sectors facing weaker demand for goods as global trade contracts. That part doesn’t get enough attention. We’re six months into the heart of Trump’s tariff regime and manufacturing isn’t gaining or stabilizing, it’s losing ground.

Source: Axios

So these aren’t random economic hiccups. These are the direct consequences of policy choices—tariff wars that make American manufacturing less competitive, immigration restrictions that leave farms and factories short-handed, and federal workforce reductions that ripple through entire regional economies.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. While 22 states are sliding backward, another third are just “treading water”—barely keeping their heads above the surface. But there’s this group of Southern states—South Carolina, Florida, Texas, North Carolina—that are still in expansion mode. Why?

Strong population inflows, for one. Census data shows the South has seen massive in-migration since 2020, driven by affordable housing, lower taxes, and more business-friendly environments. These states experienced a boom in real estate and construction as a result of post-COVID migration. More people means expansion in services as well—professional services, healthcare, financial activities, leisure and hospitality—so this inflow has provided some insulation. Defense and aerospace investments have also benefited southern economies as one of the few areas of the government where spending has increased.

States like South Carolina are leading the nation in personal income increases and job gains, outpacing national averages. On paper, they look great. But look deeper and a grainier picture emerges—and this is where the Trump administration’s policies become a ticking time bomb even for states that are currently thriving.

The government shutdown over federal Medicaid support is vital to understanding what’s at stake for the economy. Many of the not-yet-in-recession states are the ones with the highest reliance on Medicaid support from the federal government.

Mississippi gets 81–82% of its Medicaid costs covered by Washington—the highest in the nation—and Medicaid represents about 25% of Mississippi’s entire state budget. Kentucky is at 81% federal support with Medicaid making up 33% of their budget. New Mexico is at 80% federal funding, covering 34% of their total budget.

West Virginia, Arizona, Arkansas, Alabama, South Carolina, Oklahoma—all receiving 70–80% federal support for Medicaid, with the program representing anywhere from 22–34% of their state budgets.

So what happens when you slash funding to a program that represents a third of a state’s budget? It’s a nightmare in the making. And it should be noted, by the way, these are all red states. It’s just unbelievable that you have Democrats standing up to red state Republicans. These cuts will force states into impossible choices—either raise taxes dramatically during an economic slowdown, or gut healthcare, education, and other services. Either option kills jobs.

Bomb No. 1 is state budgets and the prospect of mass layoffs and surging demand for social insurance programs the Trump administration is trying to gut.

Contango

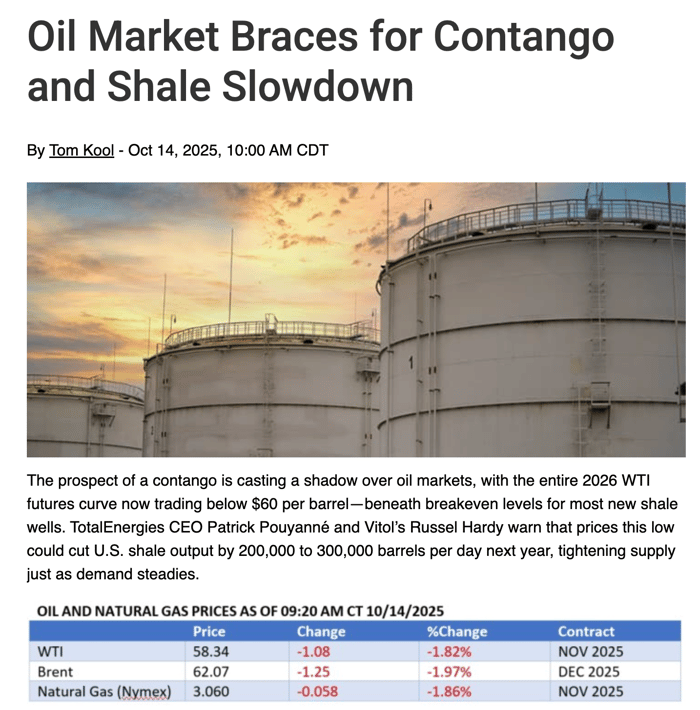

Right now crude oil is trading below $60, which means most U.S. oil and gas companies are losing money on drilling. Contango in the crude oil market means that oil traders expect prices to be higher in the future than they are today.

Source: OilPrice.com

That might sound like a good sign for the oil traders but this specific scenario is actually a negative sign. The projected growth in oil prices is related to slumping global demand and projected cost to store excess capacity. The cost of storage—renting tankers, maintaining facilities, insurance—pushes up the price of future contracts. So you get this inversion where oil is cheaper today than it will be six months or a year from now.

Contango is a giant red flag that demand for oil is weak, which points to broader economic problems—slowdowns in global manufacturing, reduced shipping activity, less air travel. When businesses and consumers are using less oil, it tells us that economic activity has slowed down significantly. Maybe because of reduced consumer spending. Maybe softening industrial output. Maybe financial stress spreading across countries.

Persistent contango, especially when accompanied by rising oil inventories, is often a warning sign that the world economy is experiencing a slump or that a recovery has stalled completely.

And here’s the direct connection: Trump’s tariff war has artificially slowed down global trade projections. Remember all those companies that front-ran tariff deadlines by rushing to import goods before the new taxes hit? That artificially propped up the global freight market for months. But now? Orders are slowing. Hiring forecasts for the holiday season are dismal. Layoff announcements are accelerating.

Why is global economic activity slowing? Because we’re still the largest consumer market in the world, and our erratic trade policies have thrown sand in the gears of global commerce. When the United States suddenly becomes an unreliable trading partner, when tariffs can be imposed or removed on a whim via presidential missive, global businesses pull back. They delay investments. They reduce orders. They wait to see what fresh chaos tomorrow brings.

The contango in oil markets is directly reflecting Trump’s policy chaos. It’s the physical manifestation of global economic uncertainty caused by one man’s inability to understand how trade actually works.

Softening demand means fewer imports as well. And because the Trump administration’s entire revenue plan is built around tariffs, then fewer imports means less tariff revenue. Every economist on the planet predicted this inevitable feedback loop of negativity but this administration pressed on with this agenda. So here we are at the self-fulfilling conclusion of it all.

So bomb No. 2 isn’t just about contango; it’s what it portends for the U.S. budget deficits. If the single biggest new revenue plan suddenly seizes up, then deficit spending will accelerate beyond the already outrageous projections. This will force the U.S. Treasury to raise more debt through treasury auctions that the market is increasingly rejecting.

Debasement

This brings us to debasement—specifically dollar debasement. This refers to the sharp and highly publicized decline in the value of the U.S. dollar throughout 2025. And we’re not talking about a minor adjustment here. The U.S. dollar index fell by nearly 8–11% in the first half of 2025, marking the most significant depreciation since the early 1970s. Think about that. The worst dollar decline in over 50 years.

Investors have responded by shifting assets away from the dollar and toward inflation hedges—especially scarce assets such as gold, which is up over 50% in 2025, silver and even bitcoin. This movement has a name: the “debasement trade,” where investors seek scarce assets as protection against a declining dollar.

So what’s driving this? Ballooning U.S. budget deficits for starters. There are also building expectations of easier monetary policy—meaning investors know the Fed is going to have to engage in some form of quantitative easing again. Then there’s persistent inflation despite interest rate increases to hold it in check. Global de-dollarization, with central banks around the world actively diversifying away from the dollar. And political uncertainty about U.S. fiscal sustainability.

The weakening dollar raises import costs for American consumers, which could reignite inflationary pressures. So we can’t even take advantage of those cheap oil prices. It erodes the real value of dollar-denominated savings and bonds. Sure, a cheaper dollar provides some support to U.S. exports but, again, manufacturing is only 10% of U.S. GDP and, as we said before, it’s shrinking despite what Trump tells you.

People like Scott Bessent will tell you that U.S. Treasury auctions are still finding buyers. And that’s fair. But what we don’t know is who is doing the buying because the buyers have changed dramatically in recent months. We’re seeing a shift from institutional investors—the stable, long-term holders like foreign central banks and pension funds—to private buyers. That’s not a sign of strength. That’s a sign that the traditional pillars of dollar demand are backing away.

The world is losing faith in the major economies to manage budgets responsibly and institute stable trade agreements to get the global economy back on track. Everything is reorienting as a result of Trump’s chaotic behavior and policies. The dollar’s role as the global reserve currency, which has been America’s superpower since World War Two, is being actively undermined by the very people claiming to make America great again.

Another bomb set in the corner of the substructure of the building. That’s three major areas of impact to this controlled demolition of the economy. All made possible by reckless deregulation, profligate money printing, a refusal to pursue any rational tax policy, irresponsible trade wars and every employee at the circus replaced by a clown. And that’s not all. There’s another hidden charge in the substructure that was only just uncovered, and it might be the one with the fuse.

Cockroaches

There were two high profile bankruptcies in early October—Tricolor and First Brands Group—that raised eyebrows at first on Wall Street, followed by alarm bells when two regional banks disclosed trouble on their balance sheets. These events prompted JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon to remark on an investor call:

“And I probably shouldn’t say this, but when you see one cockroach, there are probably more…Everyone should be forewarned on this.”

The stock market reacted negatively at first then quickly reversed to continue its remarkable bull run. When the dust settled from the announcements, some came to believe that these were indeed isolated events related to fraud. In the First Brands Group filing it was disclosed that as much as $1.9 billion from its lending arm had simply disappeared. A clear case of fraudulent reporting between counterparties. Zions Bank and Western Alliance, the two regional banks that reported potential loan losses, were both purportedly related to the same borrower, California-based Cantor Group.

Wall Street’s sigh of relief that the troubles of Zions Bank, Western Alliance and First Brands Group are likely related to fraud and poor underwriting has obscured the first domino in the October uneasiness: Tricolor.

Tricolor is a subprime mortgage crisis throwback but in the auto loan sector. Most of its borrowers didn’t even have a credit score and more than half didn’t even have driver’s licenses. And yet, the loan volume was so robust (of course it was) that it counted Fifth Third Bancorp, Barclays and JPMorgan Chase among its capital suppliers. This is how the subprime shell game continued after the global financial crisis. Highly regulated banks are still engaging in risky lending practices, but they’re maintaining an arms-length distance.

A staggering amount of commercial and residential loans, business, student and auto loans, and risky revolving lines of credit are issued through these NBFI institutions but the capital originates from the commercial banking sector.

Since the Dodd-Frank regulations implemented after the financial crisis, banks have increased the supply of capital to private corporations like hedge funds, venture capital firms, investment banks and private credit lending firms. This is where the term “off balance sheet” comes in. These are massive lines of credit or facilities and so long as they are receiving regular interest payments, there is an assumption of general health. The only problem is that we can’t see the individual loans and portfolios on the private side of the ledger. All we can see is whether they are customers of the more transparent banks.

For example, Wells Fargo might show a healthy lending relationship with high profile firms like Blackstone or Apollo. These firms are so well capitalized companies that if a small percentage of their lending portfolios was under duress, we wouldn’t know.

But there are mid-market and subprime market lenders that are themselves enormous and have staked out risky positions in commercial lending. These lenders might have secured facilities at 200 to 300 basis points above the Fed Funds Rate. In turn, they lend money into the secured and unsecured marketplace at 9% to 15% (sometimes higher.)

If a handful of these loans run into trouble, lenders might repackage them at lower rates to maintain a healthy balance sheet. Some firms are engaging in what’s called payment in kind (PIK), loans where they take equity in their borrowers in lieu of interest and principal for a period of time. So long as these troubled loans don’t fail en masse, the surface of the banking sector and the private credit market looks to be stable. But if all of a sudden, as happened from 2007 to 2008, a wide range of loans go south, these cracks turn to chasms. In other words, we might have more than a family of cockroaches living behind the cabinets. We might be facing a whole house infestation.

Collision Course

The money in the banking system comes from the Federal Reserve. That’s how the world works. The Fed loans money to banks at favorable rates to capitalize them. In turn, the banks lend this money out to the world and earn the difference. In our scenarios, the Fed loans money to the banks who loan money to customers and other lenders who also loan money to the public. There are a lot of hands on this cash.

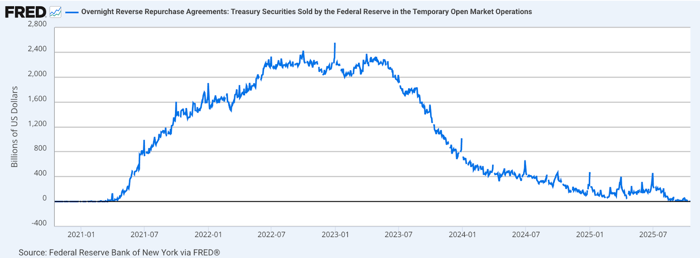

Importantly, banks and corporations will also use this money to purchase treasuries from the government at set interest rates so they always have a nice buffer. Every so often, however, the broader market becomes illiquid. Meaning, there’s more money in loans that have to be settled out than the banks have in cash on hand and so things get a little tight. In these instances, the Federal Reserve will supply additional money by either printing additional bank notes and buying securities from the banks (replacing assets with cash) or by releasing money from a rainy day fund called the standing repo facility.

Here’s just one problem at the moment:

The standing repo facility (rainy day fund) at the Fed is empty. That money has been depleted because the Fed has had to purchase treasuries to fill the U.S. Treasury’s bank account. Why? Because we have to fund the government and the deficits are growing wider and wider because we refuse to tax wealthy people and corporations. Now for the scary part.

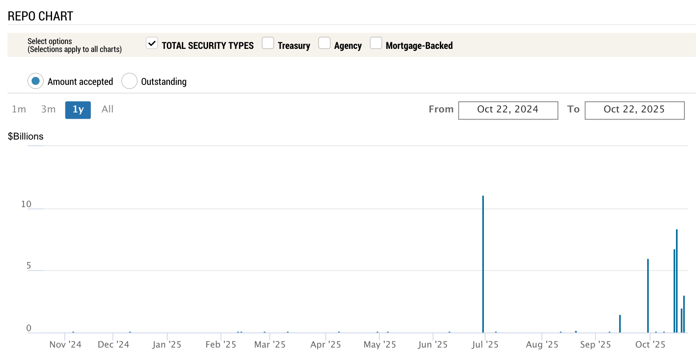

At the end of each fiscal quarter, U.S. corporations move a lot of money around to try and clean up their books for quarterly reporting. And twice a year they sell a bunch of securities to pay corporate taxes. During these (very predictable) times, the Fed will pump up liquidity to make sure everyone can buy and sell whatever they need to. But on several occasions this year (prior to October) it hasn’t been enough, and so they’ve had to step in to inject even more money into the system (as seen by the chart below from the New York Fed.)

The liquidity injection points prior to October fall on quarter-end days and tax deadlines. Again, not unusual but also not a great sign.

And then, something broke in October.

Throughout October, firms have repeatedly dipped into the Fed Repo operations to secure enough liquidity for market settlements. While the total daily volume is in the billions of dollars and therefore entirely manageable, the point is that it shouldn’t be happening at all, let alone repeatedly. In short, this is unprecedented.

The only times this has happened in recent memory is COVID. We can’t even look to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) for guidance because many of these backstops were created in the wake of and because of it. So this is new. And it’s unsettling because it means that the private credit market might be running out of money.

When things like this happen it sends a signal to the managers of the U.S. economy, not simply the Federal Reserve. These are the moments when the heads of the U.S. Treasury, the Federal Reserve, Senate Banking Committee, the White House and the nation’s largest banks—who are also members of the Fed—assemble to address broader issues in the market. Only government oversight can compel these companies to open their books so we can stress test this important shadow banking sector. Otherwise, we’re in the dark.

And right now, the Fed Chair is under fire from the White House. The head of the Treasury is actively running the effort to replace him. The president is completely out of touch and the government is shut down. And the big banks? These are the same people who destroyed the financial system 15 years ago.

This is just one sliver of the entire system. And let me reiterate that if these markets explode, the banking sector will be fine. It’s not like last time. Banks are still sitting on just under $3 trillion in cash and marketable securities that the Fed will happily backstop by converting mortgage packages and treasuries to cash. But the private credit market exposes something more raw and fundamental about the economy.

So we have internal signs from Moody’s that half of the states in the country are in recession. We have external signals from the contango oil market that the global economy is in distress. Regional banks face concentration risk in commercial real estate and private credit suppliers might be pushing leverage limits. And signals all around that the official investor class is hedging against the U.S. economy by moving away from the dollar.

It’s in this last arena that the biggest hidden explosive might be hiding.

The Hidden Bomb in the Building

This is brand new information and I don’t think the world or the markets have wrapped their minds around it just yet. And I’m going to do my best to make this accessible.

In July of 2025, the Financial Stability Board, an international body that monitors the global financial system, issued a report titled “Leverage in Nonbank Financial Intermediation.” The paper takes aim at the lack of oversight into the NBFI market and the amount of off-balance sheet leverage in the system. Essentially, banks are allowing these shadow banking firms to gamble on loans and securities with extreme leverage, sometimes upwards of 100 times. According to the paper, “if not properly managed, the build-up of leverage creates a vulnerability that, when subject to a shock, can propagate strains through the financial system, amplify stress, and lead to systemic disruption through two main channels.”

The first channel is the originating position that is forced to unwind certain assets. This leads to “unexpected liquidity demands.” This can, “depress asset prices further, causing a feedback loop of additional liquidity demands and risk reduction that impacts other market participants exposed to the same asset class.” In this case, think of the effect on home prices as an asset class when the mortgage-backed securities trades started to unwind in 2008.

The second channel involves counterparties, the firms that stand on the other side of the trade. This could range from commercial banks and shadow banks that help syndicate the products to the U.S. Treasury. An unwinding or liquidation of distressed entities could “impose direct losses on their counterparties, leading to a cascade of financial stress resulting in forced liquidations.” Once again, this is what happened in the housing crisis. Banks, brokers, NBFI lenders, insurance companies and traders were all caught in the cascading crisis. At the center of it, of course, was the consumer.

It’s important to note that the FSB is an international organization so it’s warning of systemic global risk, not just here in the United States. But our increasingly globalized world has made all of these markets interconnected and interdependent. A collapse of one or a few markets in the United States would have a ripple effect throughout the global economy once again.

That’s the backdrop to explain the most bizarre revelation in recent days.

Then there’s this statement:

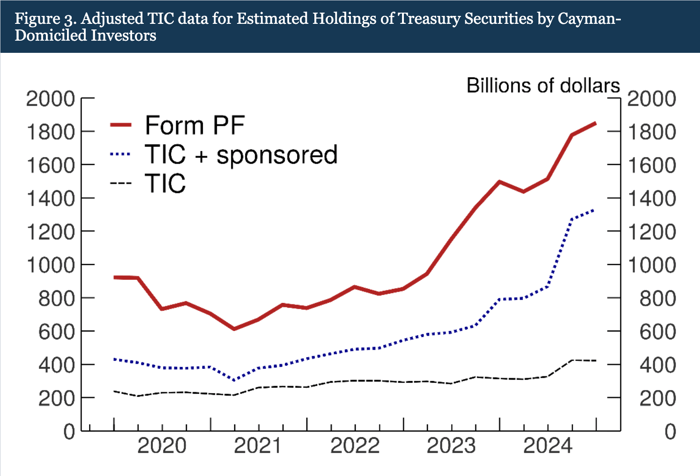

“The puzzling disconnect between the TIC and Form PF data on Cayman Islands’ holdings of U.S. Treasuries is under active investigation.”

I’ll explain more about this statement, but let’s provide a little context first.

Because the U.S. is running such extravagant deficits, it has had to issue more and more debt through treasury auctions. The “sell America” narrative began to take hold in April of this year when Trump announced the “Liberation Day” tariffs. Recall that the administration almost instantly backed off the most extreme rhetoric because of the extremely negative response in the bond markets. (Thus earning Trump the nickname TACO—Trump Always Chickens Out.)

When the bond market collapses suddenly it presents enormous risk to the global markets, once again because of the amount of leverage in the system. As insane as it sounds, the treasury market is also an enormous gambling sector with trillions of dollars flowing through it. Something called a “basis trade.” This is a very common trade in the commodities market because it allows participants to hedge against price fluctuations in the future. Turns out there is a staggering amount of basis trading in the treasury market.

Basically, every bond has a futures contract associated with it. So you have the present day bond and what it might be priced at in the near future. In a basis trade, an investor will purchase whichever one is cheaper, sell the more expensive one and hope that the values converge over time. When you close out these positions, there is a small amount of profit. And I mean tiny.

Because the treasury markets are so stable and short-term notes aren’t typically all that volatile, these trades are as close to a “lock” as the market offers. The problem is there isn’t a whole lot of money to be made. That’s where leverage comes in.

NBFIs, most notably hedge funds, are very active in this market. In order to make these trades worthwhile, they will borrow excessive amounts from investment banks to leverage these trades. So if they have $100 on one position, they might borrow 100 times that amount to make the investment worthwhile. This means that most of the money in the market is borrowed.

So what happens when this sure thing becomes less sure? Here’s where our storyline converges.

Because the margins on basis trades are so slim, even small market disruptions can trigger rapid losses, forced selling or systemic stress. This dynamic is what regulators, including the Federal Reserve and the Financial Stability Board, have recently highlighted as a potential financial stability risk, especially as many of these leveraged funds operate through offshore entities in the Cayman Islands to take advantage of lighter regulation.

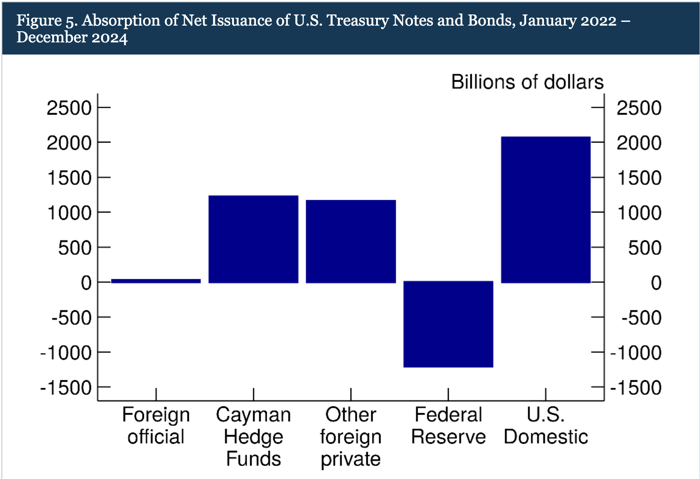

It was understood for quite some time that hedge funds have significant exposure to U.S. treasuries. For several years foreign central banks have been moving away from purchasing U.S. Treasuries. But this trend accelerated when Trump was re-elected and went on the warpath against trading allies and foes alike. The combination of America-first policies that gutted foreign aid and an all out tariff war with the world, forced foreign central banks (referred to as “official sources”) to reduce their holdings of U.S. treasury securities in favor of other currencies and physical commodities such as gold and silver.

Despite this trend, U.S. treasury auctions to fund our ever-increasing deficits continued with relative ease. “Private sources” simply moved in to take up these positions. This gave the Trump administration the ability to calm the bond markets and claim that the “sell America” narrative was false and overhyped.

And then, on Oct. 15, the Federal Reserve released what can only be considered a bombshell announcement.

Until this paper was released, it was believed that hedge funds held around $400 billion in short-term treasuries. These purchases weren’t acts of patriotism, they were making money on basis trades as described above. This amount came from what’s known as Treasury International Capital (TIC) data from the U.S. Treasury. But the Federal Reserve dug into Form PF filings (hedge fund trading disclosures to the SEC) and uncovered something very, very different.

The form PF filings show that hedge funds registered to the Cayman Islands are holding onto more than $1.8 trillion in U.S. treasury securities.

It’s hard to know where to begin with this information.

The fact that the two primary economic agencies in the country, which are themselves the biggest in the world, have a $1.4 trillion reconciliation problem is alarming. Even more troubling is, once again, these hedge funds aren’t purchasing treasuries to perform their patriotic duty or simply earn the stable returns these notes offer. They’re leveraging them to the hilt to profit from the basis trade.

That means that any marginal disruptions or changes in value to the upside or downside—essentially any variation beyond the expected maturity—means that these hedge funds have massive exposure.

It also means that our debt is held in what can only be considered a ponzi scheme.

In the same Fed report, they extrapolate treasury purchases to re-order them from 2022 to 2024. It shows that almost all of the net new purchases of our debt comes from domestic sources (U.S. banks and corporations), foreign private entities (non-central banks) and hedge funds in the Cayman Islands.

Again, on the surface it doesn’t matter who holds the debt so long as the returns are stable and there’s a market for new auctions. The problem is the amount of untold leverage in the system from private sources with opaque balance sheets.

The Upshot

This is the definition of a gathering storm. Our deficits are increasing daily as is the cost to finance them. Repo market stress reveals liquidity strains in the capital markets. The implosion of subprime lending markets from student debt to auto loans signifies a hollowing out of the lower end of the economy. Extreme leverage in the private credit markets is bleeding out with signs of defaults and fraudulent activity. And the disconnect between the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve couldn’t be more extreme at the precise moment when close coordination is required.

I’ll add one last layer to the equation. The 2020 pandemic masked what was shaping up to be a business cycle recession. Several key indicators (outside of the stock market) demonstrate in hindsight that we were likely heading into a shallow recession at a minimum. Perhaps something bigger. This would have made a great deal of sense considering we were due for a late cycle downturn. Instead, we injected $4 trillion dollars into the economy over an 18 month period.

A flood of deficit liquidity combined with a forced shutdown of the global economy and reordering of the supply chain caused all the economic indicators we normally rely on to predict market activity to go haywire. Therefore, visibility is already reduced. These explosives hiding in the corner of the economic edifice would have been hard to spot but not impossible.

Had we stayed the course with a highly technocratic Democratic regime we might have the ability to present a united front and coordinated response to a forestalled downturn. (Think Obama and the GFC recovery.) It would have been insufficient and slow and the consumer would have paid the price to bail out the bankers again, but it would have been familiar. Painful, but familiar.

Instead, we elected a person who decided to plant his own explosives around the building to help with the controlled demolition of the economy. Slashing taxes to further deplete the treasury coffers. Imposing the highest tariffs in history on all of our trading partners. Reducing regulations and oversight on the financial markets. And just to add more gas to the fire, he’s pitting the only two agencies that can save us against one another.

- Repo market stress.

- Private credit market liquidity crunch.

- Subprime lending crisis.

- Spiraling deficits.

- Basis trade exposure.

- Dollar debasement.

- 22 U.S. states in recession.

- Oil market contango.

- Tariff and trade war.

These are the explosive devices planted in every corner of the economy. And this doesn’t even touch on hard economic data like unemployment, inflation, housing and consumer debt. If ever there was a time for steady hands, brilliant minds and a plan to completely reorient the economy away from the top 1% and to the 99%, it’s now. Instead, we elected a human molotov cocktail dead set on setting the whole thing ablaze.

But at least we’ll have a new ballroom to show for it all.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.