Strike!

Reality checking the labor movement.

Image Description: A crowd of WGA and SAG AFTRA Strikers gathered in summer of 2023.

Image Description: A crowd of WGA and SAG AFTRA Strikers gathered in summer of 2023.

This is a critique, not a criticism. (A difference without a distinction?) Perhaps. But I think it’s an important conversation that we need to have.

Let’s talk about the good, the bad and the reality of union actions in the United States. Here’s my thesis statement: While there are multiple high profile labor actions happening across the United States at this moment, there is no such thing as a labor movement.

Aaand…cue the hate mail.

Here’s the thing. What Shawn Fain—head of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union—is doing right now is a masterclass in disruption. I’m a fan. The UAW revealed a hardcore strategy to send workers to the picket lines at all three of the major Detroit-based automakers. About 13,000 workers in all. Nothing I’m about to say should take away from this show of strength and solidarity.

But?

But, if we add these 13,000 to the most recent figures as of August, this brings the national total to somewhere around 325,000 workers who are out on strike.

That’s no good?

Depends how you define “good.” The auto workers join the striking members of both the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) who have been out since the middle of the summer. WGA and SAG members represent 170,000 of the 325,000, or a little more than half. These are hard and fast numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

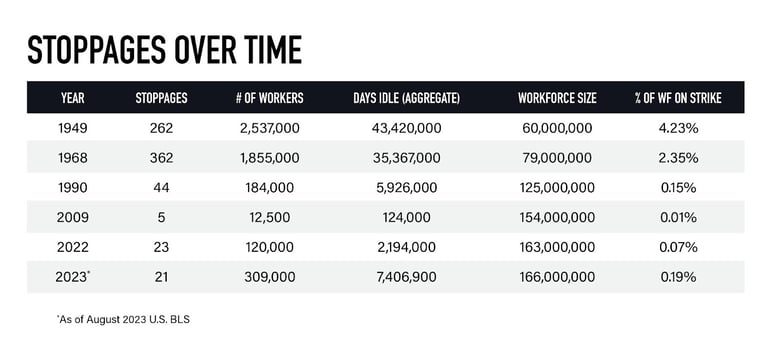

To put this in historical context, I built a simple chart (below) that looks back over several important years in the United States. 1949, ‘68, ‘90, ‘09, 2022 and so far this year.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics + St. Louis Fed

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics + St. Louis Fed

The BLS began officially tracking work stoppage data in 1947, so I went out a couple of years to 1949 to allow the data to mature. By 1949, the G.I. Bill was five years old, the wartime economy had come to an end and the country was in a brief recession. Unemployment peaked during this year as well.

Workers expressed their displeasure with 262 work stoppages involving 2.5 million workers, which was 4.23% of the workforce at the time.

Fast forward to 1968, one of the most tumultuous times in American history. 362 work stoppages involving 1.8 million workers, or 2.3% of the workforce.

There were 44 stoppages involving 184,000 workers, or .15% of the workforce in 1990.

23 stoppages in 2022 involving 120,000 workers, or .07% of the workforce.

And so far this year, we have ~325,000 workers out on strike in 21 separate actions; .19% of the workforce.

During times of economic distress, labor has wielded the power of the strike to reckon with the corporate class to varying degrees of success. If we go back further than our 1949 start date, labor actions in the United States were even more severe, and so was the response to them. But rather than litigate the rise of organized labor from the mid 19th Century through the Depression, I think it’s more instructive to look at working class struggles in the postwar period when the United States emerged as the hegemonic power in the world.

One of the reasons we went on such a deep dive of socialism was to call attention to the divide between organized labor and leftist political movements. Nowhere was this divide more extreme than in the United States.

Take the story of Eugene Debs, for example. Debs was perhaps the greatest champion of union labor in U.S. history. (There will be labor historians that likely take exception with this statement, but I’ll stand by it until scolded otherwise.) Though Debs became the face of the Socialist Party, running for president four times, he never abandoned his roots as a labor organizer. Yet, even though he was beloved by the working class, he was unable to bridge the divide between trade unions and industrial unions, let alone the political class. We even covered how it was Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) who ultimately sold Debs and the socialists down the river to split the labor vote in Debs’ last two bids for the presidency.

But the U.S. isn’t alone in this distinction. Fissures between the left political class and organized labor were commonplace throughout Europe as well. And that strikes at the heart of the thesis here today.

Capitalism & Unions Support One Another

If we think about union struggles in the U.S., they have always been in sync with capitalism. In fact, they very much support one another.

Hear me out. Think about what the unions today are fighting for. Pretty fundamental stuff: Better benefits, higher wages, more paid time off, paid family leave, and improved working conditions, generally. When the UAW yells about the billions spent in stock buybacks, it’s framed as greedy and wasteful because those funds could otherwise be used to incentivize workers. They even go so far as to say clearly that those very profits are the result of the workers’ labor, not the executives or the shareholders. Then, the corporate mouthpieces are trained to respond like General Motors (GM) CEO Mary Barra, who had this to say:

“When you talk about executive comp, for instance my comp, over 92% of the compensation is performance linked. In addition to the 20% increases in salaries that we have on the table right now, our employees have been enjoying profit sharing for several years. And through the last few years it’s been record profit sharing. And so the way that General Motors is set up is that when the company does well everyone does well.”

There’s two parts to her response. The first is the idea of executive compensation based on incentives. So let’s talk comp.

In 2022, her base salary was $2 million. But her compensation was $29 million. She has raked in over $200 million since 2014. (Over at Ford, by the way, things are pretty much the same. Ford CEO James Farley made about $21 million in 2022. In case you were wondering, he’s the late Chris Farley’s cousin.)

Anyway, when these CEOs talk about incentives, they’re talking about share price.

That brings us to the other part of the equation. The best way to increase shareholder value and stock price these days: Stock buybacks.

In fact, the GM board authorized the company to increase the buyback threshold in 2022 from $3.5 billion to $5 billion. So not only did car prices increase by upwards of 35% after the pandemic, and not only did corporations take in money from the federal government to get through the pandemic, they used a bunch of this money to buy back shares. That’s what she means by performance.

Now, the other half of the equation is the profit sharing piece that the employees received. GM was pretty boastful in 2021 that their profit sharing plan put an extra $12,000/check on average into the pocket of every GM auto worker. Not bad. All told, it was about $500 million spread among the employees, who average about $80,000 in compensation normally. According to the Social Security Administration, the average national wage index per person in 2021 was about $60,000. So GM’s perspective is, ‘We’re paying more than the national average and you got a piece of the profit. What’s your problem?’

And there are a fair number of Americans who live without union protections who look at that stance and kind of agree. But let’s dig just below the surface here. That $500 million split among the workers in a profit sharing plan sounds great.

Now frame it this way: $500 million spread among 40,000 eligible workers based on profits against $27 million allocated for one person based on stock performance.

I’ll frame it another way: In the same financial period, GM posted a $17 billion profit. So the profit sharing that went to the employees was about 3% of the total profits, whereas the shareholder buyback was around 30%.

That’s why the UAW is calling bullshit, and so should you. So should everyone. But that’s still not the larger point.

Level-Setting Definitions

Let’s level-set quickly on a few definitions. Having never been in a union myself, these are concepts that I don’t live with and therefore take for granted. But they’re really important to nail down, though I suspect they’ll be pretty familiar.

Briefly, let’s refresh from our labor union essay and socialism series on just a handful of concepts. Trade union, industrial union, collective bargaining and right to work.

Trade unions are often referred to as craft unions. They are specific to a particular job or vertical in an industry. Ironworkers, teachers, cops, actors, auto workers. If you belong to one of these unions, whether you’re in the physical trades or the service sector, you’re part of a trade union.

Industrial unions have classically been defined as any and all workers, at least in the Marxist tradition. Members of an entire class would be eligible. It evolved in many countries to incorporate workers within an entire industry. Teamsters are a great example. Originally freight drivers, teamster unions grew to incorporate different aspects of freight and logistics like warehouse workers.

There are also public sector trade unions to represent government employees and credit unions, which were designed to manage the financial affairs first of large corporations, but evolved to take in members of designated groups to own the institution itself.

But when we think about organized labor, strike and work stoppage actions and negotiating benefits and pay raises, we’re typically talking about unions that represent specific trades. At least, that’s how it’s conflated in the media.

Collective bargaining is another term that is thrown around casually, but it also deserves a little unpacking for context. For example, nearly 2/3 of the workforce in the United States is technically allowed to pursue collective bargaining agreements. That’s where employees can join a group to bargain with corporate ownership for compensation and benefits. This process was guaranteed to all American workers by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) Act of 1935, part of the suite of programs that came into existence during the Depression.

So, why don’t we all collectively bargain with the owner class in this way? Because it’s a feature of union membership. The idea was to establish hard and fast rules for employees to meet and determine whether or not to form a union for such purposes. In theory, these meetings and decisions would be unfettered by ownership. Along the way, of course, the capitalist class pushed back on this; specifically in 1947 with the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act. Dipping back into our labor essay as a refresher, from the book State of the Union by Nelson Lichtenstein:

“The new law codified the union-hostile status quo in the cotton South and the entrepreneurial Southwest, especially after most states in those regions took advantage of Section 14b to ban the union shop and enact ‘right-to-work’ statutes. Such laws had a two-fold purpose: they kept the unions financially and organizationally fragile, but even more important they represented an ideological onslaught of the first order, because now the ‘rights’ of anti-union workers were given the same moral weight as those loyal to the union idea. Likewise, another Taft-Hartley revision of the Wagner-era labor law gave to employers the right to ‘free speech’ during NLRB elections. Given the employment power wielded by management, such anti-union speech was normally indistinguishable from intimidation. But once again the real issue was not the technical definition of ‘speech,’ but the devaluation of the idea of worker-self organization independent of managerial influence.”

Taft-Hartley gave corporations the ability to create hostile organizing conditions. It protected all forms of intimidation and smear campaigns. At the depth of the Great Depression, when the NLRB Act was introduced, union membership hovered around 12%. By the time Taft-Hartley was passed, about 1/3 of U.S. workers were in a union. Since then, it’s been on a steady and precipitous decline. Union membership in the United States is now around 10%, which is below where we were in the Great Depression just prior to the NLRB coming into existence.

That’s how far we’ve fallen and why I cannot in good conscience call what’s happening today a “movement.” 1949. 1/3 of all Americans were in a union. The United States was about to go on a 25 year economic tear with workers participating in the upside. 262 work stoppages involving 2.5 million workers, more than 4% of the entire workforce. That’s a movement.

Going from .07% to .19% is an uptick. It’s not even a trend. It’s a rounding error. Contrast that with the breathless media coverage on both sides of the political aisle. Liberal media, mostly in support of the workers in a way that we admittedly haven’t seen in quite a while. Conservative media is basically saying it’s the end of the world. And usually, the truth can be found somewhere in the middle. Except the real truth isn’t even on this same spectrum.

Again, think about the gains workers seek. Increased pay to cover cost of living adjustments. Fairer wages in the face of landmark corporate profits. Better benefits like paid time off, paid family leave, subsidized child care, better health benefits. Best case scenario, the .19% of workers asking for these things get everything they want. And maybe it encourages 10 or 20k more workers to do the same thing. That’s not a movement. That’s a blip. When workers in Denmark ask for more, it’s more than blip because 67% of workers in Denmark belong to a union. In Sweden, it’s 70%. Finland, 74%.

(But hold on a sec. What about the French people you love so much? Only 8% of the workforce in France is unionized.)

True, but 98% are covered by collective bargaining, and when the French workers don’t get their way, they organize quickly, take to the streets and literally burn shit to the ground. The workers in France created a different culture. They never stopped stoking the flames of a revolutionary labor movement.

But we’re just so different. Special.

Let’s stay on the culture question for a moment because it gets us into a conversation about American exceptionalism, innovation, freedom and entrepreneurship.

As we’ve said a thousand times before, the corporate class likes to point to innovation and entrepreneurship as the reason we can’t have unions, or taxes, or regulations—basically, anything that would crush the entrepreneurial spirit of American businesspeople. It’s horseshit. Pharmaceutical drugs, chemicals, the internet, renewable energy, artificial intelligence, weapons of mass destruction: All built by public investment and government programs and spread to the private sector for iteration and expansion, not innovation and origination.

That said, I don’t want to get too off topic from the original thesis.

There is no labor movement in the United States. The benefits sought by the working class are derivative of the capitalist system. They’re elements of the wage slavery that Mikhail Bakunin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Rosa Luxemburg pointed out over a hundred years ago. When Marxists and syndicalists argued for a dictatorship of the proletariat, it didn’t imply violence in the way we associate with the word dictatorship these days. It literally just meant control and ownership.

It doesn’t mean that the UAW isn’t fighting for a more fair and just outcome within the capitalist system. It is. But it’s wild to think that even victory in this fight only further serves to calcify the rules of engagement between the classes. I’m not saying they shouldn’t fight the good fight.

Moreover, the WGA and SAG have added an important layer to the narrative by fighting for the creative economy. Beyond the fact that they make up more than half of striking workers, the high profile nature of their work keeps labor in the public eye. The flip side—and by flip side, I don’t mean downside—is that a creative work stoppage affects the creators, the companies they work for, to be sure, and the shareholders of these companies. It doesn’t bring the supply chain to a grinding halt, increase prices at the pump or cause pain in a way that makes average Americans uncomfortable. So, in many ways, that makes their struggle all the more courageous. They’re fighting for something much bigger than themselves in a sacrificial way.

If every healthcare worker, educator and sanitation worker simultaneously walked off the job in protest of the capitalist class, it would signify a change. A movement. When a fraction of a fraction of the workforce has the guts to stand up against the corporate class, they might stand to gain a little, but they risk a lot more in the process.

So what’s my point?

The point is that I have a greater appreciation for Marxist theory of class struggle and labor than ever before. At the same time, I cannot help but be pragmatic and to state the obvious. Here’s where we can go back to the lessons from our socialism series.

A great number of things have to come together to create the conditions for revolution. And I think it’s fair to say that the working class is a fundamental part of the revolutionary equation, even today. There’s also the legal system; look at how the Federalist Society has torn apart the courts. What’s taught in schools; PragerU is being added to curriculums and we’re back to banning books.

We need organized interest groups in disparate regions working collaboratively toward a stated purpose. Shared messaging. Political movements. Social movements. Protests or outright riots. Then there’s the all-important catalyzing and potentially catastrophic event that threads them all together with the hope that there’s a like-minded bureaucratic apparatus capable of seizing power from below to implement reform and manage systems.

But none of this happens without class consciousness.

And how do you raise the consciousness of a class that doesn’t know that it exists?

Working class used to be an identity. Now it’s a talking point and historical reference. What defines “working class?” Household income, occupation? Perhaps the worst lie ever told is the so-called American Dream because it’s convinced millions of wage slaves that if they hustle, keep grinding, 24/7/365, they can break out in the land of opportunity and get what’s theirs. Day job. Uber driver at night. Weekend influencer. Keep hustling. Keep grinding. Just don’t call yourself working class because that’s your grandparents. And don’t let the woke agenda of the left keep you from reaching your dreams.

Make your bed. Hit the gym.

Work hard. Play hard.

Hustle. Grind.

Get yours.

Keep yours.

And close the door behind you while we distract the others.

CEOs making 400 times the average employee?

I heard schools are putting litter boxes in bathrooms for kids who identify as cats.

Inflation due to corporate greed and price gouging?

Yo, Tucker Carlson said Barack Obama is gay.

Corporations invested in student loan programs lobby to have the courts reverse debt cancellation?

Everyone knows mermaids are white!

Divert.

Distract.

Repeat.

The American Dream has poisoned class consciousness. 13% of the workforce in the new economy works remotely. 29% have hybrid positions. 36% of the workforce is considered “independent,” which is comprised of gig workers, freelancers, contract workers and part-timers. 61% of Americans say they’re living paycheck to paycheck.

The capitalist system has sliced and diced us and broken us apart.

The other feature of the capitalist system is even more underhanded. Capitalism is like a mysterious conductor. It has no face. No name. But it has its own rhythm. It knows when we have just a little too much in our wallets, so it knows when to pick our pockets.

And it knows when we’re up against a wall, so maybe unemployment lasts a few weeks longer this time. Maybe there’s a check in the mail. A pause on debt collecting.

So you can get back on your feet.

Get back to the hustle.

Back to the grind.

It’s always been that way. An election about to swing one way during a recession, then all of a sudden a brief recovery. A bumper crop. Government contracts come through. Maybe a tax cut! But not for you, for them. The owners. The employers. The job creators. Hang on just long enough, and it’ll trickle down to you.

What to do, what to do.

Even if all of the conditions required to ignite a revolution were in place, who would revolt if the masses are separated both physically and spiritually? Gig workers unite?! Freelancers take to the streets!

Once again: A class cannot gain consciousness if it doesn’t even know it exists.

The Biden NLRB recently made the most historic ruling since Taft-Hartley, and that’s not an exaggeration. Here’s a summary from the NLRB website:

Under the new framework, when a union requests recognition on the basis that a majority of employees in an appropriate bargaining unit have designated the union as their representative, an employer must either recognize and bargain with the union or promptly file an RM petition seeking an election. However, if an employer who seeks an election commits any unfair labor practice that would require setting aside the election, the petition will be dismissed, and—rather than re-running the election—the Board will order the employer to recognize and bargain with the union.

This is one of the most significant developments in American labor in my lifetime, to be sure. It’s more than a warning shot. It’s a blow to any corporation that attempts to shut down union organizing attempts. Of course, a decision from this Biden appointed board can just as easily be reversed under a new GOP administration, and I can pretty much guarantee that it would be immediate. So it’s temporary, but meaningful nonetheless.

This ruling. Actors and writers drawing outsized attention to worker grievances and inequality. The masterful job the UAW is doing to force the auto makers’ hands. The left is finally showing some level of solidarity with union organizers. It’s all good stuff. But remember. At .19%, you cannot call it a movement. Capitalism is still winning going away. Moreover, a victory within the system is still an acknowledgement of a fixed power dynamic.

So what else is out there? I know there are tons of Unf*ckers who share my enthusiasm for Professor Wolff and the Democracy at Work organization. I’m providing a link to the new Democracy at Work website that has information on the concept of worker cooperatives, a huge part of his agenda to transform the American work culture.

The big question is, can worker cooperatives happen here?

I believe so.

The world’s largest cooperative is The Mondragon Corporation of Spain. 81,000 employees. $14.5 billion in revenue. Here’s an excerpt from a New Yorker article about how Mondragon defies all capitalist narratives and explanations:

“Worker-owned coöperatives are often considered both idealistic and inefficient; the model is seen as suitable mainly for upscale grocery stores or boutique bakeries in progressive towns. At a 2019 conference, the economist Larry Summers characterized co-ops as intrinsically sleepy and short-sighted. ‘When you put workers in charge of firms and you give them substantial control over the firms,’ he said, ‘the one thing you do not get is expansion. You get more for the people who are already there.’

“And yet, Mondragon is not a sleepy grocery store. Its collection of co-ops employs around eighty thousand people, and seventy-six per cent of those who work in manufacturing co-ops are owners. One makes bicycles at an industrial scale; others make elevators or produce huge industrial machines used in the production of jet engines, rockets, and wind turbines. Mondragon’s businesses include schools, a large grocery chain, a catering company, fourteen technology R. & D. centers, and a McKinsey-like consulting firm. In 2021, the network brought in more than eleven billion euros in revenue. The collective enforces five hundred and five types of patents and employs about twenty-four hundred full-time researchers. It also owns subsidiaries in countries including China, Germany, and Mexico, and competes effectively in international markets, winning contracts from firms such as General Electric and Blue Origin. The odds are good that key elements of something within a hundred feet of you—an espresso maker, a gas grill, a car—were made at Mondragon.”

In fairness, no corporation—even Mondragon—exists without controversy. In fact, one of the biggest challenges they’ve recently faced is an increase in CEO pay relative to the lowest Mondragon worker. It was quite a scandal. A new policy allows CEOs pay of...Allow them to paid… God I can barely say it…

You got this. What is it? 20 times? 50 times? 100?

Six. Seis. 6.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, CEO pay in America has “skyrocketed 1,460% since 1978” and that “CEOs were paid 399 times as much as a typical worker in 2021.” Mondragon members tortured themselves over whether to bump the CEO pay ceiling from 5.5 to 6 times the lowest paid worker in the entire cooperative.

Worker cooperatives exist in the United States. In fact, there are more than 600 of them. Again, a rounding error, but a start. Not only do they work, they can develop alongside unions and in many cases, support one another.

Let’s thread together a few different narratives from the work we’ve done together. This is different from the neoliberal New Democrat proposals under Bill Clinton that attempted to turn workers into entrepreneurs through capitalist debt models. This is different from trade unions fighting for crumbs that fall from the capitalist table. Millions of workers in other countries are worker-owners. In the U.S., it’s thousands.

Now think about our sustainability essays. Cooperatives tend to be more sustainability-minded as well. But, to get from thousands to millions of workers requires a worker revolution.

And now, think about the conditions required to promote and sustain a revolution, a permanent revolution, as Leon Trotsky would say. Generative AI is a catalyzing event that is transforming work. Millennials and Gen Z are more socially conscious and digitally savvy. Tens of millions of Boomers are exiting the workforce as we speak. (Buh-bye!) Inequality is reaching a tipping point.

But we also know from Robert Owen’s New Harmony experiment—along with countless examples of what happens to the worker mindset during recessions—that what American workers want more than anything is a steady paycheck, a secure retirement, healthcare coverage and a future for themselves and their families. But grinding against this need, somewhere deep down and buried in our DNA is something else: the palpable notion of the American Dream. That’s part of our duality that causes us to fight our natural instincts and ultimately settle for what’s handed to us.

To be a worker with comfort or part of the owner class? That’s the tension that has been as of yet unresolvable. The cooperative model says, “why not both.”

Having this conversation does something else. It shifts the narrative focus and, in doing so, raises consciousness. Americans may never again see themselves as working class. But that doesn’t mean we can’t have class consciousness. Food for thought.

Support the unions.

Raise consciousness.

Don’t just fight the power, be the power.

Here endeth the lesson.

Image Sources

- “WGA Strike 6.21.2023 065” by ufcw770 is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Changes were made.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.