Unf*cking Flashback: The Assange Problem.

Time is Running Out to Salvage Press Freedom.

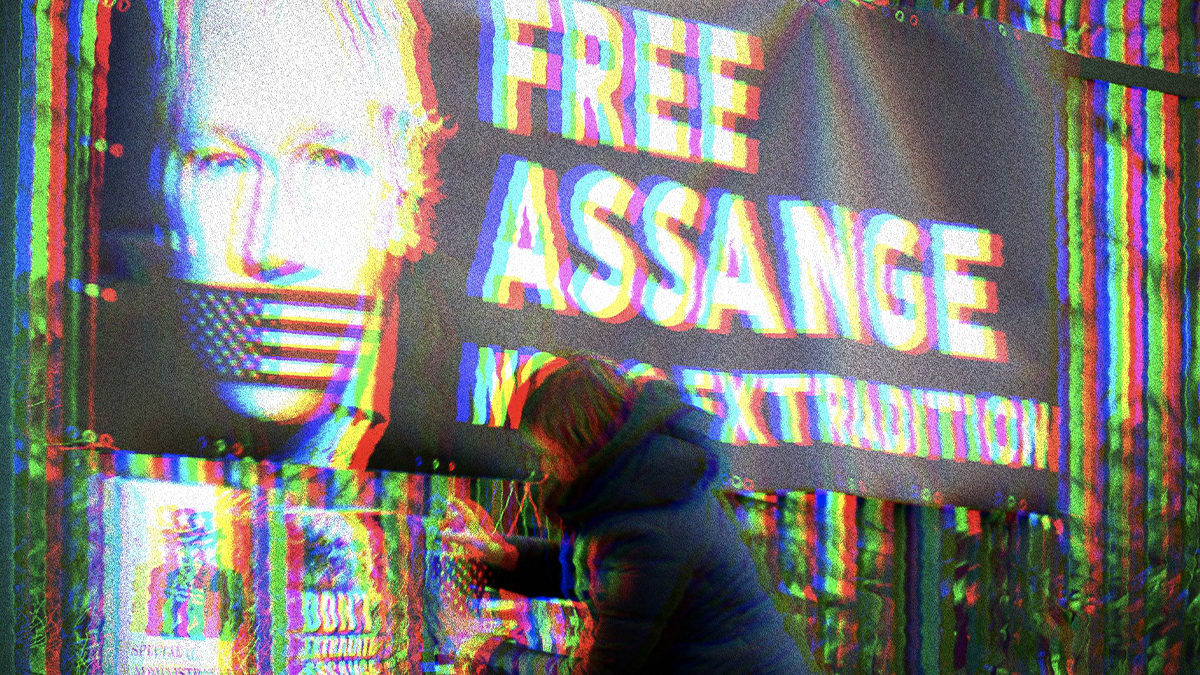

Image Description: Glitchy photo of a banner with a photo of Julian Assange with American Flag tape over his mouth. Banner text says, ‘Free Assange. No U.S. Extradition.’ Below the banner a woman is adding another pro-Assange poster.

Image Description: Glitchy photo of a banner with a photo of Julian Assange with American Flag tape over his mouth. Banner text says, ‘Free Assange. No U.S. Extradition.’ Below the banner a woman is adding another pro-Assange poster.

[An update from Max, 6/26/23] Hey Unf*ckers. This essay updates the Assange piece we released a while back. It’s possible that by the time you read this, there will have been movement on his case. If not, it seems likely that his extradition to the United States is imminent. So I’ve updated the essay with some new thoughts and generally cleaned up the text; it’s very similar, almost a re-release of the original, just tighter and more focused. Either way, it’s a good refresher considering how much the Espionage Act is in the news these days. But mostly it’s a necessary reminder of what’s at stake.

Collateral Murder

Julian Assange might be out of options. After a UK judge denied a final appeal to turn down an extradition request from the United States, Assange has only the European Court of Human Rights to appeal to. And it’s unknown whether his case will be heard, or if this venue even has the authority to stop the extradition process. A while back, we did a full essay on Assange, so we’re going to run back some details from that essay as a refresher. But, a lot has changed in the past several months, and it’s quite possible that Julian Assange may never again see the light of day.

Assange is a complicated figure, personally and historically. And he evokes pretty strong reactions. Mostly, though, we don’t think about him at all. With the exception of occasional reports whenever there’s an update on his charges or extradition attempts, Assange has been sort of back burnered. Considering the stakes at play for the U.S. media, this should be surprising, or even troubling.

The story of Julian Assange cannot be told without viewing the leaked footage of U.S. Apache helicopters gunning down unarmed civilians in Iraq. The footage is difficult to watch. The video was obtained by WikiLeaks on April 5, 2010. Here’s a timestamped summary of what we’ll be covering:

2:45–3:00

A handful of civilian men were walking down a desolate street in Iraq with an Apache helicopter hovering overhead. Before the gunfire, a dispatch looked for clearance to shoot, saying it had confirmation one of the men had an RPG.

3:34–3:44

It wasn’t an RPG. It was most likely a camera, as among the murdered civilians were two Reuters reporters. This explains why the men would have been walking so casually and undeterred by the presence of a U.S. helicopter hovering above. As the men lay in pools of blood on the street, the U.S. gunmen carried on radio chatter and called in ground support.

7:56–8:19 + 10:05–10:08

A few minutes later, a civilian van pulls up to the scene. Two samaritans jump out of the van and attempt to assist the only surviving member of the group.

15:21–15:30

They, too, were gunned down in a hailstorm of bullets from the Apache helicopter. As the ground support arrived and began to take stock of the situation, it quickly became clear that the mass casualties were civilians, so the helicopter crew repeated the claim that there was an RPG.

17:31–17:42

A member of the ground support then calls for assistance to help the wounded. There were children in the back of the van.

As we now know, Wikileaks obtained this footage dubbed “Collateral Murder” and a massive trove of other documents from private Chelsea Manning. Over several months Manning uploaded hundreds of thousands of documents from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, diplomatic cables and two highly sensitive videos, Collateral Murder and another that purportedly shows the slaughter of Afghan citizens. The latter video has never surfaced.

WikiLeaks followed up by publishing the so-called “Iraq War Logs” and “Afghan War Diary,” lifting the veil on America’s bloody post-9/11 wars, exposing civilian casualties and extrajudicial killings.

Also released were hundreds of thousands of State Department cables and secret documents, many marked “confidential,” as opposed to “secret” or “top secret”—the highest level of classification. The documents also revealed evidence that U.S. forces killed 10 Iraqi civilians, including an infant, and called in an airstrike to destroy the evidence. According to a McClatchy report at the time: “all the dead had been handcuffed and shot in the head.”

This was a game-changer. Some of the most decorated media outlets in the world not only collaborated with WikiLeaks—including The New York Times and The Guardian—but leveraged the cache to contextualize America’s so-called “War on Terror”—and continue to do so today.

Land of the Free

We like to think of ourselves as the land of the free. Press freedoms, protected speech, First Amendment rights are crucial to our identity as a nation, and as a people. We’ve traditionally been wary of an overzealous government seeking to take away such freedoms, but then balk at the strangest of times, as in the case of Assange. Now I get it, for Americans, Assange is sort of a tricky character, largely because of the narrative that surrounds him, regardless of how this narrative was crafted or by whom.

Part of the rub about Wikileaks is that it’s indiscriminate. So, depending upon where you land on the political spectrum, it may have contributed to supporting your personal thesis on politics or assaulted it. Plus, Assange isn’t one of us. He’s Australian, but looks more like a washed out villain from Die Hard.

He’s also an unusual man who might have social issues, according to those who know him personally. Which is to say, he has difficulty relating to people in customary ways and misses certain social cues. Perhaps that’s why we collectively engage in schadenfreude at the sight of a disheveled Assange being dragged into custody.

For years now, we have mused about this once towering shadowy figure being reduced to a skateboarding weirdo holed up in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. Time and selective national amnesia tend to muddy events in our minds, and the further out of sight the man was, the more of a human interest story he became instead of a human rights story. We laughed at his long hair and scraggly beard. Casually discarded him over rape allegations, which we’ll address, that were never resolved properly in court but certainly decided in the court of public opinion. Much in the same way that Chelsea Manning’s transition was treated as a sign of mental illness that surely contributed to her desire to screw over her country, Assange has been cast aside as an oddity who might have once been useful, but turned nuisance or perhaps even traitor.

In many ways, the fight against Assange represents the actions of an Empire against the most important of our rights as Americans, and globally as citizens. You don’t have to like Julian Assange, or even care about any of the information he exposed, to understand the importance of a free press in any democracy. At its best, a free press exposes the most flagrant violations to our rights as citizens and unmasks those who would do us harm through the mechanisms of state and corporate power. Without a true fourth estate, we are left exposed to an increasingly militaristic state that, left unchecked, will endeavor to clamp down on dissent in such a way that it chills the press, prevents the flow of information from whistleblowers and turns all media into mouthpieces for the state.

As a practical matter, we’re almost there. The Patriot Act, new provisions introduced under Obama’s NDAA, expanded use of the FISA courts for domestic affairs, the NSA surveillance program exposed by Ed Snowden, and cooperation with corporate entities from social media giants to cable companies have all contributed to the steady erosion of privacy and our rights.

Your personal data? It’s gone. Sold a thousand times over. Unless you live in the woods without a smartphone or tech of any kind, you’re on someone’s radar and exist in databases all over the world. Our steady acquiescence to losing privacy has lulled us into a false sense of security and turned our priorities upside down. We’re so far removed from the concept of true liberty and free speech and our constitutional protections that we’ve blurred the lines between our rights and the rights of the state. Think about it. We have willingly handed our data, our digital lives and information over to corporate entities that work collaboratively with this and other governments, and yet we defend the government’s absolute right to secrecy and are willing to turn a blind eye to those who expose corporate and government secrets, no matter how nefarious they may be.

To really break this down, let’s start by going through a list of some of the more prominent items that Wikileaks brought to light.

Let’s start with the present day and talk quickly about where Julian Assange is right now, because the situation remains both extraordinarily complex and extremely simple at the same time. The complexity of his situation is revealed through both what Assange accomplished in a relatively short period of time at the helm of Wikileaks and the incredible lengths several governments, but mostly ours, have gone through to silence him.

As of this moment, he is still being detained in the UK and just exhausted his final appeal to prevent extradition to the United States to stand trial under espionage charges levied by the Trump Administration. The obvious question is, why doesn’t Biden simply reverse course on Pompeo’s charges? Here’s the simple and frustrating answer. He could. He just won’t.

The UK could theoretically release him instead of holding him prisoner under what the UN has called extreme and dangerous conditions. He could go free today and seek refuge in one of the many countries that has offered him sanctuary, as Obrador in Mexico did. Likewise, the Biden administration has the complete power and authority to simply dismiss the charges against him. The rape charges against him in Sweden, a complicating and murky factor that we’ll cover in a moment, have been dropped. The UK has no reasonable basis to continue holding him, particularly because they are under no obligation to extradite someone on political charges.

The U.S., as we’ll also cover, risks trampling on the Constitution itself if it doesn’t drop the charges against him. Very simple answers to an extremely complicated situation. I can only assume at this point that it’s a matter of pride, because the regimes after Assange have all painted themselves into a corner where the obvious answer is to drop it and let him go, which would mean admitting we messed up.

Assange the man has been politicized because of the effect that his work has had at varying points. Right? To some, he’s an irresponsible liberal who undermined the Bush administration at a time of war. To others, he’s a Trump ally and Russian operative who swung the U.S. election in favor of Republicans. The Obama administration pulled the threads all around him, indicting the whistleblowers he worked with, but stopped short of coming after him personally. Though, as we’ll see, perhaps the biggest villain in this story—despite the ludicrous level of charges brought against Assange by Pompeo, is the Obama administration. Let’s go back.

The Media Gravy Train

Beyond Collateral Murder, which is damning and horrifying enough to justify the existence of Wikileaks, it’s important to review just how substantial the impact of Wikileaks has been. Arguably the biggest stories of the past decade had Wikileaks’ fingerprints on it, and for a while, most major news outlets in the world were all too happy to ride the gravy train.

Hundreds of thousands of documents were released in the Afghan War Logs, and tens of thousands more were uploaded to Wikileaks and disseminated to the press in the Iraq War Logs. Through the war logs dump, which include Syria and Yemen, it was revealed that the United States was essentially adrift on all fronts. Dispatches of confused double dealings and failed diplomatic efforts were mixed among thousands of documents showing the complete absence of a coordinated plan, let alone exit strategy, in any region. The New York Times, The Guardian, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, El Pais, The Intercept, dozens of alternative outlets, all worked with Wikileaks and dedicated resources to sifting through the treasure trove of documents. Major outlets had a field day with the releases, particularly on the left, because it exposed the failures of the Bush doctrine.

But it didn’t end there. Through Wikileaks, we discovered the secret dealings of the Obama administration’s plan to secure the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a clandestine effort to create a global trade agreement that would paint China into a corner and allow the U.S. to more easily access and exploit cheap labor in developing countries, among other things. Some of the cables are credited with inspiring the Arab Spring. The DNC Database leak exposed the coordinated attempt to smear the Sanders’ campaign and turn the tide of the Democratic primaries. And, of course, the Podesta emails exposed the Clinton Foundation ties to Saudi Arabia, Hillary Clinton’s speaking engagement fees to Goldman Sachs and assurances to bankers that they would be at the table in drawing financial policy in her administration. Or the fact that she had access to questions ahead of the primary debates.

These are just a few of the major highlights, and like I said, depending upon which side of the aisle you’re seated, you might have a serious axe to grind with some of this information being made public. But that’s hardly the point.

We’ll get to the essential point of the thesis when we talk about the charges that have been levied against Assange, and why prosecuting him on this basis is a disaster on so many levels. But first, I think it’s important to run through the myths that surround Assange and the arguments against him that fail to hold water.

Quickly, there’s the careless allegation that he’s a traitor. Nothing speaks more to our American exceptionalism view of the world than this charge. First off, he’s not American. He’s Australian. And he’s fairly agnostic in terms of his subject matter. Few major players on the world stage have escaped embarrassment from his leaks, though in typical American fashion, we just assume it’s all about us. Even still, the term itself—traitor—applies specifically to a citizen who provides aid and comfort to the enemy during a time of war.

Then, there’s the argument that no one has a right to classified information. It’s classified for a reason. This is a great debate, and one that I wish the country would have out loud. The overclassification of documents is out of control. It’s also illegal, but that rarely matters to those in power. They make the laws, so they get to break them.

But most of the reporting that came from the war logs, as an example, were diplomatic cables not covered by classified status. More to the point, it strikes at the heart of what the public deserves to know. The Pentagon Papers is the classic example of whistleblowing and leaking classified information. Yes, Daniel Ellsberg was brought up on charges of espionage, but the charges were dropped mostly because the government knew then that it was walking a tightrope called the First Amendment.

If you think about what it is to be the fourth estate—to be part of a free press—it means that you are exactly at odds with the power structure. Your job is to set information free. The caveat, which we’ll talk about, is whether you have a process in place to determine whether the information you’ve obtained would pose imminent danger to anyone if revealed. The bottom line is that the very nature of journalism is to source these materials and make a call as to whether the public has a right to know.

Did the public have the right to know that we murdered civilians in Iraq then tried to cover it up? Did Reuters have a right to know why two of their reporters were gunned down in cold blood by U.S. forces? Did Americans have the right to know that our government had no plan to effectively litigate or extract ourselves from conflicts that sent our sons and daughters to die and cost taxpayers trillions of dollars? Hopefully, the answers are self-evident.

Then there are the personal attacks. It’s a classic technique. When you can’t stand on the facts, drag your opponent through the mud. Victim blaming government style. Assange is untidy. He smells. He’s vulgar. He’s not following the rules we made up in newsrooms that routinely kowtow to power and literally hold stories back when requested by the powers that be. He’s a liberal. He’s a conservative. He’s a narcissist. And, the most damaging accusation that deserves our attention: he’s a rapist.

Rape Allegations

Remember that Assange was originally being held in the UK because of pending rape charges against him in Sweden. In many ways, this was the end for Assange, because the allegations alone made him instantly unlikable and difficult to defend. To be clear, one has nothing to do with the other, but the court of public opinion doesn’t allow for such nuance; and, frankly, if he’s a rapist, then he can go fuck himself and rot in prison for that. But, we have to be strong enough to see clearly that it has no bearing on the validity of Wikileaks and the need to protect it and its founder from charges that would undermine democracy.

One of the most productive phenomenons today is the movement toward believing the victim. A reversal of ‘innocent until proven guilty,’ but in a way that actually benefits society. So many of us, particularly those in progressive circles, were caught in a trap of defending Assange for his work, but condemning him for his behavior. The challenge was in separating the two. But the harder question is whether they should have been separated at all. This is the tough talk we need to have, so let’s walk carefully through the timeline.

First off, Assange has never been formally charged with rape. In Sweden, the laws work a little differently than in the U.S., and sexual misconduct allegations are actually taken more seriously. The allegation was that he had risky, unprotected but consensual sex with two different partners who grew concerned that Assange might have infected them with a sexually transmitted infection. So, they went to the police. These allegations fell under Sweden’s more stringent predatory sex laws, and so it was made public that he might have to stand for questioning.

And so, Assange waited in Sweden for more than a month to be questioned, but it never came. Neither accuser would ever submit to formally charge him with rape, as that wasn’t their specific concern. After waiting for questioning that never came, Assange ultimately left for the UK. It was after this point, and not until a Swedish prosecutor named Marianne Ny picked up the charges on her own, that Assange sought asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in the UK. So the question is, why then and why at all?

It was clear that Ny was operating under pressure from the U.S. government to find a way to hold Assange in the event they wanted to begin the extradition process to the U.S., because the Obama administration was still in the process of deciding whether or not it would pursue charges against him. This was an educated guess at the time, that we now know to be true due to reporting from The Intercept. It also makes sense, since Ny would ultimately drop the charges completely in 2017 on the day she was due to appear in Swedish court to defend her rationale for charging Assange.

Assange’s team has always maintained that they were happy to cooperate with any investigation into the rape allegations, as evidenced by his voluntary outreach to Swedish authorities for over a month after the case was first opened up and made public. The reason he refused to return to Sweden when the charges were made by the new prosecutor was because Sweden refused to promise it wouldn’t extradite him to the U.S. So, he was caught in the middle, and ultimately sought his long refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy. Does any of this clear him of any potential sexual misconduct? No. But it does clarify his behavior and demonstrate that neither the threat against him nor his refusal to return to Sweden had anything to do with the allegations, specifically.

The Espionage Act

So now, let’s be clear about the U.S. charges against Assange and what this portends for journalism. First off, the very specific charges against him, levied by the Trump administration under the Espionage Act, are that Assange tried to help Chelsea Manning create a password that would conceal her identity when downloading secret documents. They’re relying on only one specific phrase—“No luck so far,” as their only evidence. With this, they’re charging Assange under subsection 793 of the Espionage Law.

Daniel Ellsberg noted that he was personally charged with 12 counts for a possible sentence of 115 years. Assange was charged with 17 counts and 175 years, which he considered a tragedy.

Ellsberg says that, at best, perhaps he would be in violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, but the fact remains that the government still has yet to put forward any evidence other than this one phrase. And, in terms of encouraging the source to provide more information by saying, “curious eyes never run dry,” every press freedom organization on the planet recognizes this as part of source cultivation, and every credible journalist has engaged in it.

So, you can begin to see why so many international press freedom organizations, the United Nations, constitutional scholars, etc. have lambasted the United States for this charge. The curious part of the whole thing is why our own press isn’t jumping up and down and screaming from the mountaintops. We need to have a serious discussion about the state of journalism in this country because precious few outlets are mounting a full throated defense for Assange.

Maybe this is why Reporters Without Borders ranked the United States 44th on the Press Freedom Index.

And, for any member of the media still making the argument that the government has a right to demand you withhold certain information or that it has an unassailable right to classify documents, I think Chris Hedges had the best response:

He said, “You can argue that this information, like the war logs, should have remained hidden, but you can’t then call yourself a journalist.”

I’m not sure who needs to hear this, but the Espionage Act is no joke. It was never intended to be used as a cudgel against the free press. It was originally passed in 1917 in response to the war effort. In 1918, Congress passed amendments that collectively became known as the Sedition Act—which was mostly used to target anti-war critics and socialists—surprise, surprise.

Perhaps the most famous case involved Socialist Party of America founder Eugene Debs, who ran for president four consecutive times. In 1918, Debs gave a speech outside an Ohio prison where three people convicted for opposing the draft were being held. Debs was arrested two weeks later and was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He had this to say during his trial:

“I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace. If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.”

Debs ran for president yet again—this time in prison—and won nearly a million votes.

A century later, and the war against the Espionage Act is still being fought. You’re probably familiar with the names: Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, Reality Winner, John Kiriakou, Thomas Drake and Jeffrey Sterling, among others. And now, that list includes former President Donald Trump, which is about as surreal a turn of events as one could possibly imagine. We can talk Trump another day. What’s frustrating about the attention swirling around Trump’s charges is that it muddies our understanding of the Espionage Act and trumps (yes, I went there) the attention Assange so desperately needs at this moment.

You have to understand: a war on sources is a war on journalism. Without the ability to develop trusted sources, journalists lose their ability to expose wrongdoing, fraud, malfeasance—or, in recent cases—widespread surveillance and war crimes.

That’s why the indictment of Julian Assange is so important. While the ruthless Obama administration toyed with the idea of indicting Assange, it ultimately decided that it couldn’t prosecute Assange—the publisher of information—without going after media outlets that do the very same thing, such as The New York Times or Washington Post.

Yet, the Trump DOJ—which celebrated the increase in leak investigations with a press conference—indicted Assange under the Espionage Act in May 2019. Part of me is taking some joy at the thought of Trump facing jail time under the very law he casually threw at Assange. But the bigger part of me wants the Act to disappear entirely.

Not since the Pentagon Papers has the media been confronted with such an existential crisis. By indicting Assange, a publisher, not a leaker himself, the government was effectively saying any media outlet that publishes classified information can be prosecuted.

To be clear, for all those who still believe that Assange put American lives at risk. Not one report, not one single report issued by any government, NGO, organization… anyone …. has shown evidence that WikiLeaks’ releases have caused the death or persecution of a single individual globally. Can the same be said of our actions? Who is more deserving to stand trial? The publisher who released evidence of U.S. troops slaughtering two Reuters reporters and a group of civilians, including children… or the murderers themselves who tried to cover it up?

Free Julian Assange. Get rid of this stupid act.

Here endeth the lesson.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.