Understanding Socialism: A History of Socialist Thought from Beccaria to Trotsky.

This week on UNFTR we have the first in the series on socialism. After our “ISMs” refresher last week, we dip our toes into the communal water and begin the process of unpacking an economic and ideological philosophy that inspires rage on the right, hope on the left and (mostly) fear in the middle. The essay starts off with listener feedback from a call we put out on social media and YouTube. We asked listeners to explain socialism in a couple of sentences and the responses were amazing. The essay continues with examples of how socialism is portrayed in the mainstream media, some basic misconceptions and UNFTR style level-setting on key terms and definitions.

AT A GLANCE:

Image Description: A Banner that says Kill Capitalism Before It Kills You

Image Description: A Banner that says Kill Capitalism Before It Kills You

Part One: An introduction to socialism.

Summary: This week on UNFTR we have the first in the series on socialism. After our “ISMs” refresher last week, we dip our toes into the communal water and begin the process of unpacking an economic and ideological philosophy that inspires rage on the right, hope on the left and (mostly) fear in the middle. The essay starts off with listener feedback from a call we put out on social media and YouTube. We asked listeners to explain socialism in a couple of sentences and the responses were amazing. The essay continues with examples of how socialism is portrayed in the mainstream media, some basic misconceptions and UNFTR style level-setting on key terms and definitions.

Welcome to the first in our series on socialism. To do this right we have to let go of the stories we tell ourselves. Ask how things came to be. Be curious and scientific, not doctrinal or emotional.

For example, if you consider yourself aligned with socialist principles, can you step back and view the marvels a capitalist system has delivered? Can you, as a capitalist, look critically at the harm? Can we ascribe values to these observations and ask whether they reflect standard moral and ethical norms we want reflected in our society? Can we accept that ideals attempting to form a general framework for society cannot be static and must evolve and iterate?

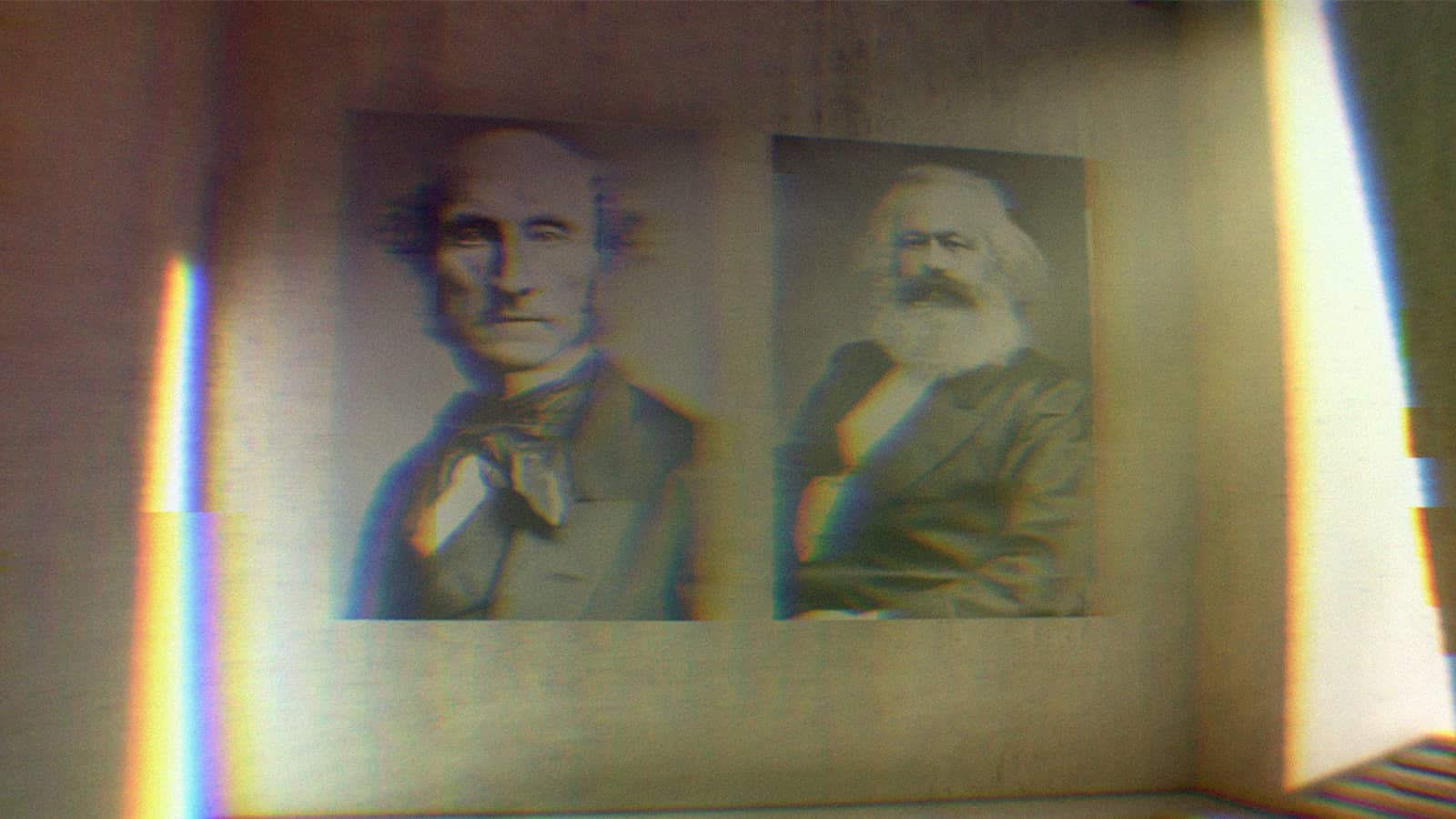

At its core, this approach is known as Hegelian dialectic, the study of opposites and constant flow. G.W.F. Hegel, who was the greatest influence on Karl Marx, was himself inspired by the work of the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus; the philosopher behind the notion that no person can step into the same river twice. The river changes. It’s in constant flow. We are as well.

The point is, you cannot evaluate a system simply by what it was intended to produce. You must also place a value upon its unintended consequences. Moreover, no system is static.

Under capitalism, the world has experienced technological innovations at a rate never before experienced in human history: medicine, communications, manufacturing, transportation. Nearly every element of society, the world over, has been impacted in a significant way under the system of capitalism. Along the way, these things have also altered the nature of capitalism. Capitalism is a different river and we, a different people. But if we’re to be true observers, we must also ask whether or not capitalism is responsible for such growth and innovation. Would society have developed in such profound ways under another system? All worthwhile questions and pathways.

This is a discussion about socialism.

So we have to establish a foundation and some definitions despite the constantly changing nature of systems. And from this foundation, we can develop key questions with the tacit agreement between us that some are unanswerable. But we can take comfort in knowing that a lack of an answer shouldn’t frustrate our quest for one. It merely recognizes the river for what it is.

The reason I began by talking about capitalism is because socialism is fundamentally a critique of capitalism. And most socialist critiques are similar in nature. The variations of socialist ideology come with the prescriptions for evolving beyond capitalism.

Much like our river analogy, the order and approach toward this series is subject to change based upon revelations through studying and feedback. But as of now, I have four essays planned in the series to try and deconstruct this amazing topic.

Part one will be level-setting. Definitions of key concepts. The history and evolution of thinking. The economics of socialism and the intersection of political, economic, social and cultural aspects of the theory. Next we’ll cover major figures of socialism from the philosophical drivers and those who added critical elements along the way, to proponents and detractors. Part three will cover the labyrinth of related systems and the myriad expressions of socialism in different regions of the world.

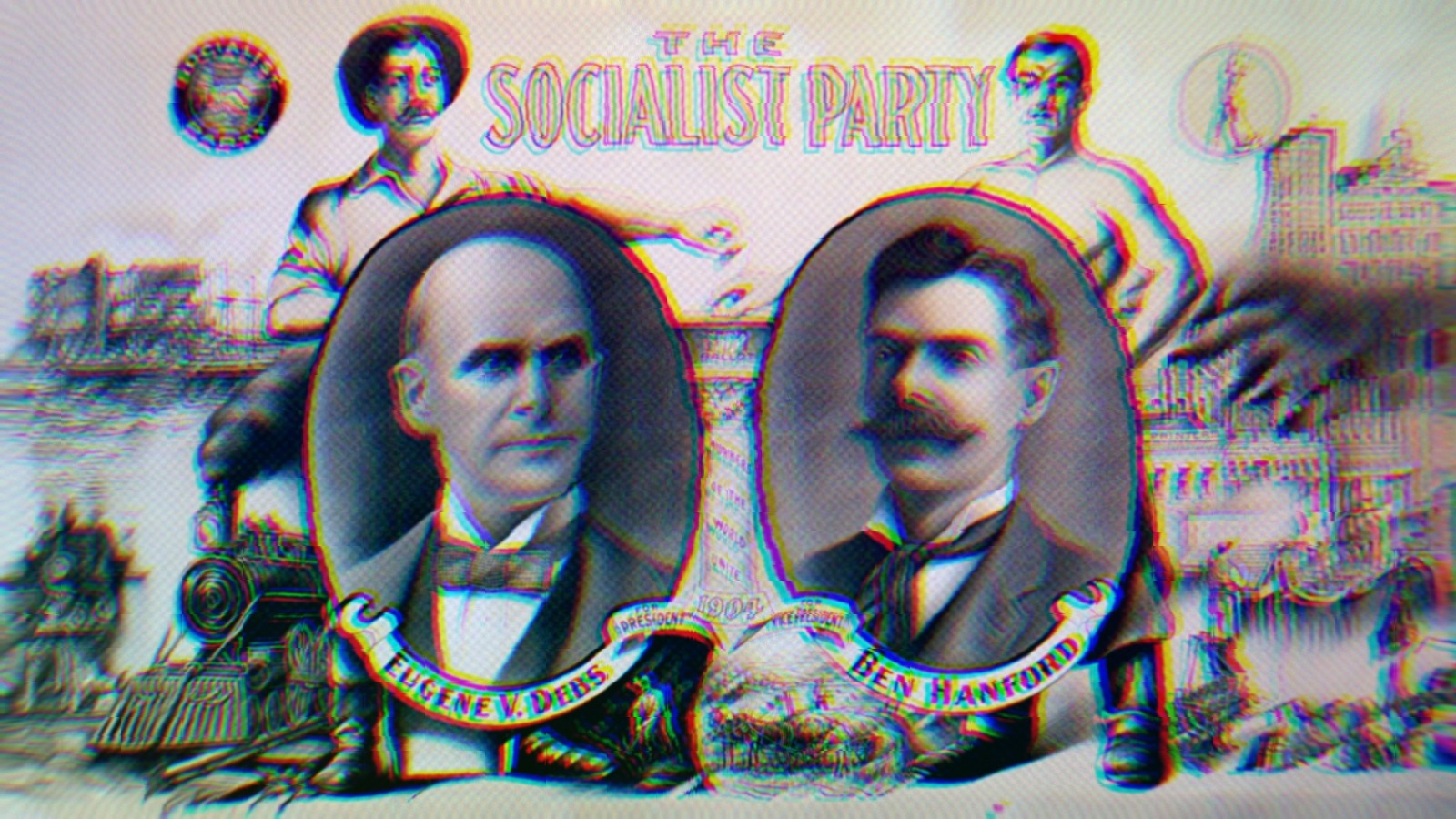

Then we’ll conclude with the American experience specifically. The influence of organized labor, significant figures, and the evolution of socialist critique in American culture.

“So let me take this opportunity to define for you, simply and straightforwardly, what democratic socialism means to me. It means building on what Franklin Delano Roosevelt said when he fought for guaranteed economic rights for all Americans. And it builds on what Martin Luther King, Jr. said in 1968 when he stated, and I quote, ‘this country has socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for the poor.’” -Bernie Sanders

Chapter One: Audience feedback and answers.

Laying this out ahead of time has given us an opportunity to be collaborative. To kick things off, I asked Unf*ckers in the Facebook group and the YouTube community to provide a basic definition of socialism as if they were explaining it to a young person. As usual, the responses were wonderful. Responses are below with names and handles used with permission from those who submitted.

Nicholas Walton: Socialism is an economic system where the government of a country nationalizes and controls all its industries.

Stephen Whitfield: Socialism is the idea of using the government to channel the profit of industry to the benefit of all the citizens that make that industry possible. A government, its citizens, and its businesses must work with one another to function properly.

Trikucian: I would explain it to my little girl as [a] government that takes money through taxes and redistributes it back to the people. Whether through infrastructure like roads, healthcare, education, or just basic welfare concepts like food and housing.

Nathan Shapiro: The equitable sharing of resources in a society. To each according to his/her needs.

Cbb Cbb: Public streets and roads and highways vs privately owned streets and roads and highways? The “comedian” Bill Maher stated something like ‘Americans love socialism, they just don’t like to call it that.’ He also remarked that ‘if you take a trip in your car, you don’t have to bring your own highway.’ Or something to that effect. I do not remember his exact words.

Alex Powers: Socialism is the abolition of the employer-employee dichotomy and a period in which the state exists not to serve the capitalist class but the working class, actively confronting the interests of the ruling class. It is the next step on the path to a moneyless, classless, stateless society.

Dan Garcia: I must cite David Pakman in explaining what I also believe: Social Democracy versus Democratic Socialism. Similar words in a different order. I feel this needs to be clarified in order to understand the misinformation and demonizing of the term, especially by the right.

Democratic Socialism is a form of Socialism where one seeks to socialize ownership of the means of production. Social Democracy is a highly regulated form of Capitalism, like we see in European and Nordic countries. Very different things.

Nelson Silva Cordeiro: I believe this can be an incredibly difficult topic to explain...but at the same time, such a simple one. Simplest in form, an elected leadership based on creating an environment, where fair and equal opportunity, and also responsibility is given to all citizens. Where the overall health of the society is put above any one’s own interests. Everyone participating keeps the possibility of a high quality of life for their communities as high as possible. Health, education, social nets etc., all offered as a right.

Mathew R. Dwyer: Socialism is recognition that some sectors are off-limits to the profit motive. Full stop.

Bob Knudsen: I think of the general philosophy of socialism as understanding and acting on the knowledge that all in society live better when top-down authoritarian systems that over-proportionate the rewards (money) to the few at the top are limited or eliminated altogether. Co-ops instead of corporations in a nutshell.

Jim Moynihan: Socialism is a term of opprobrium in America used by business interests to denigrate most expansion of government activity other than a larger defense budget.

Inigo Gonzalez: Socialism is a means of organization that prefers systems and solutions that benefit the community as a whole, over the well-being of any given individual. This generally means that said systems and solutions are designed, created, managed, and owned by the community itself, rather than by any given individual. The end result is a community more focused on equity than rapacity.

Charles Morris: A society collectively caring for its members most in need.

Bobster Jones: Fair and equal pay, healthcare, emergency services. Rich people pay more to help the poor. It’s just like Jesus taught us in Sunday School.

Rikki Mitchell: When the people own the means of production. In this day and age, I imagine that whenever a corporation needs a bailout, when subsidies go toward the oil companies or animal agriculture, etc., (using our tax dollars of course), the people would own a portion of that company. Those payouts would be used to better our communities.

Nate Bedocs: Socialism is a constructed economy that evenly distributes the wealth of a nation. This is why healthcare for all isn’t socialism, this is why any of our social safety nets (think fire, police, EMS) aren’t actually socialist policies. Please make a firm distinction that what the far right calls socialism isn’t actual socialism.

Markus Cleary: Shared a meme that said, “If a monkey hoarded more bananas than it could eat, while most of the other monkeys starved, scientists would study that monkey to figure out what was wrong with it. When humans do it, we put them on the cover of Forbes.”

Karyl Hebel: Socialism, to me, means everyone should be equal before the law, that taxation should be shared revenue so that each individual has the resources and “wealth” needed to live and live well. Public money—taxes—should protect everyone’s health and well-being; funding our schools, healthcare, emergency services, transportation, social nets, food assistance, veteran services, utilities, etc.; the social systems for the core population, so that individual freedom for equal opportunity is denied to no one. These resources should protect ordinary Americans in their unique cultures, traditions, and family values, as an investment in a healthier, more productive nation, in all its diversity.

Will Watkins: The concept that a society’s method of distributing resources is done in a way that benefits the individuals in that society in the most equitable manner. Protecting and ensuring basic human needs of food, clothing, shelter, health care, and access to capital are the fundamental core principles of society. In addition, the civil rights (relating to free speech, press, association, travel, and petition of government) of the individuals of that society and their ability to engage in democratic processes should have the fewest frictions as possible.

Robert McDermott: Socialism is where everyone gets education and healthcare while their dignity is protected into retirement and beyond. This happens because rich people pay a fair share of taxes and aren’t allowed to whine about it. Of course, it’s not perfect, the rich still get away with stuff but nothing like they do in your kleptocracy masquerading as a democracy, republic, whatever the f*ck fever dream you’re currently experiencing. I find it so tragically funny that my political views are considered moderate here in Ireland, but in your clusterf*ck of a country, I’d be a loony leftie radical communist.

K. Michael Groves: Employee owned workplace. Democracy in the workplace.

Dan P. Martin: Socialism is an inversion of capitalist risk/reward model where workers democratically elect their management and decide how to share the risks and profits, as well as use of the commons in production. To protect the commons, banking under socialism is controlled centrally to subsidize growth and development (or de-growth) to account for externalities beyond the scope of the workplace. The commons are inputs used in production other than human labor.

For example, centrally controlled banks would subsidize public transportation to promote its growth and development, recognizing the poor use of resources and unsustainable polluting effects of personal vehicles, which are disproportionately borne by those who benefit least.

SnailPowered: Socialism is acting in the interest of the good of a group, before personal gain. That is probably overly simplistic, but I think it truly encapsulates how it is used most often. Jimmy Carter may not have been a socialist, but I feel that it is undeniable that he practiced socialism as a leader. I found that during my time as a leader in the U.S. Army this definition of socialism is also what inspired men to follow me.

Chapter Two: The Importance of Being Bernie.

Just this small experiment illustrates the challenge in defining something as broad as socialism. In these extraordinary responses we can begin to understand the complexity of systems design. We heard political and economic themes, concepts like fairness + equity, class struggle, social constructs and corporate systems. Issues pertaining to basic rights; civil, human, natural rights and legal. Expressions of social constructs like dignity and morality. Centralized planning. Nationalization.

These are all aspects of socialism and the duality of defining it as an economic system and an ideology. And there’s crossover between the two, with ideological concepts informing economic structures and vice versa.

Before we dig into actual definitions and begin to dissect both the economic and ideological frameworks from a historical perspective, let’s first look at how socialism is addressed in our current society.

Perhaps the best way to do this is to peer through the lens of the mainstream media, which acts as both a reflection of our beliefs and a megaphone. While talking about socialism is no longer as taboo in this nation as it was during the Cold War era, it’s still difficult to find honest discourse outside of niche outlets. To demonstrate this, let’s check how socialism is spoken about on the establishment liberal mouthpiece, MSNBC.

This first snippet is from Lawrence O’Donnell, himself a prominent liberal media figure who has publicly stated he is a socialist, despite his establishment credentials:

“Socialism in the 1950s, in America, became a bad word. And we then became anti-intellectual about socialism. We as a country stopped thinking about what it actually is and just adopted, for the most part, a posture of fear against the word and the concept of socialism. And so, you know, when Medicare was proposed in the 1960s, the argument against it…well, it was essentially ‘it’s socialism.’ That was the entire argument. And it was kind of surprising that the argument didn’t work, especially because it was true. Medicare is socialism and everyone on Medicare in this country is the beneficiary of a very smart socialistic program called Medicare. And to deny that it’s socialism is to deny economic literacy. But that’s what our politics does.”

This is about as honest an assessment as you’ll hear from a mainstream figure on the proverbial left. But even though he’s a fixture on MSNBC, that quote is from a C-SPAN appearance. I have no doubt that aspects of socialist theory creep into O’Donnell’s signature op-eds on his program, but they’re certainly not readily accessible. This bit from Chuck Todd, on the other hand, is far more indicative of the manner in which socialism is addressed by even the supposedly most left leaning mainstream outlet.

“That got us thinking about other ISMs that could use redefining. If you like to commune with people, does that make you a communist? How about if you’re into fashion? Are you a fascist? If you’re left-handed, does that make you a leftist?”

Aside from the fact that Chuck Todd probably won’t be headlining comedy clubs anytime soon, this strikes at the heart of how socialism is generally dismissed, even among liberals. Also, he has a television program and I don’t. So there’s that.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have the constant din of anti-socialist rhetoric in the right wing media and political ecosystem.

Like Jesse Watters keeps working on his ghoulish Bill O’Reilly impressions, saying anyone who wants socialism wants to destroy America. Greg Gutfeld thinks that wanting socialism is like drinking after a hangover when you swore you’d never drink again. Jeanine Pirro freed the hook from her mouth long enough to quip that she thinks there’s a giant conspiracy of socialist forces ready to “do whatever is necessary to make socialism happen.” Fox News introduced a clip of former Home Depot CEO Bernie Marcus talking about socialism by “thoughtfully remarking “socialism sucks..”

Donald Trump told the United Nations that one of the world’s most serious challenges was socialism rather than the obvious answer that, in fact, he was. Ron DeSantis spoke out against communism, Leninism and socialism saying it denies the worth of the individual. And Ben Shapiro flatly stated, “capitalism is good because capitalism is freedom. Socialism is bad because socialism is tyranny.” Because, Ben.

Neither the casual nor devout consumer of mainstream news is ever really confronted with serious dialogue about ideology and political theory. So the information about socialism, as just one example, is either delivered in a bemused and dismissive tone on the left, or vituperative tone on the right.

It’s why Bernie’s presidential bids were seismic in terms of influence on our language and culture. Bernie’s steady drumbeat of messages about inequality, the 1%, universal healthcare, and student debt relief were vital. By pointing out the byproducts of a denigrated capitalist system he was able to open hearts and minds to evaluating other political and economic modalities without the need to expressly criticize capitalism or promote socialism.

In fact, I would argue that one of the reasons Bernie’s message resonated to the degree that it did is that he never expressly advocated for socialism. Even now, past his presidential candidacy years, he’s still cautious about the framing of his ideas. His new book, for example, is titled, It’s Ok to Be Angry about Capitalism, which might be the harshest criticism he’s offered. It’s not called “Capitalism Failed,” “Death to Capitalism,” “Down with Capitalism.” Just, it’s okay to be angry.

But he’s particularly good about calling out the people who take advantage of the system. The uber wealthy. The oligarchs. The 1%. Millionaires and billionaires. And when he takes capitalism to task, it’s usually couched in language that blames the wealthy for corrupting the system, not the system itself.

Even his framing as a democratic socialist was a high wire act. One that is actually false. As Unf*cker Dan Garcia pointed out, in the United States we have the concept of social democracy and democratic socialism backwards.

Social democracy, sometimes referred to as “market socialism” seeks to construct socialist systems on top of a market based system that preserves private property, markets to determine price and production, wage labor and shareholder capital. Democratic socialism, or “classical socialism” on the other hand, takes a more Marxian approach to organizing economic systems such as labor-owned production and centralized planning.

It’s not that Bernie was being disingenuous, and I’m not sure how much semantics matter to even the most curious member of the public. I just think that it was far easier to build a national platform around the term democratic socialism, and once it started it was too late to shift gears. But since we’re placing so much emphasis on the importance of language, it’s worth making the distinction here.

Either way, what Bernie accomplished is not to be understated. Over the past dozen years or so he has helped mainstream ideas that were the third rail in the U.S. Not even for discussion in polite company. Stuff that was spoken about on college campuses, and barely so. Maybe incorporated into white papers at left-leaning nonprofits and think tanks. That’s why I think he took such a measured linguistic approach, always refraining from stating that capitalism is a failed system. Stopping short of calling for a socialist revolution. Using terms like uber-capitalism, socialism for the rich, democratic socialism, social safety nets, Scandinavian models, corrupt oligarchy, corporatism, etc.

But now that these ideas have once again been released into the wild, and younger generations are especially willing to examine the merit of systems other than capitalism, we’ve reached an interesting point in capitalist history. Most thinking people understand that what we have now, no matter what you want to call it—capitalism, corporatism, oligarchy, inverted totalitarianism, whatever—it’s not working. Inequality is widening. Entire systems keep failing. The pandemic exposed the fragile nature of globalism.

And oh, by the way, we’re cooking the planet.

Strictly speaking of the United States—and this isn’t being ethnocentric, just pragmatic as we remain the key driver of the global economy—the immediate future looks bleak in terms of leadership; with Joe Biden seeking a second term and what is shaping up to be the most evil cast of characters ever assembled running against him. And I get that it’s frustrating and a lot of shit can happen in just a few years, but I truly believe that the 2008 financial crisis, the Occupy movement in 2011, and rise of Bernie Sanders potentially ushered us into a new era brimming with opportunity to evaluate the history of economic and social systems in order to design new ones.

But, as we’ve said before, how can you know where you’re going if you don’t know from whence you came? And before we can even get there, we have to know what the hell we’re talking about.

Chapter Three: A brief overview of crucial concepts.

As we saw with the confusion surrounding social democracy vs. democratic socialism, it’s important to nail down a few key concepts and terms as we move through this discussion. As we’ll cover in upcoming chapters, the language and concepts surrounding socialism have evolved over time. The most enduring contributions to our general understanding, however, come from Karl Marx. Much of what we’ll pull from is largely attributed to his work in Das Kapital, The Communist Manifesto and various other works completed by Friedrich Engels after Marx’s death.

Importantly, the roots of socialism predate Marx. But one of his great contributions was to define certain ideas and build them into an economic framework. At the time Marx was writing, he viewed the classes in the capitalist system generally as the working class, or proletariat, and the bourgeoisie. The workers and laborers comprised the proletariat and the owners of capital, sometimes referred to by Marx as the guardians, were the bourgeoisie. Later on, the rise of the service and merchant class—those who stand to profit from trade but still lack the status of a capital guardian—would develop into the petit bourgeoisie.

While it may seem elementary to us today, one of his innovations was in valuing capital. In the simplest of terms, prior to this period commodities were viewed in terms of their use value. What the raw form of a material is worth. The exchange value is its value in a transaction.

Prior to Marx defining value in such terms, most models strictly considered use value and attempted to equate quantifiable values between commodities. X amount of corn is worth Y amount of iron, as he proposes in Das Kapital. But the process of turning a material into something with an exchange value, or worth in a marketplace, involves a degree of labor to transform it from its natural state. As he wrote:

“The value of a commodity, therefore, varies directly as the quantity, and inversely as the productiveness, of the labor incorporated into it.”

So again, sounds super simple but it’s hugely important to understanding the roots of what will ultimately be his critique of the entire capitalist system. By valuing the inputs of labor and crediting this ingredient as that which gives exchange value to a commodity, he makes labor the central economic ingredient in the value of production. Or as Marx calls it, “incorporating living labor with their dead substance.”

When we talk about the means of production, another central element to economic theory, we’re talking about everything involved in bringing a product to market. Tools to extract raw materials and the transport of materials and goods. The equipment used to add value to a raw material. Essentially everything outside of the raw material and the labor required to convert it into something worthy of an exchange value.

Another one of the keys to differentiating between capitalism and various forms of socialism is an understanding of private property. Essentially, who owns the means of production. Who owns the tools, the factories, the machines, the transportation, etc.

In a capitalist society, it’s pretty straightforward. The guardian class owns the means of production and therefore determines how it’s used. In a socialist society, the workers themselves would theoretically own the means of production thereby stripping the guardian class of such private property. This is one key distinction we can make, for example, between modern social democracy and democratic socialism. The former would still allow for the existence of private property, but utilize state programs of taxation to redistribute the surplus capital derived from production. The latter would flow directly to the working class.

Now, all of this paints a small picture within a much larger system. If we jump ahead in our timeline to when the Bolsheviks took control of Russia and attempted to convert from a feudal economy to a collective, the concept was theoretically based upon a more democratic socialist style economy. A “soviet” is essentially a local, democratically elected council that would determine the governance and economic activities of a defined region. Again, in theory this democratic process would give ownership and authority to control the economy and grant quasi-ownership of the means of production. The vision of a union of soviets controlling pieces of a large system was the genesis of the Soviet Union. Later on we’ll discuss how this concept never came to fruition, but just the idea of it is an approximation historians have to how the working class could own the political and economic process within a larger system.

Building on this, the natural question arises of how exactly labor owned and controlled operations would participate in the larger economy and thrive under a political system. That’s where the theories diverge even more. Again, as we move through the series we’ll give examples of different interpretations and systems that evolved from attempting to answer questions like this. But for now, we’re still in the definitions and level-setting phase so let’s continue with a few questions because we can already see how complications would arise along the way to building out a socialist infrastructure, not only within a defined territory but in terms of how this economic system would fit into a global marketplace.

Here are just a questions that illustrate the complexity of these theories:

- If market forces such as supply and demand aren’t solely responsible for determining price, then how are goods and services valued?

- How do you determine output?

- We’re used to the idea that the price of something is what the market will bear or people are willing to pay for it. Under a socialist system, who values the inputs such as labor and raw materials?

- If ownership of property and the means of production are distributed among the working class, how do we determine the value of a share? Is skilled labor worth the same as unskilled labor?

- Where does capital investment come from if not the markets and the bourgeoisie?

- If surplus value—the amount above the value of labor and material inputs—is split among the working class, then how are deficits accounted for?

- We’re conditioned to believe that innovation is fostered by the desire for capital accumulation. Under a socialist system, what are the key incentives to innovate if all surplus wealth is distributed evenly?

- We’re also conditioned to believe that scarcity increases value and abundance detracts from it. If scarcity is a market force then does it still exist in the absence of a free market? Does it even matter?

Attempts to answer these and many other questions naturally involve government intervention to a large degree. Some believe that many of these questions are answered with a centralized planning model whereby outputs are predetermined by central authorities that set fixed production amounts. Modern day China is a good example of this. The Soviet Union was a bad example. What’s the difference?

In the years following the Cuban Revolution, centralized planning looked to be paying dividends. Then came the lean years, or the “special period” as the Cubans called it, when centralized planning failed and their primary market collapsed with the fall of the Soviet Union.

Some believe that you can have decentralized planning in terms of output and control over the means of production, but it’s difficult to pinpoint enduring examples of success.

Now, students of economic and social theory will recognize our discussion thus far as pretty basic. But, again, it’s important to establish a common vocabulary and to frame inquiries in a way that contextualizes the challenges different theories present in the real world. From here we can build on the key concepts and terms such as labor, surplus, means of production, centralized planning, scarcity and so on to see how socialist theory was interpreted at different times throughout its history.

For the real aficionados, I promise that this will get deeper as we go. As preview, we’ll cover notable figures such as Cesare Beccaria, Jeremy Bentham, Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, Mikhail Bakunin, John Stuart Mill, John Dewey, Rosa Luxemburg, Peter Kropotkin, Karl Kautsky, Emma Goldman through to Michael Harrington and even Bernie.

We’ll introduce many of these characters in the next essay when we examine distinct epochs of socialist history beginning with the real socialist roots that predate Marx. So with the key concepts and terms under our belt, we’ll build our timeline and bring central players into the mix on our way to distinguishing between Socialism, Marxism, communism, anarchism, utopian socialism, Maoism, Leninism, Stalinism, democratic socialism and more. We’ll add color to this discussion by evaluating historical examples in Cuba, China, Scandinavia, Russia, Africa and Latin America.

Then we’ll focus specifically on the United States as a microcosm of all of these approaches. Concepts, movements, key figures, timeline and an evaluation of where things stand today.

Thanks for jumping into the river with me. Hopefully when we emerge, we will indeed be different as no doubt the river will be.

Here endeth Part One of Understanding Socialism.

Image Description: Text that says Socialism over a globe

Image Description: Text that says Socialism over a globe

Part Two: The Seeds of Socialism

Summary: Believe it or not, we’re still not up to Karl Marx, because we’re mired in the turn of the 19th century. Part Two reveals the progenitors of socialist theory toward the end of the Enlightenment era. Charles Fourier, Henri de Saint-Simon and Robert Owen lay the groundwork coming out of the American and French revolutions by imagining new societies and mechanisms of power. In their writings, we begin to see the roots of Marxian philosophy and draw upon concepts and experiments that would influence Marx and others during the second industrial revolution.

In Part One of Understanding Socialism, we noted that G.W.F. Hegel’s work had a profound impact on a young Karl Marx. Hegelian dialectic, the study of thought and reason by synthesizing contradictions into a higher truth, is the beating heart of Marx’s critique of capitalism. The conflicts that Marx sought to resolve were material, as opposed to the abstract that Hegel sought to reconcile. In this material setting, Marx studied the contradictory nature of the interests between labor and the capitalist class. He believed them to be so extreme as to be inevitable, and that numbers, strength and political will favored the working class. The rift would worsen over time, lead to a global popular uprising and eventually to what he called the withering away of the state.

This ultimate expression, the formation of a utopian socialist society, informs our vague notion of communism. A moneyless and classless society. Interestingly, when attempting to draw upon non-material influences, his intellectual predecessor Hegel arrived at a different conclusion, one that favored monarchical rule.

Both were wrong.

Monarchies died at the hand of nationalism. The working class never united across national boundaries. The state has only gained power, far from withering away.

Why, then, do we give so much credence to the philosophies and prognostications of these thinkers? How can there be so many competing visions of socialism? Is socialism a moral and ethical discipline, or is it political and economic? We add these to the ever deepening layers of questions surfaced in Part One that were more practical in nature. Questions regarding the value of labor, what drives a market, foundations and formations of capital, property rights and ownership.

So what’s the throughline in all of this?

In our capitalism essay, we demonstrated how our views of capitalism, the very definition of it, in fact, has changed over time. New thinkers. New nations. Technology. Innovation. Changing cultures and attitudes. All contributing to the evolution of thought. The river Heraclitus spoke of.

And, whether it’s Adam Smith and capitalism, Karl Marx and socialism, Kant’s transcendental idealism, Mill’s utilitarianism, Dewey’s pragmatism or Goldman’s anarchism, there is one constant. Every system and the intellectual behind it strives to organize society in a framework that incorporates the practical aspects of human nature and provides a positive outcome for the greatest number of people.

The great philosophers are engaged in conversation. Their ideas echo over generations and weave their way into new modalities. We speak of Hegel because his process and way of thinking informed Marx. Karl Marx was offering a critique of an economic system formulated by Adam Smith and François Quesnay. Socialism was conceived 50 years before Marx even put pen to paper. So, to understand the evolution of socialism, we have to contextualize the various epochs through which it evolved. Understand the motives of those who drove each iteration. Dig into the external factors that altered the nature of it. Wars. Famines. Movements. Attitudes.

So, we have to do more than just offer definitions and examples. We have to weave a larger narrative that contemplates all of these factors and sets them in historical context. So, let’s start at the beginning.

Chapter Four: A Better Way?

The Enlightenment, known as the long century in Europe, opened the human mind to the possibility of moving beyond the feudal structures that dominated society throughout history. Declared the “Age of Reason,” intellectuals began investigating life through an epistemological lens. Reason and science over faith. A Cartesian approach to philosophy that placed the human mind and experience at the center of exploration rather than God. Prior to the Enlightenment, feudal structures dominated the landscape of empires and burgeoning nation-states, most of which remained tied to monarchies, religious control or a combination thereof.

But in the 17th Century, and throughout the 18th, a newly formed intellectual class was beginning to think differently about how to organize society. A new economic structure based upon markets gave rise to the theory of capitalism. Advances in agriculture allowed for populations to grow after being decimated by famines and plagues in centuries prior. A middle class was emerging, with artisans and merchants occupying new roles in society.

And there was a New World, across the ocean from where this intellectual revolution was occurring, that held the promise of secular and democratic rule. And this is where our story begins. At the dawn of the 19th Century. In the new experiment, it was the time of Jefferson, Madison and Monroe—iIntellectual products of the Enlightenment, political products of an anti-monarchy revolution. Forged in blood, to be sure. But brimming with possibilities.

And, as the New World matured and broke free of the shackles of the European patriarchy, so too were the citizens of Europe agitating for something new. For them, it was the time of Napoleon, King George III, the emperors Alexander and Nicholas in Russia. The patchwork of Germanic states were still organized in feudal territories, each owing allegiance to blood rulers and aristocratic systems. This was prior to the epic orchestration and consolidation of Germanic states under Otto von Bismarck, which would come later in the century.

But, it’s in these territories that a new breed of philosopher would build upon Enlightenment principles and begin to fuse them together with possibilities that abounded, as markets connected humanity at a pace never before witnessed in human history. It was the height of G.W.F Hegel, the German philosopher who inspired Marx’s material dialectic. But it was in France where the true roots of socialist theory emerged. And it was a businessman from Wales who made one of the first practical attempts to implement it.

Bentham and Beccaria’s Building Blocks

(How’s that for alliteration?)

Again, timing matters. We’re speaking loosely about the early 1800s. Critically, just prior to this period, there were two revolutionary moments that reverberated the world over. The American Revolution, first, and the French Revolution a decade or so later. I bring this up because there are those who believe that early socialist roots can be found in the Jacobin movement and brief ruling tenure during the French revolution. While there are traces of socialist theory, the Jacobins were a political force, first and foremost. So, while there’s crossover in some of the desired outcomes such as secular rule, equal rights and universal education, the Jacobins favored strong central authority and were notably light on economic policy. I mention it because the French Revolution is sometimes tied to the birth of modern socialism, but I see it more as a cousin than a parent.

One of the difficulties of distilling any sweeping construct such as socialism into even a multi-part series, is in determining which of the vast number of theorists to include. In each, we find remnants of prior intellectuals and eras, some small innovations and some profound ones that fill out the mosaic of thought. Most texts consider three men, that we’ll cover in a moment, as setting the roots of what we would consider socialism. But, since everyone is building on ideas that came before them, there are two figures in particular that should be in the conversation: Milanese aristocrat Cesare Beccaria and British intellectual Jeremy Bentham.

We’ve spoken of both men before. Beccaria is most known for his book On Crimes and Punishments, which proffered the idea that criminal justice should be preventative rather than punitive, and suggested myriad reforms that remain hallmarks of jurisprudence to this day. But, like many other great intellectuals throughout history, Beccaria was also a noted economist and social theorist. He was the first to write that the quantity of a good had an inverse relationship to its price. In other words, the theory of supply and demand. He also wrote extensively about tariffs and trade and their effect on behavior. In just these examples, Beccaria had a massive impact on economics and the law. Regarding the latter, luminaries from Voltaire to Thomas Jefferson lauded Beccaria’s work.

Importantly, Beccaria wrote early enough to influence Bentham, who was far more productive and lived a good deal longer than Beccaria. Bentham not only wrote on criminal justice, he contributed vital work on taxes, welfare reform, separation of church and state, trade, policing, democracy and more. He was an infinite well of inspired thought that challenged establishment thinking throughout Eastern and Western Europe. He closely observed uprisings in Russia and the French Revolution, and was considered to be one of the most important public figures of his time. Today, he is best known as the founder of utilitarianism, in fact coining the term.

Utilitarianism is essentially a moral theory that can be applied in the political, economic and carceral realms, and it basically holds that any action that demonstrates a positive social good is just. An early example of greater good theory, basically.

So, why these two? Out of scores, if not hundreds, of truly remarkable Enlightenment thinkers, are Beccaria and Bentham so relevant? Especially since they were most productive at the latter stages of what historians consider to be the Enlightenment.

Well, I think that’s part of it. Beccaria and Bentham were most productive at the moment the western world was transitioning from the Enlightenment to the Modern Era. So, in many ways, they were the products of all the great thinkers who came before and the ones who were handing the baton to the next generation. Remember that monarchies and organized religion were still clinging to administrative power and lording over quasi-feudal economic structures. All of this was crumbling during the industrial revolution and the political upheavals in Europe and across the pond.

So, here we have two radical intellectuals promoting democratic thinking in every realm, from policing and incarceration to representative government and welfare. They were beginning to think in systems, seeing the relationship between economic conditions and behavior; to view economic justice as a responsibility of the state through sponsored welfare, guaranteed employment, fair labor and trade practices.

They understood the interconnectedness of social, economic, political and legal disciplines and how they related to the construction of moral and democratic societies. All of this dramatic historical stuff was just feeding into them. The founding of America, the crumbling of monarchies, growth of industry, surging inequality alongside the creation of a middle class, wars, famines, abundance, revolutions, secularism.

Essentially, it was a dizzying time. All of the structures that had guided empires for centuries were disintegrating at once. Market economies opened the world to new economic possibilities. Democratic rule was challenging authoritarian monarchies. New classes were emerging. So figures like Beccaria and Bentham were grappling with these implications, imagining new social, political, legal and economic constructs that could manage the change and attempting to reorganize society in ways not contemplated since the time of Aristotle.

So, as the world entered the 19th century, a new breakthrough was imminent.

Chapter Five: Socialism Takes Root From The Seeds Of Revolution.

The second industrial revolution and the Revolution in France set the stage for the birth of socialist theory. In everything we discussed so far, particularly at the turn of the 19th century, we see how intellectuals like Beccaria and Bentham were assimilating these revolutionary inputs into moral and ethical frameworks that informed new theories in economics, politics and the law. And together, these theories informed new constructs for society writ large.

But, at the core, there were two main constants. The state and class hierarchy. In many ways, the next big breakthrough was to take these new frameworks to the next logical step. And, in this, we see the roots of socialist theory. One that challenges the last two vestiges of Enlightenment thought and drives us into the modern era. The idea that all of these advances might themselves supplant the traditional role of the state and thus lead to a new paradigm, if not elimination, of class hierarchies altogether.

That’s the fundamental shift introduced by Henri de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier of France and Robert Owen from Wales, considered by most to be the true intellectual progenitors of socialist theory.

To introduce us to this trio, I want to bring in the work of Michael Harrington. Harrington was the founder of the Democratic Socialists of America, who was a major left wing figure in the United States, author of eighteen books—including the one we’ll pull from, titled Socialism: Past and Future, his final one.

“Fourier and Saint-Simon had unhappy personal experiences with the upheaval in France. They wrote as the industrial revolution was taking off. Owen was a factory owner, and Saint-Simon might be said to have been the first philosopher of industrialism and, for that matter, the first “historical materialist,” with his emphasis on the underlying importance of the economic in social and political history. Both of them greeted the new technological world as a means to their utopian ends. Fourier is the exception, the one of the three who was not that enthusiastic about industrial progress. Yet he was far ahead of his time as a thinker who made an almost Freudian definition of what socialism would be.”

Harrington is making an important distinction between the Jacobins, Enlightenment thinkers in the vein of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and economic theorists such as Quesnay and Smith. They were the first to view industrialization, markets and economic mobility between the classes in a societal construct that might inevitably, with the right inputs and under the right circumstances, evolve into an egalitarian society that rid the world of centralized rule and class distinctions. In fact, it was Saint-Simon who first proposed the idea of “withering away of the state.”

As Harrington also notes, however, Fourier had his suspicions about the burgeoning merchant class, something that would echo in Marx’s critique a few decades later. Here he is in his own words:

“Are merchants alone exempt from the social obligations imposed on all the other classes of society? When a general, a judge or a doctor is given a free hand, he is not authorised to betray the army, despoil the innocent or assassinate his patient. Such people are punished when they betray their trust; the perfidious general is beheaded; the judge must answer to the Minister of justice. The merchants alone are inviolable and sure of impunity! Political economy wishes no one to have the right of controlling their machinations. If they starve a whole region, if they disturb its industry with their speculation, hoarding and bankruptcies, everything is justified by the simple title of merchant.”

Right away, we can see some of the seeds of thought that would germinate in Marx’s works. Mistrust of the merchant class. An organic movement toward a stateless society. We’ll get to Owen in a moment, because, as I mentioned earlier, he was the first to put these theories into practice. But I want to make another distinction between these early theorists and where Marx would eventually land. Saint-Simon, the more optimistic of the two Frenchmen, was critical of the bourgeoisie but supportive of industrialists and financiers, the ones who leveraged the means of production and made things. As Harrington posits, “how can one man inspire both the banking industry and the socialist movement?”

He continues to suggest that it was Saint-Simon’s followers who “squared the circle,” by saying,

“If government was now to be replaced by society as defined functionally, then the critical question: What is society and who are its functional leaders? For Saint-Simon, the answer was industrialists and bankers…in contrast to the coupon-clipping bourgeoisie.”

Again, we’re at the beginning stages of socialist theory, when old structures were beginning to break down and new leaders were inspired by secular potential rather than pre-Enlightenment deterministic thinking. Every idea was groundbreaking and held potential. But we can also see that even these early thinkers faced the same queries we raised in Part One regarding ownership of production, generation of capital and investments, role of governance and so on.

As we continue to traverse the landscape of socialism, we’ll periodically allude to adjacent but no less important movements that either inspired socialism or were inspired by it. Just know that passing references to such important milestones and movements is not intended to diminish it, just to help us stay focused on the task at hand. Among the tributaries such as utopianism, utilitarianism and anarchism, it’s important to recognize that feminism was a dominant corollary of most authentic socialist movements. This is particularly true in the case of our three progenitors. As Fourier proclaimed, “The degree of feminine emancipation is the natural measure of general emancipation.”

Even more than Fourier, the Saint-Simon movement came to embody the whole of the new socialist movement as encapsulated in the words of George Lichtheim, who wrote:

“Socialism was a faith—that was the great discovery the Saint-Simonians had made! It was the “new Christianity,” and it would emancipate those whom the old religion had left in chains—above all woman and the proletariat!”

But, if Saint-Simon and Fourier represent the intellectual foundation of socialist theory, willing to challenge feudal society structures, nobility and norms, then it was the Welshman Robert Owen who gave rise to socialism in practice.

Paradise Lost: Robert Owen and New Harmony

Robert Owen was an exemplary member of the newly defined merchant class, rising through society as a successful businessman. His experience as a benevolent employer led him to, as Harrington notes, “try to convince the British and American elite that social justice was a pragmatic investment. During the very hard times after the Napoleonic Wars, there was widespread misery, unemployment, and, as a result, fear of revolution. The cost of caring for the poor—outlays that had been taken at considerable measure as an insurance policy against a French-style revolution in Britain—rose even as the wartime prosperity ended.”

Owen had a weakness, as perceived by the ruling class, however, and that was his atheism. This shut him out of much of upper echelon society and contributed to his own radical transformation from good natured elitist to working class champion. Owen took his fortune to the United States to establish New Harmony, one of the earliest models of utopian socialism we can point to. Don’t get me wrong, there were multiple attempts throughout Europe and even some in the United States, but what Owen was able to construct due to his significant personal means stands as one of the ultimate tests of faith in socialist doctrine.

In 1825, Owen set roots in Harmony, Indiana, a village that was home to a small Christian group. Setting himself up as the guardian of the community, Owen guided a handful of followers through the establishment of a new constitution and a number of communal governing councils designed to put economic, political and labor decisions into the hands of the members.

The experiment failed within three years, and Owen was forced to give up the community, at which point he returned to Europe. But, in these three years, enough historical information and context was gathered, as though in a human laboratory, to dissect the benefits and downsides of a community organized in such a fashion. As the Socialist Alternative organization notes:

“By turning the community into a voluntary association, a very different sort of social arrangement came about. Those who came over to New Harmony were a mass of pauperized laborers, deprived of work in the midst of an agricultural recession. Many forced into criminality, these layers had none of the social commitment that Owen had expected, but instead sought unemployment relief, turning the community less into the utopian paradise Owen foresaw and something more akin to a soup kitchen.”

I want to go way into the future for a moment to highlight something we covered in our series on the presidency of Bill Clinton. Recall that one of the features of the so-called New Democrat playbook was the attempt to turn every struggling laborer into an entrepreneur. The experiment was an abject failure. And, it continues to be, as demonstrated by the ongoing effort of organizations like the Clinton Foundation, who continue to believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that everyone wants to own a business. The vast majority of working people are looking for steady, gainful and, if possible, rewarding employment, not the risk and upheaval associated with entrepreneurship. It was a lesson that Robert Owen learned the hard way in the 1820s.

Moreover, Owen’s attempts to inculcate the community with his personal views on atheism only turned many of the community against him. So, the whole thing fell apart in rather short order, despite the communal environment, freedom of movement and expression and financial security blanket from Owen.

I wanted to end on this example. And, the next section will include a similar one just a half century later to demonstrate a few key points. First off, Marx was a student of all of this activity that inspired his work, one way or another. The New Harmony experiment, among others before and during his time, would inform his view of utopian socialism. Some might be surprised to learn that the man so closely associated with this vision actually took a rather dim view of the attempts to organize communal spaces and utopian societies. This is where we see the rational and scientific, if not anthropological, intellect of Marx.

Marx understood something more about human nature than those who had come before him, and was able to synthesize this understanding into his approach. Harrington puts it perfectly:

“Marx, the student of Hegel, knew perfectly well that the means are themselves the end in the process of becoming. By changing the definition of how one gets to socialism, you change the definition of socialism itself.”

What Owen and other revolutionaries failed to understand about the nature of revolutionary change is the groundswell. The process. The catalyzing events required to inspire the masses and move them to change their own circumstances. It’s why Marx is so important today, even if he misread the outcome and perhaps the speed and totality of capitalism’s momentum and agility; its ability to transform over the decades to do just enough to keep the masses in check and prevent uprisings.

Marx knew that societal transformation couldn’t, and wouldn’t, be thrust upon even those who stood to benefit the most from it. It needed to be bottom up, not the other way around.

So, that’s where we’ll pick up next. The groundwork has been laid, the foundation set. In the next essay, we enter the heart of socialism to examine the life and impact of one of the most important people in human history.

Here endeth Part Two.

Image Description: Portraits of Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill in a gallery.

Image Description: Portraits of Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill in a gallery.

Part Three: The “Critique Phase,” 1825–1870.

Summary: We have the third installment in our socialism series, where we resume our journey beginning in 1825 and the collapse of Robert Owen’s New Harmony experiment. This next chapter introduces the work of John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx and touches on Mikhail Bakunin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, both of whom we’ll explore more fully in Part Four. Not gonna lie, this series may never end. But this is a critical piece of the puzzle that we’re calling the “Critique Period,” lasting from 1825 to around 1870. This era is punctuated by widespread revolts in 1848 that inform some of the new thinking around capitalism and the plight of the working class — all leading into the explosion of socialist philosophy that hits the mainstream consciousness following the events of 1870 (again, for Part Four).

In Part One of our series, we set the table for a lengthy discussion about one of the most amorphous political, economic and social concepts in history. To illustrate this, we began with the words of our audience, whom we asked to describe socialism as succinctly as possible. The answers were as diverse as they were thoughtful, and it truly set the tone for the series. We offered some of the more dubious modern claims about socialist theory from mainstream mouthpieces, talked about the importance of Bernie Sanders in normalizing concepts associated with modern socialism in the United States, and introduced some of the key concepts and vocabulary most commonly used in socialist economy theory.

Then, in Part Two, we went back to the origins of socialist theory by looking at the bridge between the Enlightenment period and the modern era with philosophers such as Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, who in turn laid the groundwork for what would become socialist theory. This is where we introduced three men considered by some to be the progenitors of socialism: Saint-Simon, Fourier and Owen.

My biggest takeaway from revisiting this period in history is just how profound their ideas were in a period when humanity was emerging from the feudal structures that dominated European culture for centuries. And, I should point out that most of our discussions center around the European experience with socialism, though we will cover other expressions of parallel thinking in other cultures and periods throughout history. But the concepts that we wrestle with today are most often associated with European philosophers and the influence they had on the world, so that’s what we’ve concerned ourselves with for the most part.

So, if Part Two described the foundational period, we’re heading into what I’m calling the “critique period” of socialism. The critique period is a relatively short period of time, but it is perhaps the most essential period to understand. The relevant philosophical period associated with Saint-Simon, Fourier and Owen is the first part of the 19th Century; but, as we’ll see, there is a good deal of overlap between their productive years and what we’re about to cover.

I’ve chosen to bookend the foundational period and the critique period with two important events that relate to manifestations of socialist theory—Robert Owen’s New Harmony experiment in 1825 and the Paris Commune in 1871. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of these years and the enduring influence of the philosophers most associated with this period, each of whom builds upon the concepts of our founding trio and, in some cases, collaborates with them. In terms of the nomenclature, please know that these aren’t formal periods or names that you’ll find associated in any texts. It’s a shorthand for how I’ve personally come to understand the evolution of socialism. I call it the critique period for a couple of reasons.

First off, is that the philosophers we’re going to cover are primarily offering a critique of capitalism and striving toward the development of a general system theory that can be applied in political, social and economic realms. During this time, we witness both great collaboration and disagreement among leading philosophers striving to create these systems and wind up exiting this period with several expressions; mostly notably utilitarianism, socialism and anarchism. There’s a ton of overlap between them, and each will ultimately spawn scores of new doctrinal tributaries.

The other reason to consider this more of a critique period is that these theories are in development. They’re responding to both the foundational theories and unfolding realities of a maturing capitalist society. But they haven’t yet reached the application phase, or what we’ll call the “praxis” phase, to borrow from Marx. That’s what we’ll cover next, from the Paris Commune through the Russian Revolution.

So, we’re going to actually end this episode right before the Paris Commune of 1871 because, in so many ways the inflection point in European history and socialism as a burgeoning doctrine is the year 1870, one of the most pivotal years in modern history. For the American UNFTR audience, imagine what 1945 is to American imperialism, 1968 is to the civil rights movement or 2001 is to civil liberties all crammed together in a single momentous year. Truly fascinating stuff.

In terms of the protagonists, as expansive as this era is, I’m going to limit our discussion to four main philosophers. A few words on this approach before we begin Part Three in earnest.

We’re going to cover the works of John Stuart Mill and (finally) Karl Marx. These two giants will kick off the critique period; and two other massively influential theorists, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Mikhail Bakunin, will kick off Part Four and serve as our bridge from the critique to praxis.

Students of Marxism, socialism, anarchism or history in general might find my omissions a bit startling. It would be impossible to fully explore the voluminous literature and philosophers whose work contributed so much to the conversation. So, I narrowed it down to these four for reasons that will hopefully make sense as we move forward. But Part Four will also introduce us to a slew of other big names.

Briefly, I believe that, in totality, Mill, Marx, Proudhon and Bakunin represent the most significant and enduring contributions to our understanding of socialism and challenged establishment thinking in a way that altered the course of history. And, in many ways, where they diverged wound up being more important and instructive than where they were aligned. Because, after this period, socialist theory would splinter into multiple disciplines, much like the major religions of the world did throughout history.

And, in the truest actualization of dialectical materialism, this brief period is a study of both the material influences of philosophers upon the world and the world upon them. In this exchange, these four challenged the foundations of modern society, culture, government, religion and morality in such a manner that we feel the resonance of their words to this very day.

Chapter Six: Revolutionary Conditions.

In the beginning of the 19th Century, the European continent was convulsing with new political, spiritual and social energy. The trio of Saint-Simon, Fourier and Owen set the world’s collective imagination on fire, and new theorists were poised to build on their proposals for how to organize a new world.

Since we’re choosing 1825 and the collapse of Owen’s American New Harmony experiment as our jumping off point, it’s important to get a feel for the times. So, before we unpack the theories of our main characters today, let’s talk about the circumstances in which they were writing as intellectual heirs to the founders of socialist thought.

As I mentioned, there is a good deal of overlap between our theorists, and in many cases they were friends, enemies and even collaborators. For context, Beccaria and Bentham were born in 1738 and 1748, respectively. Saint-Simon, Hegel, Owen and Fourier were born about a half a generation later, just enough time to soak in the lessons of these founders and read their work in real-time in their formative years. The philosophers in the critique period were all born after the turn of the century and were most active from New Harmony through to our 1870 ending point, with the exception of Proudhon, who died in 1865 but was incredibly influential until that point, and perhaps even more so thereafter.

What Mill, Proudhon, Bakunin and Marx were experiencing during these years is so important because European life was advancing at a revolutionary pace unmatched in recorded history. For one, the population of Europe doubled in the 19th Century, from 200 million to 400 million, thanks to advances in industrial agriculture and the widespread use of coal, among other factors. These inventions facilitated industrialization on a colossal scale and contributed to the seismic changes in class structures, the nature of labor, urbanization, transportation and the development of international trade. It should be noted that this growth in population occurred in spite of historic European migration to America and other destinations.

Of course, not all of Europe developed in lockstep. There were surges and depressions, shifting power dynamics, wars, famines—all the normal events that punctuate the course of history. So, as a practical matter, I’m going to talk in generalizations. But, to be clear, political, industrial and social developments varied dramatically from England to Italy, Russia to France, and so on. But, on the whole, what our theorists were observing was nonetheless extraordinary, and they were able to connect several dots when committing their observations to the page.

In order to stay focused, I’m not going to cover major geopolitical or religious changes, though they certainly contribute to the evolving social landscape. For our purposes, there are a handful of critical innovations that ultimately impact the social and economic elements of socialism because they facilitated growth that would ultimately challenge the traditional political and religious structures that dominated European culture for centuries prior.

Perhaps the most significant ingredient in large scale economic growth, beyond technological innovations, was something we largely take for granted. Private property and its associated legal protections. English common law and the Napoleonic Codes would set the template for most of the developed world in terms of property rights and help usher in a slew of economic innovations in banking as a result.

Property could be pledged. From this tangible asset, one could build through leverage; and so long as the newly formed codes protected this underlying asset, one could also then take risks and take advantage of yet another innovation: the shareholder.

Private property pledged to a banking institution opened the burgeoning petit and haute bourgeoisie to the capital markets and allowed them to create corporate structures that could also invite capital from outside shareholders. If you’ve ever wondered what the Marxist obsession with the concept of private property is all about, this is it. Serfs and peasants didn’t possess land or assets and were therefore left behind in the industrial fervor. But, from the peasant class, there emerged a new class of laborer, consigned to working in urban factories and trading one form of serfdom for another.

This is the economic liberalism that Adam Smith envisaged. The innovations that Jeremy Bentham was reacting to. The very real circumstances that moved from the theoretical to the tangible. And it was the very real effects of economic liberalism that Marx, Mill, Proudhon and Bakunin saw unfolding in front of their eyes, often to their horror.

“It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood, it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled. It had a black canal and a river that ran purple with ill-smelling dye, and vast piles of building full of windows where there was a rattling and a trembling all day long, and where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness. It contained several large streets all very like one another, and many small streets still more like one another, inhabited by people equally like one another, who all went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavements, to do the same work, and to whom every day was the same as yesterday and to-morrow, and every year the counterpart of the last and the next.”

This passage is from Charles Dickens’ introduction to Hard Times in 1859. Few described the soot and grime as vividly as Dickens. The cultural impact of such descriptions were as profound in Europe as Jacob Riis’ tenement photographs or Upton Sinclair’s fiction in America at the turn of the 20th century. Against this backdrop, our theorists chronicled the emergence of the new working class, subjected to horrific conditions in factories and urban hellscapes and experiencing the underbelly of capitalism. The new form of serfdom was called wage slavery. Hundreds of thousands of able bodied working men moved from the fields to factories within a generation, and as the capitalists thrived, they searched for ways to increase profits and productivity, leading to yet another devastating development that sent children and women into the factories, sometimes alongside the men and sometimes in place of them.

The economic dislocation of the newly formed labor class was horrifying. But, in this, our philosophers saw potential. The potential to form a new center of political and economic power in the hands of the working class. Without the laborer, the factories could not run. And the new working class was more literate than the peasant laborers just a generation or two before them.

The working class was a tinderbox, ready to explode at any moment because the industrial economy differed from the sleepy agrarian economy. It was subject to boom and bust cycles, shocks that often occurred with devastating frequency over a matter of a few short years.

In short, the risks and stakes were so much higher for the new working class than even the peasant class that had come before. This modern economic dislocation was wholly unnatural, brought about by the artificial forces of capitalism, as opposed to the natural occurrences that plagued feudal economies of the past. Sure, droughts, famines and diseases had devastating effects on feudal economic systems, but everyone experienced them. They were indiscriminate. On the contrary, in the early stages of capitalist industrialization, the bourgeoisie was far more insulated from periodic shocks due to the nature of capital markets, assets and private property protections. For this, let’s bring in one of our protagonists to explain the risk differential between the new laborers and the capitalist class. Writing at the time of Dickens, here’s Mikhail Bakunin from an article titled “The Capitalist System,” believed to be written sometime in the late 1840s:

“But the capitalist, the business owner, runs risks, they say, while the worker risks nothing. This is not true, because when seen from his side, all the disadvantages are on the part of the worker. The business owner can conduct his affairs poorly, he can be wiped out in a bad deal, or be a victim of a commercial crisis, or by an unforeseen catastrophe; in a word he can ruin himself. This is true. But does ruin mean from the bourgeois point of view to be reduced to the same level of misery as those who die of hunger, or to be forced among the ranks of the common laborers? This so rarely happens, that we might as well say never. Afterwards it is rare that the capitalist does not retain something, despite the appearance of ruin. Nowadays all bankruptcies are more or less fraudulent. But if absolutely nothing is saved, there are always family ties, and social relations, who, with help from the business skills learned which they pass to their children, permit them to get positions for themselves and their children in the higher ranks of labor, in management; to be a state functionary, to be an executive in a commercial or industrial business, to end up, although dependent, with an income superior to what they paid their former workers.”

Today, Bakunin is recognized as one of the fathers of anarchism, but he is also considered one of the most influential political and economic theorists of all time who offered several important contributions to socialist theory and challenged many of Marx’s most significant assumptions. And, with that, let’s fully bring our philosophers into the conversation to eavesdrop on the most important conversations in the development of socialism.

Chapter Seven: Marx And Mill.

“The materialist doctrine—that humans are the product of circumstances and education and that changed humans are thus the product of changed circumstances and education—forgets that circumstances are changed by humans and that the educator himself must be educated. It must therefore split society into two parts—of which one is elevated above society (for example in Robert Owen). The convergence of the changing of circumstances and of human action can only be understood and comprehended rationally as revolutionary practice.”

This excerpt from Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach in 1845 reflects the changing attitudes among the classes, altered by the circumstances of education and industrialization. As much as philosophers were imagining new social, political and economic structures, the newly formed working classes were changing, as well and agitating for change. It’s in this agitation that we find one of the most significant shifts among the great thinkers of the time. The commonality in their critiques is in many ways obvious. Where their paths diverge is in their beliefs about the future.

Turns out, the working class had its own ideas of where the capitalist system would go next.

To elucidate the emergence of socialist thought, let’s start with the oldest of the theorists who is least associated with socialism but provides a crucial bridge from some of our founding philosophers, most notably, Jeremy Bentham.

One of Bentham’s associates and mentees was a young John Stuart Mill. As I mentioned, Mill is sometimes excluded from the socialist conversation—he’s most associated with utilitarianism—but he’s a pure starting point for us because he paid little attention to our other philosophers while landing on very similar ideas.

James Mill was relatively poor, but had the good fortune of befriending one of England’s most prominent citizens, Jeremy Bentham. Mill himself possessed a keen mind and diligent work ethic and, together with his friend Bentham, they guided Mill’s prodigious son John Stuart, who would take up the mantle from Bentham to become one of Britain’s brightest intellectual lights.

Born in 1806, John Stuart Mill was treated from an early age to a radical and profound education, which included time in France at the age of 14, where he not only became proficient in French but mesmerized by French culture and politics. The forward thinking nature of Mill’s education included Bentham’s utilitarianism and David Ricardo’s synthesis of politics and economics. Over time, he would develop his own thoughts on the nature of capitalism and the developing industrial landscape and meld the teachings of his famous mentor and taskmaster father into his own unique brand of utilitarianism.

Mill pushed beyond the limited scope of philosophical morality to extend the concept of utility into all areas of life and governance from jurisprudence, democracy, worker’s rights and, most notably, women’s suffrage. You might have noticed, by the way, that our discussions thus far exclude female philosophers. That’s deliberate, because the fight for equal rights and suffrage was still in its infancy. As we’ll see in the next sections, some of the most fierce advocates for socialism and anarchism were women who linked worker’s rights and suffrage together in a profound way to advance the cause of feminism. So many consider Mill to be one of the earliest and most significant figures in the feminist movement, with one of his most well-known works titled The Subjugation of Women (1869) considered a cornerstone in the feminist literary canon.

Here’s Mill in his own words:

“The principle which regulates the existing social relations between the two sexes—the legal subordination of one sex to the other—is wrong in itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality, admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other.”

In his attitude toward women, we see Mill’s mind at work with respect to human rights and class distinctions. He would carry this over to the industrial sector when examining the plight of the laborer, giving over their time and labor to a selfish breed of capitalists. Remember that there were already thought experiments and actual experiments such as New Harmony that attempted to contrive situations that alleviated the brutal conditions of the workplace by placing control in the hands of the proletariat.