The Economics of Racism.

Bootstraps, Black Banks and Redlining.

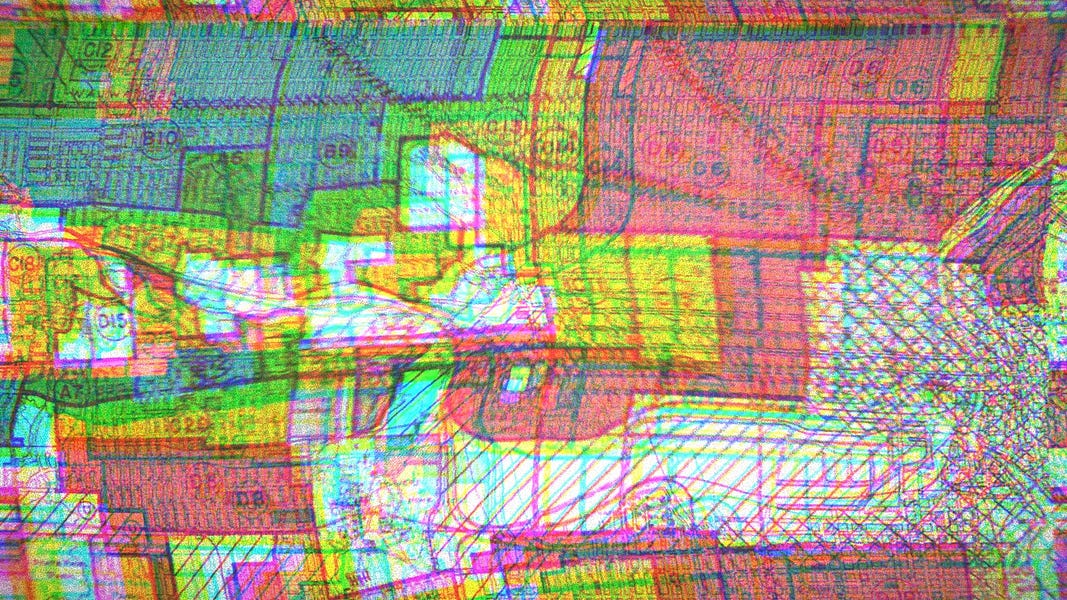

Image Description: Redlining in Milwaukee Map.

Image Description: Redlining in Milwaukee Map.

Unf*ckers, I’m back from vacation and sufficiently riled up and ready to go with another deep dive into socioeconomic issues that plague our little republic. We have a packed agenda today, which is what happens when I have a little too much time on my hands, sand in my toes and beer in m’belly.

My first working title for the show was ‘Digital Redlining.’ Then, I built on it, and the next working title was, ‘Holy Fuck We’re Racist.’ But that was too obvious, so I settled on ‘The Economics of Racism: Bootstraps, Black Banks and Redlining.’

There are a ton of sources for this essay that we’ll link in show notes—obvi—but the one that really took me apart and shifted the narrative of this essay is called The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap. It’s a couple of years old, but it filled in some really important gaps for me and altered my thinking on ethnic financing significantly. I’ll be pulling from it a lot, so please check it out if you haven’t already done so. We’ll put it up on our store in Bookshop.org.

Editorial note: This essay sources material that uses “Negro,” once the prevailing academic and journalistic term for the Black population. This instance will be used only when maintaining the integrity of the original sources and statements. Furthermore, the use of the term “Black” is intended to denote Black Americans from both African, Latin and Caribbean descent where it is culturally appropriate to refer to this as a group identifier.

“Systemic.” “Structural.” “Institutional.”

We opened the audio essay with a clip from 107-year old Viola Fletcher’s testimony this year, recounting the Tulsa Massacre of 1921. Ms. Fletcher lived through the Tulsa riot and read prepared testimony on the 100th anniversary. Living history that will frame our discussion.

The Tulsa Massacre and burning of what’s come to be known as “Black Wall Street” has been in the news this summer for a few reasons. It was featured in a dramatic episode of HBO’s The Watchmen, has been been the subject of several documentaries, and it’s the 100th anniversary of the incident. And it’s also been used to counter the new right wing obsession of Critical Race Theory because this rather momentous and horrifying event is rarely covered in school.

As someone who presents as a white man in this country, it’s astounding how much other white people are comfortable revealing in casual conversation. The old joke that every Black joke starts with a white person looking over their shoulder is entirely true, though these days it seems like openly racist dialogue is more accepted than ever.

So I’m going to play traitor to my perceived race up top here and explore some perceptions that are widely held among whites in America. Not that everyone isn’t familiar with them. I just want to put them out there so we can get busy dispelling some myths, as usual, and really talking about stuff that matters. The hard stuff. The tricky stuff.

So here you go:

-

“Every other immigrant group in this country was able to break out of the ‘ghetto’ within one generation. Why can’t Black people?”

-

“It’s easier in today’s society to get ahead as a Black person because they have all the advantages through Affirmative Action, whether it’s college or jobs.”

-

“Black people commit more crime and come from broken homes. They have to fix themselves, no one else can.”

-

“Slavery isn’t an excuse anymore. Clean slate.”

-

“One of their own became president, so they can’t complain anymore.”

-

“I worked my ass off to get here and they just look for handouts.”

And my favorite:

-

“They need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps.”

So admit it, white people. Even in the most polite company and even among those who consider themselves fairly open-minded, these conversations really happen. All the time.

On vacation, I finally picked my head up to watch life’s passing parade. Every pickup truck with flags attached to the bed and a ‘Fuck Your Feelings’ sticker that went by, every Trump 2024 sticker or MAGA hat brought me back to the subject of language and how our diminishing intellect and short attention spans have disabled the parts of our brains that think critically and question authority.

Make America Great Again. Trickle Down Economics. The Silent Majority.

Cut Taxes. Free Markets. Invisible Hand. Tax and Spend. Job Killers.

Lock Her Up. America First. Looting. Inner city.

Thugs. Illegal Immigrant. Radical Muslim.

Pull yourself up by your bootstraps. Even if you don’t own a pair of fucking boots.

And when we want to counter these dangerous and coded sentiments, we wind up using words like systemic, structural and institutional. You know what you mean. You’ve studied this shit. And so you use words with deep meaning to you that are too broad for others who can just as easily remember bumper sticker slogans.

To most, these are throwaway words. Language of the pompous and elite. Institutional poverty. Structural inequality. Systemic racism. What the fuck do these words even mean to someone working a 9–5 job, wondering if they can put their kid through college without six figure debt, or maybe how the hell they’re going to afford the prescription drug they were just denied for the 15th time by their insurance company? They’re not looking to do their homework, they’re just looking for someone to blame.

Black Wall Street

To understand the meaning behind structural, institutional and systemic, we’ll walk carefully through post-emancipation history to reveal why the economic challenges that have always and still face the Black community in the United States are entirely different than any other racial or ethnic group. We’ll start by revisiting Ms. Fletcher’s testimony and the burning of Black Wall Street.

Free Black people migrated to Tulsa, Oklahoma after the Civil War during the nation’s westward expansion. By 1910, the Black community made up 10% of the population of Tulsa and had created a thriving and booming economy, which included a financial district in Greenwood that was known then as “Negro Wall Street,” and updated recently to be referred to as Black Wall Street.

Black people in Tulsa during the ‘10s and ‘20s were some of the wealthiest members of the community. They had the highest priced and most opulent buildings, a thriving banking system and speculative activities in the region created a boomtown feel. Among countless setbacks for freed Black people in the United States during the Jim Crow era, Tulsa stood as a beacon of progress and hope for what the future could hold.

In May of 1921, all of that came to a crashing halt. On the claim that a Black man assaulted a white woman, despite no evidence or charges, the man was held in prison and a white mob quickly formed. As Mehrsa Baradaran writes in The Color of Money:

“The white mob set the city ablaze. By the time the destruction was over, 18,000 homes had been burned, 304 homes had been looted, 300 people—mostly Black—had died, with many more injured and $2 to $3 million in property damage had occurred, including the lavishly built Zion church, the heart of Black Greenwood.”

The wealth of Black Tulsa residents was wiped out in a single violent night. And as Ms. Fletcher would testify, it never returned. Not for her or her family. Not for any of them.

When the Civil War ended, Black people in the United States possessed a half of 1% of all the wealth in the country. Today, that figure is 1%.

What transpired between then and now is encapsulated by what happened in May of 1921. Not always on such a fiery and grand scale. Not always, though certainly quite often, to such a violent and immediate extent. But it happened consistently, over and over, decade by decade. Every inch of economic progress and mobility was met with systemic, institutional and structural barriers erected for the express purpose of suppressing the Black people of America.

It wasn’t only in the south, it was in the north and exported west during expansion. This wasn’t a southern thing. It was an American thing. As de Tocqueville wrote upon visiting America, “The prejudice of race appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.”

40 Acres. And a...mule?

40 Acres. And a mule, as the saying goes. (Also the name of Spike Lee’s production company.) This was the first broken economic promise in a long line of broken promises that continue to this day.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, President Lincoln acted on a gesture from a union general who apportioned conquered plantations and land in the westward expansion to freedmen, recently emancipated enslaved people. Freedmen were to be deeded 40 acres to build their lives. They were, after all, skilled agricultural laborers. (The mule thing is more legend, as there were stray mules after the war that were given as property to a number of freedmen.)

The period known as Reconstruction, when this and other promises were made, was brief. Nearly all of it was undone immediately by President Andrew Johnson, a devout racist. Southern separatists were all pardoned, and those who had their land confiscated had it returned. At this point, a series of new ordinances, followed by state laws and then federal laws, were passed to ensure that any post-war reparations and economic advantages were given exclusively to whites. Laws such as the Homestead Act that encouraged white settlers to move west, with southern states forbidding the sale of land to Black people.

So building wealth through land ownership was off the table. Black people were therefore forced to resume their labor activities, although this time they were part of the market and could command a wage, even if it was paltry compared to their white working counterparts. What to do with their money was another question entirely, as Black people had never banked before. So a new movement was sparked.

A movement that every single Black leader including Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois to Martin Luther King Jr., Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X and Jesse Jackson would promote. A movement that would be aided and promoted by multiple presidents, from Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon and even Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter.

If Black people were going to get ahead, they needed to “keep their money Black.”

Freedman's Savings Bank established by President Lincoln was the first attempt at creating a Black banking system and economy. It gathered pensions from deceased Black soldiers and encouraged freedmen from around the country to pool deposits there, and they did. Small businesses, farms, churches, individuals poured money into the bank and, within a decade, it had more than $75 million in deposits.

The crucial point here is that the bank was established as a savings bank, and not a lending institution. Honorable white trustees were placed in charge of the fast growing bank to safeguard it and help build wealth for southern Black people to build lives with their newfound freedom. Unfortunately, that’s not how wealth is built, and it’s not how banks make money. Banks make money on lending, not saving.

Over time, the bank’s leadership changed and new trustees began to gamble in speculative ventures and push toward expansion. And for a while, it looked like it was working. But remember, this was during the beginning of industrialization and capitalism. There were no bailouts. No FDIC. No guarantors.

Eventually, the speculative forces of the bank changed it into an investment bank to finance riskier and riskier endeavors, most notably railroad construction, and soon other banks began moving their garbage investments to the Freedman balance sheet. And then, along came the Panic of 1873, and everything started to unravel.

Even the great Frederick Douglass was appointed as head of the bank as a sign of strength. Of course, he knew next to nothing about banking, and it was indeed just a show. The white speculators had pilfered the bank’s assets and loaded it with bullshit paper.

By the next year, the bank was lost and along with it half of the accumulated Black wealth in the nation.

It would be years before Black Americans would trust the banking system again. And when they did, mistakes of the past would be repeated—pouring money into depository institutions, rather than advancing credit and making loans—and sadly, they continued to lose wealth time and time again.

The True Reformers Bank, once called the “Gibraltar of Negro Business,” was founded in 1888 and folded in 1910. The Alabama Penny Savings and Loan Company was founded in 1890 and failed in 1915 after a run on the bank. Nearly every Black bank throughout history was destined to fail. But why? And why did it happen even when we had Keynesian protections in place later in the Depression to prevent the loss of deposits? If banks are banks and money is money, why did Black banks fail while others succeeded?

This essay is not about the violent acts of open aggression promulgated by the Ku Klux Klan. It’s not about forced segregation or lynchings. It’s about the economics of racism. To show how systemic, institutional and structural the issues are, we’re going to do a decade-by-decade highlight reel to understand the inherent racism in economic policies that prevented a particular group of people in the United States from participating in any of the gains and prosperity that came from capitalism, industrialization and globalization.

Before we turn back the clock a century, recall from our Corporate (Ir)Responsibility essay, that one of the primary ways we accumulate wealth in this country is through inheritance and specifically wealth generated from the ownership of property. That’s the foundation of wealth and mobility to understand as we run through the last century together.

100 Years of Racist Policy

The 1910s

The country was still raw from the Civil War, and the south was steadily losing its economic edge to the north and the oil and gas and mining discoveries out west. States were increasingly devising laws and ordinances to prevent Black families from acquiring property, moving from Black neighborhoods, owning businesses or getting government work. From The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein:

“In 1910, Baltimore adopted an ordinance prohibiting African Americans from buying homes on blocks where whites were a majority and vice versa.”

The 1920s

The country was rocking. Roaring, actually. The stock market was flying high and speculators were getting very, very wealthy in all corners of the bursting American economy. White landowners were amassing enormous tracts of land and building cities with gusto. Unfortunately, Black families were specifically locked out of this newfound economic and physical mobility. Again, from The Color of Law:

“In 1926, Indianapolis adopted a regulation permitting African Americans to move to a white area only if a majority of its white residents gave their written consent. In Florida, a West Palm Beach racial zoning ordinance was adopted in 1929 and was maintained until 1960.”

These were just examples of zoning laws that precluded Black families from moving anywhere other than “the ghetto.” I selected these to demonstrate that these laws weren’t just southern. They were the law of the land. All of the land.

The 1930s

What goes up must come down.

We all know what happened next, as the nation and the world fell into the Great Depression. We’ll spend more time in the ‘30s, because the nation’s policy response during the Depression would devastate the Black community long after the rest of the nation recovered during and after World War Two.

From the turn of the 20th Century through the crash and subsequent Depression, Black banks actually began to flourish despite the barriers put in place for land acquisition and mobility. Keep money Black was the mantra, and that’s exactly what happened. What was made in the Black community remained there, both a blessing and, ultimately, a curse.

For example, John D. Rockefeller established the Dunbar Bank to “help the Negro help himself” by taking deposits in New York. But the bank was designed to be risk averse and so instead of investing in real estate and other business or home loans, it put the deposits into treasuries, you know, for safekeeping like any good white paternalistic overseer would do. Rockefeller promised that half of the shares of the bank would go to the community, but instead he just held onto all of it. The one big project it managed was the construction of a residential cooperative where Black people could earn into ownership of real estate.

But Rockefeller tired of the initiative during the Depression, foreclosed on the cooperative and shuttered the bank in 1938. From The Color of Money:

“From 1900 until 1934, some 130 Black banks came into being, 88 of which were formed between 1900 and 1928…The titans of Black finance in the north were both located in Chicago: The Binga State Bank and the Douglass National Bank. At their peak in 1928, they controlled almost one-third of the combined resources of all Black banks in the country…Binga’s bank was the first in Chicago to fail during the Great Depression.”

The reason Binga failed when some others didn’t is because the clearinghouse it belonged to rejected his request for an extension of credit during the initial shock of the crash. From The Color of Law:

“All the other banks that belonged to this clearinghouse were given aid and survived the Great Depression…On July 31, 1930, Illinois bank auditors closed Binga’s bank and his depositors lost most of their savings.”

The Douglass National Bank, which had $2 million in assets prior to the crash, was the only Black bank that was chartered as a national bank. It too failed after receiving no support.

Aside from Rockefeller’s soon-to-fail Dunbar Bank, New York had almost no Black banks because New York’s regulators continually prevented and blocked Black bank charter applications. In fact, the Chelsea Bank, a white competitor downtown, was responsible for preventing most of the charters because it took most of Harlem’s deposits and yet made no loans back into the community. So, through the 1920s, Harlem’s wealth was used to finance white projects elsewhere in the city.

Beyond banking, this was the era of massive financial and economic reform as Franklin Roosevelt threw everything against the wall to salvage the American economy.

One of the most prominent and enduring examples of systemic, structural and institutional racism came from a 1933 act that created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to rescue homeowners from defaulting on their mortgages. The idea was to buy the troubled mortgages and re-issue them with longer and more favorable terms to prevent people from being thrown out on the street. In order to determine which houses were in need of saving, the HOLC hired local realtors to appraise properties.

So they created color coded maps for every city in the nation with green lines denoting the good areas and red lines denoting the bad. And we all know what they meant by “bad.” Thus, the term redlining was born. Something we’ll return to near the close of the essay.

Another of the reforms was the introduction of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934. The FHA’s 1939 Underwriting Manual explicitly prohibited lending in neighborhoods that were “changing” in racial composition. Naturally, the FHA utilized the maps drawn by agents of the HOLC.

Another protection put in place to prevent banks from failing in the future was Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) designed to insure banks against potential runs. This was especially important to banks that had high exposure as savings and depository institutions that did few property and commercial loans.

This remains one of the most important protections in our system today, and it was actually lobbied for by the southern states who also demanded Glass-Steagall prohibit conglomeration, mergers or even bank branching across state lines. The fear was that northern banks, stronger by nature, would eventually take over the country and push out the states. In order to get FDIC chartered, however, banks had to hold a minimum amount of capital and submit to routine examinations.

The rules were designed in such a way that chartering was done on a state level and thresholds were set that deliberately created an excuse for the FDIC to deny Black banks entry. This is part of a broader understanding of how the country has been able to institutionalize policies that negatively affect Black Americans. State’s rights. Throughout our history, the concept of “State’s Rights,” one of the central debates of our very founding, has been a policy stand in for racism.

This left the country in a situation for decades where every subsequent reform pushed Black banks further into a corner. They had to stay within their community boundaries, had difficulty even getting state charters, were then denied access to the FDIC for lack of charters and capital requirements and then excluded from FHA provisions deliberately so lending at scale wasn’t an option.

The 1940s

Even in the cities, Black people would be blocked at every turn. For example, in 1942, Metropolitan Life embarked on a project to build a 9,000 unit Stuyvesant Town housing complex on the east side of Manhattan, following up on another successful development in the city from 1938. To make way for “StuyTown,” the city cleared 18 city blocks and transferred the area to MetLife, along with a multi-decade tax abatement.

The project was designated for whites only, despite this now being illegal under federal law. By the time the company was compelled to change their policy, every apartment in the development was filled.

This was during a time when the nation was at war and more than a million Black Americans fought abroad for U.S. interests. Of course, when they returned home, little had changed. But hope was on the horizon. One of Roosevelt’s last major legislative accomplishments was the passage of the G.I. Bill, which would assist returning veterans in myriad ways, including a mortgage guarantee. For the 1.2 million returning Black veterans, this finally offered the promise of home ownership outside of American ghettos.

While the bill did not specifically exclude Black Americans from securing its benefits, the filibuster did in a roundabout way. Southern racists filibustered the bill until a provision was included that allowed states to administer benefits such as mortgages. Once the federal government lost control of the administration of benefits, the bill was basically D.O.A. for Black Americans who were turned away almost universally by states and municipalities.

As Adam Jentleson writes in Kill Switch, which details the racist use of the filibuster in the Senate:

“In the eighty-seven years between the end of Reconstruction and 1964, the only bills that were stopped by filibusters were civil rights bills.”

Jentelson rightly notes that southern Democrats ran circles around well intentioned northerners through use of the filibuster especially during the New Deal era because, for the most part, they were aligned with Roosevelt. They were in favor of redistributing wealth, just only to white people.

The 1950s

By 1950, the FHA and VA together were insuring half of all new mortgages nationwide. The rest of white American homeowners were able to secure more conventional loans. As for Black people, well, there was another option. From The Color of Money:

“For scores of developments across the nation, the plans reviewed by the FHA included the approved construction materials, the design specifications, the proposed sale price, the neighborhood’s zoning restrictions, and a commitment not to sell to African Americans.”

With half of the home loans being issued by agencies that excluded Black participation, a new market sprung up to fill the void. After all, everyone was working in America during the time, which meant that Black people were just as employed as whites. The only difference was the only option they had to store their earnings and accumulate wealth was through small interest on savings. Because they were working and desirous of home ownership like everyone else, the new market that came along was something called contract selling.

These were basically leases with options to buy that had punitive interest rates and penalties for late payments as extreme as total loss. By the ‘50s, 85% of the homes sold in Chicago to Black families were sold on such contracts.

With abundant employment, the seeds of wealth appreciation through home ownership and a booming economy, white America was sitting pretty, and things were about to get even better with access to greater purchasing power. Well, for white men at least.

Credit cards.

The shift from installment payments to revolving credit lines was a revolution that cannot be ignored. It freed up capital and increased the velocity of spending like never before. The only people who weren’t using credit to finance their lives by the end of the 1950s were either really rich or Black. Rich, because they didn’t need to. Black, because they weren’t allowed to.

The 1960s

In 1962, with federal urban renewal funds, Detroit began to demolish Black neighborhoods. The first project cleared land for expansion of a Chrysler automobile manufacturing plant. Then, federal dollars were used to raze more homes to make way for the Chrysler Expressway (I-75) leading to the plant. In advance, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights had warned the expressway would displace about 4,000 families, 87% of whom were Black.

In Camden, New Jersey, an interstate highway destroyed some 3,000 low-income housing units from 1963–1967.

Believe it or not, in the late 1960s, Nixon was welcomed with pretty generous Black support initially, despite the distrust he personally engendered among Black communities. Nixon was nothing if not shrewd, and he began to speak the language of what we now know was the so-called Southern Strategy. (Thank you Lee Atwater for explaining to the world what this meant.) Shift the conversation away from blatantly racist tactics and fear mongering and leverage the coded language of economic dislocation and inherent racism.

But for many in the Black community, this was exactly the pivot they were looking for. On the heels of Dr. King’s assassination and the brief victories of the Civil Rights Movement, Black leaders were looking for a way to build on their legislative capital and create economic capital. As far as they were concerned, the more the government left them the fuck alone, the better.

In practice, Nixon did indeed leave them alone, as he steadily began to walk back many of Johnson’s Great Society programs. Clever little dick that he was, he made this look magnanimous by shifting the strategy to support Black businesses and banking, but mostly in rhetorical and performative fashion.

For example, in 1969, he created the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE) within the Department of Commerce. The OMBE was not allocated any direct funds, but was instructed to seek private business contributions and help from other federal agencies. It was given responsibility for “advising,” “encouraging,” “mobilizing,” “evaluating,” “collecting information,” and “coordinating activities.” It told Horatio Alger-like stories about Black business people and little else.

Nixon’s Equal Employment Opportunity Office was created to foster employment, but it was a voluntary program. So no one actually joined in, but hey, it was great PR for big business.

Perhaps the most honest government report ever issued was the Kerner Report. I’m going to leave the rest of the ‘60s to this report, commissioned by LBJ and headed by Illinois Governor, Otto Kerner. From the Kerner Report:

“From 1950 to 1966, 77.8 percent of the white population increase of 35.6 million took place in the suburbs. Central cities received only 2.5 percent of this total white increase. Since 1960, white central-city population has actually declined by 1.3 million. As a result, central cities are steadily becoming more heavily Negro, while the urban fringes around them remain almost entirely white.

“As the whites were absorbed by the larger society, many left their predominantly ethnic neighborhoods and moved to outlying areas to obtain newer housing and better schools. Some scattered randomly over the suburban area. Others established new ethnic clusters in the suburbs, but even these rarely contained solely members of a single ethnic group. As a result, most middle-class neighborhoods—both in the suburbs and within central cities—have no distinctive ethnic character, except that they are white.

“Nowhere has the expansion of America’s urban Negro population followed this pattern of dispersal. Thousands of Negro families have attained incomes, living standards, and cultural levels matching or surpassing those of whites who have “upgraded” themselves from distinctly ethnic neighborhoods. Yet most Negro families have remained within predominantly Negro neighborhoods, primarily because they have been effectively excluded from white residential areas.”

So by the end of the ‘60s, despite the gains of the Civil Rights Movement and just as it happened after Reconstruction, Black people in America were relegated to ghettos, excluded from participating in the most prosperous decades in human history, paying more for crappier homes, buying things on installment instead of credit and saving very little.

The 1970s

Nixon’s OMBE launched an investment initiative to extend credit to minority businesses in 1970. The fund was bankrupt within the year.

The 1974 Fair Credit Reporting Act officially put an end to racial and gender discrimination by credit card companies. While it worked for women, who were basically locked out of credit cards until this point, the lenders skirted the regulations for ethnic minorities by simply carving out certain zip codes. Hey, free market. Right, Milton? You fucking pariah.

Free market ideals begin to take root with people like Alan Greenspan, who wrote that capitalism was under attack by Black militants and said, “The charge of exploitation in the sense of value being extracted from the Negroes without their consent for the profit of the whites is clearly false.” Greenspan had to say this, otherwise the entire premise of free markets and invisible hands would come crashing down in the face of the biggest market force in the U.S. Racism.

“By 1971, the SBA had allocated $66 million in federal contracts to minority firms One-tenth of 1 percent of the $76 billion in total federal government contracts that year…Multiple studies revealed that 20 percent of these set-asides had gone to white-owned firms.”

The 1980s

Welfare Queens. Tax Cuts. Trickle Down. By the mid-‘80s, middle class Black families had one fifth the wealth of white families and half of Black children were in poverty. And yet, the war on welfare began in earnest, with Reagan determined to take back any and every subsidy or program that supported poor families.

For the rest of the Reagan story, check out our essay titled “The Beatification of Ronald Reagan.” And, fuck that guy. Seriously. #FRR

The 1990s

In 1991, the Environmental Protection Agency issued a report confirming that a disproportionate number of toxic waste facilities were found in Black communities nationwide. Another 1991 study, this one by the Federal Reserve, found widespread discrimination in home mortgages, with Black people being disproportionately sold subprime loans even if they qualified for conventional ones.

This was the era that saw the explosion of subprime mortgages. Wall Street had already figured out that they could bundle mortgages into pools of investments called mortgage backed securities. An incredible innovation that led to a massive spike in home loan originations because the packages spread the liability and were remarkably stable. So stable that Wall Street created something called a collateralized debt obligation (CDO), that gambled on these packages even further by allowing them to be leveraged.

But the whole thing was predicated on an influx of new mortgages, so the mortgage industry once again found its prey in the Black communities and created the subprime lending market. We all know now how that story ended. Even Black people who qualified for conventional loans were pushed toward subprime loans in a coordinated effort by mortgage brokers who didn’t have to worry about holding the loans on their balance sheets.

Therefore, they needed to make more money on origination fees and higher, punitive interest rates so they carried more value when they sold them. Seriously, what could possibly go wrong?

And to really put a fine point on the ‘90s, go back to our Mass Incarceration essay, which details the rise of incarcerated Black men and women in the United States at the hands of the Clinton administration. Or read The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander. Millions of Black men and women were taken off the streets and stripped of their ability to participate in either our democracy or the modern economy for low level, non-violent crimes that ensured that new generations of Black Americans would once again start from scratch with no inherited wealth or structure to stand on.

The 2000s–Today

And so our chickens came home to roost. We’ve covered a great deal of this already, Unf*ckers. Dot com bubble bursts with a brief recession and 9/11, then Dubya pours on the deficits, keeps those tax cuts rolling, builds on the war economy and lets Wall Street do whatever the fuck it wants until the wheels come off the car doing 120 down I-95.

And once again, like nearly every prior decade, the financial crisis wiped out 53% of total Black wealth.

The protracted recovery stymied by neoliberal caution and a Republican congress determined to cut our first Black president off at the knees at every fucking turn meant that the Black community would recover more slowly. But we have a Black president at least, right? He made it, so you can too! Except that this Black president was the son of a mixed race marriage whose white grandparents studied on the G.I. Bill, bought a house through the FHA and moved to Hawaii.

And so we’re left in a situation where Black families have an average net wealth of $11,000 compared to a white family’s average of $141,900. Or as Pew puts it, “white families have thirteen times more wealth than Black families.”

And, of course, the most recent statistics are coming in from Pew, the St. Louis Fed, Brookings and others that depict the obvious from the pandemic. That it was disproportionately brutal on Black and Latino communities.

Whew. There you go. A hundred years of fuckery. A hundred years of economic brutality delivered to one group and one group only. And these were only highlights.

Economic Corollaries of Racist Policy

There are so many corollaries to this kind of mass scale, coordinated economic dislocation. We didn’t even touch on gentrification.

When an area gets hot, whites will use their economic power to purchase properties, change zoning laws, “block-bust,” condemn properties, whatever they want in order to “improve” a neighborhood. Which is to say, gentrify it.

Then there are schools and education. The education gap between Black and white people in this country is staggering, and it all stems from the state’s rights notion that local municipalities should control tax dollars for education rather than having an equitable distribution of dollars at a state or federal level. The result is the disparity in funding between white neighborhoods that enjoyed more than a century of economic development and opportunity and Black neighborhoods that experienced the opposite.

Think about Milton Friedman’s thoughts on why Black people were, “less educated” than whites in the U.S. He said it was due to a lack of school choice. Friedman’s contention that the way the districts were funded by local tax dollars necessarily held down Black districts because they were poorer was correct. But his solution was that we should have school choice and vouchers.

Just stop for a second and think about how clever this argument is if you’re willing to check your fucking brain at the door and just accept it. To Milton, and all of his policy acolytes that followed his every word for decades thereafter, this was the beginning and end of the story. But they never had the courage or desire to open just one more fucking door and ask why Black people were all gathered together in these districts and had less wealth.

If you open that one door, and you find a torrent of explanations like the ones we went through today. Black people were discouraged from moving into white neighborhoods by realtors, mortgage companies and homeowner’s associations. Or they simply didn’t qualify for the home ownership programs made available to white populations, even if there was income parity between them.

And if they somehow overcame these obstacles, they were oftentimes met with violence from their would-be neighbors. Garbage thrown on their lawns. Crosses burned on them, even in the north. Ridicule and exclusion from community gatherings and activities. To Friedman and other “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” economists, these social factors were inconsequential because they frustrated the political and social realities of their pristine economic models.

Think about something as basic as the price of food. In the Kerner Report, they noted that on the whole, food prices were relatively stable regardless of neighborhoods, income distribution or class. However, they opened another door, went a step further and looked at the purchasing habits.

Because densely populated areas were generally what we would now term “food deserts,” meaning they didn’t have large scale grocery stores, most community members were forced to shop as smaller local stores. First off, because they typically didn’t have access to automobiles because they didn’t have the credit to purchase them. So there’s that.

Further, because they had smaller incomes and less savings, they shopped more often and in smaller quantities. And the smaller the quantity, the smaller the discount. And because they were independent stores, the operators themselves typically had to mark up these smaller quantity items because they couldn’t afford the purchasing power advantage the larger chains had.

Just keep opening doors, Unf*ckers, and eventually you’ll get to the root cellar.

Digital Redlining

Then there’s the modern version of redlining that has crossed over to the digital realm. Digital redlining is thankfully an issue that is receiving some policy attention but it remains somewhat of a hidden issue that further masks the structural issues Black people have to accessing the economic engine of capitalism.

During the pandemic, an iconic photo was taken of young girls doing their homework in the parking lot of a Taco Bell in California. Why? Because connectivity wasn’t robust or fast enough in their home communities to keep up in school. Why? Because redlining never ended, and communities of color have been conveniently passed over by companies responsible for laying fiber and enhancing connectivity.

The pandemic, for better or worse, brought the disparity to light.

Uncle Milton and his colleagues actually bear some direct responsibility for the gaps in digital access, even though the internet wasn’t a thing. Recall from our F*ck Milton essay that the Chicago school economist Ronald Coase was the godfather of deregulatory thought when it came to auctioning off spectrum. Instead of it being an equitable distribution system, Coase argued that spectrum should be placed in private hands to monied bidders. This was the basis of the deregulatory period from the ‘90s on, that placed spectrum in private hands instead of treating it as a public utility that should represent the communities they served.

So because the FCC took steps to sell access instead of mandating it and regulating it as they did when phone lines were distributed across the nation irrespective of density or ability to pay, the internet was allowed to grow and expand through private hands without threat of regulation. Now that our economy requires high speed access to be competitive, the absence of regulators has created a situation where wealthy end users are getting fiber, but predominantly low-income users are not being transitioned off legacy infrastructure.

The result being “digital redlining” of broadband, where wealthy broadband users are getting the benefits of cheaper and faster Internet access through fiber, and low-income broadband users are being left behind with more expensive slow access by that same carrier.

A joint study last year from the Alliance for Excellent Education, National Indian Education Association, National Urban League and UnidosUS found that 34% of American Indian/Alaska Native families and about 31% each of Black and Latino families lack access to high-speed home internet, versus 21% of white families.

Microsoft, which tracks how quickly people download its software and security updates, estimates 120.4 million people, or more than a third of the U.S. population, don’t use the internet at broadband speeds. Adding insult to American exceptionalism, compared to the rest of the developed world, the Open Technology Institute has found that the United States has on average the most expensive, slowest Internet among modern economies.

The fix for this is pretty simple, but there is absolutely zero political will on either side of the aisle to piss off the cable and telecom giants. And I’m not talking about Biden’s infrastructure plan, I’m talking about a regulatory change. The FCC could have reclassified broadband as a telecommunications service, which would have placed them under the old telephone rules and required the companies to provide access no matter the profit picture.

Oh, but we can’t hurt the free market! What about the poor companies that will lose money connecting poor and marginalized people to the Internet that would make them competitive in the marketplace?

Which companies are we talking about?

- Verizon, who booked a $41 billion profit in 2020?

- Comcast, with $10 billion in profit in 2020?

- AT&T, who booked $27.5 billion in free cash flow last year?

Remind me again which one needs our help?

I don’t care where you are on the political spectrum, every politician in America takes money from these organizations; Bernie, Joe, Trump. They all take in telecom money because their racism and anti-poverty actions aren’t as obvious as drawing lines on maps and saying “don’t give money to these people.”

“There are significant differences in what happened then [with mortgage redlining] and what’s happening now,” said Hernan Galperin, an associate professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and one of the study’s authors. “But you could argue that ultimately the result is the same.”

And what about those companies that rely on the digital infrastructure of the nation? You’ll never fucking believe it. An investigative report from Bloomberg News revealed a shocking—or not—racial disparity in where next day Amazon prime delivery was available. The maps were like a fucking bad joke. Four of the five boroughs in NYC had Prime. The only one excluded? The Bronx.

In Boston, literally every single neighborhood had Prime availability except for Roxbury, the predominantly Black neighborhood smack dab in the middle. Like a donut hole carved out.

Chicago? Everywhere but the South Side.

And so on, across the country.

Economic Appropriation

There are other aspects of economic oppression that aren’t as obvious. Think about the co-opting of culture that has occurred. From jazz and blues musicians having their work pilfered with no credit and an entire industry growing around this appropriation. (Ask Led Zeppelin where they got many of their songs.) Or the fleecing of Motown artists by white record labels and executives. “Blaxploitation” films. The lack of Black owners in sports dominated by Black athletes. This trend continues today, as highlighted by the recent #BlackTikTokStrike where Black creators staged a walkout on the platform.

One of the sparks for this performance strike might seem meaningless to most people who think TikTok is just a waste of time, but the amount of money generated on this platform for artists who know how to leverage it to promote their music, choreography, comedy and more is astounding.

The spark was an appearance on Jimmy Fallon, where influencer Addison Rae performed a number of viral dances that were choreographed by Black dancers without credit. Compare Rae’s $5 million in compensation in 2020 from TikTok to one of the Black choreographers named Jalaiah Harmon, who made $38,000 in the same period. This might not seem like a big deal to most, but it demonstrates how widespread and resilient the barriers to monetization are for Black creators.

When he’s not winning awards for podcasting with News Beat or banging his head against his monitor trying to edit Unf*cking the Republic, Manny Faces is a Hip-Hop journalist and scholar who has lectured all across North America about the business of Hip-Hop, appropriation and the intersection of Hip-Hop, politics and economics. Very few people can speak to the business side of the industry as Manny:

There’s a ton behind the concept of co-opting material and theft of compensation in the Black creator community that, as you point out, has been happening since white people ripped off the blues. But there’s also the concept of “giving back to the community.” With the rise of the Hip-Hop mogul over the years, a lot of talk has revolved around owning not only the work but the means of production, distribution, merchandising, etc. We’ve seen this from the likes of Russell Simmons, Master P, and Puff Daddy aka P Diddy aka Puffy aka Sean Combs aka Diddy or current aka Sean Love Combs. Yes. Really.

We’ve seen folks like Jay-Z move past record label ownership, proving himself not only a shrewd and successful businessman—but a business, man.

And on the surface, a stake in Tidal streaming and RocNation, or Combs and his Revolt TV, might allow for some uplifting of the communities from whence these superstars came.

But does it go far enough to help uplift the Black community as a whole? After all, Simmons owned and operated influential, leverage-building companies Def Jam Records and Phat Farm apparel… Until he sold them. His foray into the financial market, the RushCard, a prepaid debit card, was not only fined millions for operational issues, but heavily criticized as nothing more than a money grab, not the credit-building, financial literacy tool for Black folks it was presented as. Again, it’s notable that Simmons, who has been MIA from the public eye after facing damning sexual assault claims, sold RushCard for $147 million in 2017.

Jay-Z was applauded for his partial ownership of the Brooklyn Nets and Barclays Center. On the flip side, he has faced criticism for what those endeavors did to gentrify downtown Brooklyn. Overall, his string of profitable business ventures have done very well for him personally, and while he has used his influence in areas such as social justice, there really isn’t much impact to point to when it comes to uplifting the overall financial wellbeing of Black America.

Now, Killer Mike is very vocal about this. The #BuyBlack #BankBlack advocate helped start Black and brown-owned financial institution Greenwood that is squarely focused on that “keep Black dollars in the Black community” mantra. But while it presents as a bank, and has welcomed tens-of-millions of dollars in deposits, it’s not a bank. It’s not FDIC insured. And based on this entire essay, I’m really curious if it’s something that is as revolutionary and, frankly, as helpful to the cause as it’s being presented.

Maybe the one we should be paying attention to is Nas. Though most would know him as a respected, veteran artist, he is in fact, also a highly successful venture capitalist. Queensbridge Venture Partners, which Nas co-founded in 2014, has helped fund iconic startups including Lyft, Casper, Dropbox, and Ring. This might be the kind of thinking that is really needed, to help pave the way for other Black artists to look beyond just monetizing creativity in traditional ways, or dabbling in questionable financial services. To look toward greater participation in established capital markets, to finally have the leverage needed to escape any efforts that could be made to shut them down, and to pass this wisdom around, in the uniquely effective ways that only Hip-Hop’s masters of ceremonies can.

And that ties into our conclusion, coming up shortly, and one of the central themes of the research we’ve done for today’s show that quite frankly turned my head 180 degrees on the subject of Black money and Black finance.

Hard Truths

Time to answer the questions we posed up top.

“Every other immigrant group in this country was able to break out of the ‘ghetto’ within one generation. Why can’t Black people?”

Because they were prohibited entry to communities outside the ghetto. First, through violence, then legislation and policy. It was death by acronym. The FHA, FDIC, G.I. Bill, VA, HOLC all created and maintained policies to prevent Black people from obtaining mortgages and accessing the mechanisms of wealth building and preservation. While the policies may have been eradicated, the practices remain to this day.

“It’s easier in today’s society to get ahead as a Black person because they have all the advantages through Affirmative Action, whether it’s college or jobs.”

The numbers are incorrect, to begin. The only racial group with larger education participation than their population ratio in America is Asian. The population that remains underrepresented in higher education, compared to their proportion of the population, is Black people. Because the Black community has less accumulated and inherited wealth and has been barred from participating in the broader economy outside of their community solely on the basis of their skin color, few even have the means to access higher education. And when they do, they are charged higher rates on loans.

“Black people commit more crime and come from broken homes. They have to fix themselves, no one else can.”

Black people commit crime at the same proportion as all other races, but are more likely to be targeted and convicted of crimes than white people and given longer, harsher sentences. They also lack the economic means to procure proper representation. The real conversation should be about class, as poor people are victims and perpetrators of more crime than rich people. It’s not a race thing, it’s a money thing.

“Slavery isn’t an excuse anymore. Clean slate.”

A clean slate would require complete access to the housing market, a change in the way schools are funded, equitable access to broadband, low interest loans and revolving credit. No historically marginalized group has broken the cycle of poverty without access to these mechanisms, and no group outside of the Black community has been systematically, legislatively, violently and purposefully excluded from doing so. None.

“One of their own became president, so they can’t complain anymore.”

President Obama is the ultimate Horatio Alger story, but even his is a story of access through his white grandparents, who availed themselves of the mechanisms of wealth and access established in the New Deal.

“I worked my ass off to get here, and they just look for handouts.”

White people receive more handouts than Black people and, throughout history, have built great wealth through government programs and subsidies denied to Black people through legislation, official and unofficial policies, and behavior. Historically, when given the same opportunity as whites, Black people have demonstrated an equal ability to acquire wealth and build communities. The difference is that white people actively burned them to the ground and, in the case of Tulsa, quite literally so.

“They need to pull themselves up by their bootstraps.”

As the good Dr. King said, “It’s alright to tell a man to lift himself by his own bootstraps, but it is a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.”

What to do?

This leads me to a conclusion that is half obvious and half not. Since the Civil War, Black people in America have enjoyed access to social and economic benefits for about ten years total; the handful of years post-Emancipation and prior to Jim Crow laws and the period between the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and the election of Richard Nixon.

That’s about it. The rest of U.S. history belongs to white society.

Black leaders throughout history got it exactly wrong on matters of finance and banking. This was the hardest part for me to wrap my head around. Keeping money Black and building Black banks inside Black communities was a trap that guaranteed credit and income appreciation were impossible and banks would remain undercapitalized and fragile. The answer is more Nas than Jay-Z.

To participate in the broader economy, the Black community has to go beyond its own community to gain access to capital and credit. It must be allowed to legally and socially retain its cultural heritage while assimilating its finances into the broader system so it’s harder for the white economic establishment and political leaders to isolate it and crush it through violence, policy or both.

The one commonality between the post Emancipation and post Civil Rights movement is that these brief periods were forged in revolution and upheaval. War and riots. The only reasonable conclusion one can draw from this is that the only way for the Black community to move forward is to revolt. It’s the only thing that appears to work, even though results are temporary. But no one wants that, least of all the Black community.

So the real answer is...

Reparations.

Every ten years, we wipe out the wealth of half of the U.S. population, thanks to Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan. We’ve established this as a building block to this essay. That is our quasi-capitalist, free market model that resulted in oligarchy. Unf*ckers have this part down.

So if we now add to the equation that Black people have been systematically denied access to wealth accumulation to begin with, then the combination of free market neoliberalism and racism ensures that Black mobility in the United States will forever be out of reach. The equation in the United States is pretty basic.

Free Market Neoliberalism + Systemic Racism = Economic Cataclysm

This is where our MMT and Culture Cancel essays now come into play. We know we can pay for low interest rate debt programs.

-

We should establish a fund that does exactly that, but solely for Black and Native Americans and for the purpose of acquiring property.

-

There should be an insurance guarantee corporation that undergirds a revolving credit market for discretionary purposes that are available only to Black and Native people.

-

Federal school loans should be refinanced at the lowest rate possible for all Americans, regardless of income.

-

Child credit payments should never revert back to tax credits. They should remain as payments.

-

The FCC should reclassify telecom companies to compel them to lay fiber in every community.

-

Amazon should go fuck itself.

Absent such reforms, change is impossible. Absent these reforms, revolution will come.

Fuck your bumper sticker ideology. Read a goddamn book. Reparations now or revolution later.

Here endeth the lesson.

Max is a political commentator and essayist who focuses on the intersection of American socioeconomic theory and politics in the modern era. He is the publisher of UNFTR Media and host of the popular Unf*cking the Republic® podcast and YouTube channel. Prior to founding UNFTR, Max spent fifteen years as a publisher and columnist in the alternative newsweekly industry and a decade in terrestrial radio. Max is also a regular contributor to the MeidasTouch Network where he covers the U.S. economy.